“Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine” are the famous opening words sung by the godmother of punk rock, Patti Smith, on her debut album, Horses. On Wednesday, April 11, 2013, the same Patti Smith—a self-proclaimed “non-Catholic who loves catholic things”—was escorted by the Swiss Guard to the front row of Pope Francis’s Wednesday audience. The Pope greeted her with smiles and words, heavily documented by the Vatican photographers. Most recently, the Holy Father invited Ms. Smith (along with Sr. Cristina Scuccia) to take part in a Christmas concert this month. What does the leader of the Catholic Church have to say to an apostate like Patti Smith? Everything.

This image describes one of the most formidable challenges that the Church must confront, a secularism that engenders apostasy. Christianity proclaims Jesus Christ, who gave his life in ransom for many, died, and rose on the third day. To reject this message is to refuse the gift of salvation offered to us. The rampant rejection of the Christian message is an issue all-too-often tethered to the personal. I can recall my mother howling along to Patti Smith in her room, stomping around, stoned out of her skull, trying to scream away her demons. Due to both its intense and delicate nature, both pastorally and theologically, preaching salvation requires that the very heights of theology meet the pastoral trenches, a procedure that demands the precision of a surgeon’s knife.

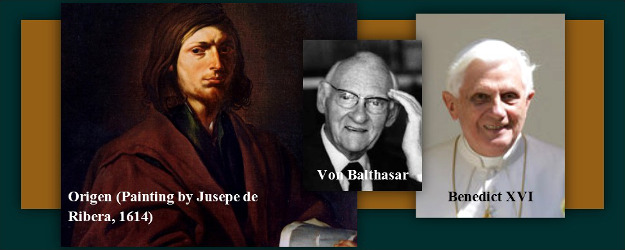

One theological possibility to remedy this pastoral situation is the apokatastasis, or universal salvation. At least in the Christian Tradition, its principal propagator is considered to be Origen of Alexandria. He, along with his writings, were condemned at the Fifth Ecumenical Council. Though condemned, the apokatastasis pops up elsewhere at different points in the Tradition, such as in Gregory of Nyssa and the writings of various mystics, though not in the mainstream. It has made its way into the 20th century, particularly in the writings of theologians such as Hans Urs von Balthasar, most famously in his work, Dare We Hope? It is my intention to demonstrate how Origen’s eschatology, grounded in the Scriptures, can fit—with some nuance—with an orthodox patristic vision of the Old Testament. Second, I would like to demonstrate the weakness and equivocation of von Balthasar’s argumentation for his position in Dare we Hope? Third, I would like to propose hope for salvation grounded in Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical Spe salvi.

Origen at the Origins of Analogy

Origen’s platonism has been interpreted as something like asbestos—it insulates well his theological system, but the results are cancerous. There is perhaps no more vicious critic than St. Jerome on this matter, who in a litany of complaints about the particulars of Origen’s thought, writes: “In speaking thus, does not most clearly follow the error of the heathen and foist upon the simple faith of Christians the ravings of Philosophy?”1 Hence, at the Fifth Ecumenical Council, Origen’s purported theory of the apokatastasis was condemned along with his theory of the transmigration of souls.2 While his contemporaries may have taken him for a platonist, reflections in recent scholarship have attempted to show him to be primarily a Scripture scholar.3 In the case of Origen’s eschatology, his vision of the apokatastasis is rooted in the scriptural, springing from the Pauline imperative that “Christ must reign, till he hath put all his enemies under his feet, that all things must be made subject to him,”4 or later in an eschatological interpretation of Jesus’ prayer ut unum sint in the farewell discourse of John.5 More fundamentally, however, Origen finds reason for the apokatastasis through an exegetical claim about Genesis: “Let us, I say, from such an end as this, contemplate the beginning of things. For the end is always like the beginning.”6 The “contemplation of the beginning” can be interpreted, as Origen’s opponents did, as one of the unfortunate intrusions of Hellenism in his thought. On the other hand, it is not foreign to Origen—nor to the Christian tradition for that matter—to read the Old Testament, and particularly the creation narratives, as a predictive document. Thus, “contemplating the beginning” can be construed as an exercise worthy of, and common to, Christian theology. For Origen, the announcement, “He made him in the image of God,” suggests “nothing else but this, that man received the honor of God’s image in the first creation, whereas the perfection of God’s likeness was reserved for him at the consummation.”7 Consequently, Origen’s understanding of the Genesis account has less to do with the origin of this world, than its future. In this sense, Genesis leans forward and points to what is to come. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger also shares a similar understanding of creation: “God created the universe in order to be able to become a human being and pour out his love upon us and to invite us to love Him in return.”8

Coming back to Origen’s statement, “For the end is always like the beginning,” the operative word “like” can serve to direct us, from a shallow reading that considers this an example of Hellenic eternal return, to the beginning of what later in the Tradition is called “analogy.” Considering Origen’s statement in an analogous way may help to avoid some of the pitfalls his interlocutors wish to oppose. To sum up, Origen’s account of creation is analogous to his vision of the eschaton, insofar as both are times where all is subject to God, and the human has the divine similitude. To be an analogy requires a certain proportion of dissimilarity. In this sense, Origen holds creation as distinct from the eschaton, insofar as in the final consummation of all things, the subjugation to Christ—constant and lasting—without risk of a fall. Furthermore, divine image in the beginning is completed only in the eschaton with divine likeness.

Von Balthasar: Definitions of Hope

Von Balthasar’s treatment of salvation in Dare We Hope? runs into problems right from the title. First, to understand his meaning of hope is extremely difficult, because of his equivocation9 with respect to the word. At times, he seems to understand it in a weak sense, as when one hopes that he recovers from an illness.10 Elsewhere, von Balthasar’s hope for universal salvation seems to take on the character of a Christian imperative.11 Either case is problematic. Hope in the former sense can be misconstrued as an opiate that desensitizes us to the reality of the Judgment; in the latter sense it takes on the character of the theological virtue—the object of which is assurance of a future event. One can be assured of the Last Judgment, however, we cannot be sure of its outcome. Another problem with respect to von Balthasar’s position is its scriptural foundations. He suggests a division between the pre-Easter Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels, who highlights the Last Judgment through parables, and the post-Easter Jesus of John and Paul, who proposes a more favorable outcome of the end times. Von Balthasar asserts that synthesis of both is “neither permissible nor achievable.”12 However, one must ask a more fundamental question: Is such a distinction correct anyway? Having been written after the Resurrection, all the Gospels are post-Easter documents. In addition, Balthasar’s plea for an integrated understanding of justice and mercy13 finishes as something less than integrated, affirming a priority of mercy over justice.14 Thus, he succumbs to question-begging, as he wishes to maintain the imperative of love as crucial to the hope for the saved.

Synthesis: Spe salvi and Holy Saturday

Building on the good principles of the aforementioned authors is Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical Spe salvi. With respect to the eschatological orientation of Origen’s exegesis, Pope Benedict concurs: “Faith in Christ has never looked merely backwards or merely upwards, but always also forwards to the hour of justice that the Lord repeatedly proclaimed.”15 In the gaze toward the future, the Christian essentially meets Judgment. In contrast to von Balthasar, who perceives Judgment as a threat, Pope Benedict affirms that the Judgment is fundamentally a hope, the assurance that the injustice of history does not have the final word.16 God gives perfect justice in a way that this world cannot.

Lastly, Spe salvi gives us an indication of what hope in God and eternal life can do. Hope has two hands. With one, it consoles us: “When no one listens to me any more, God still listens to me. When I can no longer talk to anyone or call upon anyone, I can always talk to God. When there is no longer anyone to help me deal with a need or expectation that goes beyond the human capacity for hope, he can help me.”17 The other hand reaches out:

It is never too late to touch the heart of another, nor is it ever in vain. In this way, we further clarify an important element of the Christian concept of hope. Our hope is always essentially also hope for others … what can I do in order that others may be saved and that for them too the star of hope may rise? Then I will have done my utmost for my own personal salvation as well.18

The two hands of hope, which console and compel, also bring us back to the beginning of this paper. As believers, we rub against apostasy professed by those we most admire and love. One cannot avoid the dissonance one feels, personally believing in the Judgment and seeing those we love pretend as if it does not exist.

A liturgical experience might teach us the proper response. If you have the privilege to spend Holy Week in a Byzantine church, then you will hear at compline on Good Friday the lamentations of the Virgin Mother. In the dark before the tomb, chanters give voice to her laments and disbelief:

Seeing her own Lamb led to the slaughter, Mary His Mother followed Him with the other women and in her grief she cried: Where are You going, my Child? Why do You run so swiftly? Is there another wedding in Cana, and are You hastening there to turn the water into wine? Shall I go with You, my Child, or shall I wait for You? Speak some word to me, O Word; do not pass me by in silence. You have preserved my virginity, and you are my Son and God.19

Finally on Holy Saturday, the Lord responds to his mother and myrrh-bearers:

Cry not for me, O mother, seeing in the grave, the Son whom you conceived in your womb without seed. For I shall rise, and I shall be glorified, and as God, I shall exalt in endless glory those who honor you with faith and love.20

Let creation rejoice exceedingly, let all the earth be glad! Hell, the enemy, has been destroyed. Women, come to Me bearing myrrh: I am releasing Adam and Eve with all their progeny, and on the third day, I shall rise again.21

The voice of Mary before the tomb gives us the jaw-dropping reality of this life. Suffering and death leave us with question marks, anger, and hurt. God himself responds to that with hope—not a cosmetic hope that sugarcoats everything, but rather gives meaning and intelligence to the discord. Such hope, in its meaning-making, has the power to turn woe-bearers into the myrrh-bearers, the ones who go and proclaim the resurrection. The hope given to us by Christ’s resurrection does not give us the easy answer, such as the apokatastasis, but it consoles us with the logic of his providence and compels us with its force—giving us something worth smiling about before Patti Smith and giving us strength to embrace our wayward mothers.

- Jerome, “Letter 124 to Avitus,” The Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers Vol VI St. Jerome: Letters and Select Works (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1954), 240. ↩

- “If anyone maintains the mythical preexistence of souls, and the monstrous apokatastasis that follows from this, let him be anathema.” E. Grillmeier and T. Hainthaler, Christ in the Christian Tradition 2:2 (London: Mowbray, 1995) 404-405. ↩

- The project of the Hexapla and the fact that the bulk of his written work took the form of commentaries on scripture tell us that Origen was first and foremost a scripture scholar; they also indicate that, for him, theology was scriptural exegesis. Whatever may or may not be said about the Hellenizing character of his reasoning must be subservient to this fundamental observation about his work… It is important to note that the separation of On First Principles into four books, each with chapters and sections, is late and therefore potentially misleading. Origen’s systematic treatment of both the inspiration of Scripture and its exegesis in what we call book 4 of On First Prinicples does not simply constitute another item in a list of subjects, rather, it lays out the entire underlying sense of the work, As said before, Origen’s theology is exegesis. –P. Bouteneff, Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narratives (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 96. ↩

- 1 Cor 15:25; 27-28, in On First Principles 1.6.1; tr. Butterworth. ↩

- Jn 17:20-21 in On First Principles 1.6.2 ↩

- On First Principles, 1.6.2. ↩

- ibid., 3.6.1 ↩

- J. Ratzinger, “In the Beginning…”: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1995), 30. ↩

- Noted well by R. Martin in Will Many be Saved? What Vatican II Actually Teaches and Its Implications for the New Evangelization (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing, 2012), 173-176. ↩

- Dare We Hope?, 166. ↩

- “If God is love, as the New Testament teaches us, hell must be impossible. At the least it represents a supreme anomaly. In no case can being a Christian imply believing more in hell than in Christ. Being a Christian means first of all, believing in Christ and, if the question arises, hoping that it will be impossible that there is a hell for men because the love with which we are loved will ultimately be victorious.” von Balthasar, Dare We Hope?, 53. ↩

- ibid., 29. ↩

- Reflecting on Bernard’s image of the “two feet of God”—Justice and mercy—von Balthasar writes: “Still, in Bernard’s image, the divine qualities seem more to stand alongside one another than to be integrated with each other.” Ibid., 149. ↩

- ibid., 156. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Spe Salvi, 41. ↩

- Spe Salvi, 43. ↩

- ibid., 32. ↩

- ibid., 48. ↩

- Compline of Holy Friday, Ikos. The Lenten Triodion, tr. Mother Mary and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber & Faber, 1978), 619-620. With some adaptions. ↩

- Matins of Holy Saturday, also known as Jerusalem Matins. Ode 9, Ikos. The Lenten Triodion. With some adaptions. ↩

- Ibid., Ode 9, Troparion. The Lenten Triodion. With some adaptions. ↩

Recent Comments