- Can you give me some advice on the morality of anger? Is it always evil?

- Does the Church give practical moral norms for hiring in companies?

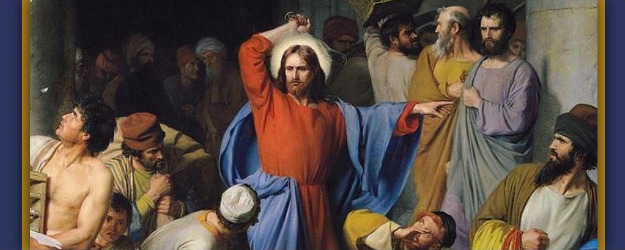

Casting out the Money Changers, Carl Bloch (19th c.)

Question: Can you give me some advice on the morality of anger? Is it always evil?

Answer: Anger is not always immoral. In fact, the emotion, itself, is good. It is one of 11 passions created in the human soul by God. The purpose of anger is to support the moral resistance to evil. A person who can never feel anger cannot resist evil.

The Scriptures are also clear that anger, itself, is not evil. “Be angry and do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your wrath” (Ephesians 4:26). Christ, who is the perfect man, felt all of the passions more deeply than people do today. This is because his soul was perfectly constituted. The Scriptures relate the fact that Jesus got angry on a number of occasions, always connected to the falsification of religion. However, Christ had “propassions,” which means that his passions could not arise before his reason came to bear—they could not blind him, and they could not lead him to do evil. He had no concupiscence. So, Jesus was exceedingly angry on some occasions, but did not lose his temper and, certainly, did not sin. Those who suffer from disordered passions, which is the inheritance of original sin, experience passion rising in themselves before they can think, which often color their judgment and tempt them to undue actions to resolve them. This is certainly true of anger, which can lead to murder in extreme cases. This could not have been so with Christ.

The value of anger is that it produces adrenaline so that when we are confronted with physical evil, we can resist it. Adrenaline also assists us in opposing moral evil. Thus, the purpose of anger is to correct both the evildoer and evil. In order to accomplish this, we must control our feelings and the accompanying expression of anger. It is never a good idea, for example, to lose one’s temper and throw the equivalent of what would be an adult temper tantrum. The only thing the evildoer hears is the emotion of the response, and not whatever reasonable concern there may be behind it. Often silence is the proper response. This allows the evildoer to know that one is upset and that an injustice has been done, but it avoids the possibility of unjust words or actions which are irrational and often cannot be taken back.

There are people today who are doormats to other people’s tyranny because they mistakenly think that anger is never a proper human response. They overlook real evil, and refuse to admit there has been an injustice. This is often motivated by a desire to be safe, to not have negative feelings and to be considered a saint by others. Note that this is an example of undue self-love—it is about the self and not about justice to the other.

The feeling of anger is meant to support our attempts to resist the evil of the other for the objective correction of the other and the injustice of the situation, in general. All reasonable attempts must be made to restore the order of truth.

There are times when the injustice of a situation cannot be corrected. We may have exhausted all reasonable attempts, but the injustice still exists. For example, we might have been treated unjustly by someone who is now dead. In that case, people have two choices: they can continue to let the anger fester until it dominates their whole emotional life; or they can choose to sincerely forgive the wrongdoer, regardless of whether he wishes to be forgiven or accepts this forgiveness. The former choice may destroy even good and loving experiences in our soul because we have only so much emotional energy. The latter choice is, in fact, the Christian response, recommended by the Lord as a condition for our own forgiveness. “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

Our Lord knew that we would all find ourselves in situations where we could not correct injustices done to us. So, as our healer, he recommends forgiveness. This forgiveness must have two characteristics. It must be based on grace and the forgiveness of Christ. Only one who has acquired the supernatural point of view can truly appreciate how integrating forgiveness from the heart can be. Second, it must also take time to prepare, and prayer, to actually accomplish. It is not an easy thing to truly forgive another. As an intense adult act, we should not rush into it. Rather, we should take care to always find the right moment, and, normally, this is only after we have had time for sufficient reflection. The world is not a perfect place, and forgiveness, motivated by love of, and for, Christ, is a powerful stimulus to divine mercy. It is also a good indicator that we are in the state of grace.

Question: Does the Church give practical moral norms for hiring in companies?

Answer: It is often difficult to make universal principles about so particular a problem. However, the Catholic tradition does propose some important principles, though their application must be applied with a good deal of prudence.

The most important principle has to do with the sin of “respect of persons” in the application of distributive justice, which is the recognition of the rights of the general community of individuals. Any choice of hiring or firing obviously concerns determining that one candidate is more suitable than another, or that a given employee is not doing his job, and, in fact, may be a hindrance to either himself, the company, or both. Distributive justice is not governed by a quid pro quo standard, in which one size fits all, based on arithmetic proportions. Instead, it is governed by a geometric proportion, in which one person may be more suited than another to pursue the common good of the economic community in question.

A general rule would be that suitability of employment in hiring should be determined by seeking the person who will best promote the product. Efficiency of operation is the key to this. Capricious hiring would be both unjust and irrational, in this regard, as it would easily militate against the common good of the product, and, so, the economy of the company. The only criterion should be, who will do the job best.

In the United States, discrimination in employment based on other factors, such as race, is against the law. However, we could conceive of a company in which someone who could relate to one culture more than another, might promote the product better. This would not be the case if we discriminated against a possible employee because some of the members of the company were racially prejudiced.

Qualifications for a given job should be clear and concrete, and reasonably promote the goods or services provided. Interviews should be objectively based on these. Tests might be indicated, but, as any examiner knows, the choice of questions is often rather subjective. Still, if someone cannot add, it would not be good to hire him or her as a cashier. Jobs which do not require people skills are often easier to fill than those which do. Prospective professors in colleges may have a plethora of degrees, but not be able to organize a lesson or command a classroom.

Today, affirmative action is a concern. In the book Business Ethics by Thomas Garrett and Richard Klonoski (ISBN: 0-13-095837-9), the authors distinguish three ways of interpreting affirmative action. “First, it can mean taking positive steps to recruit from minority or underprivileged groups. Second, it can mean that all other things being equal, the minority group member will be hired and promoted. Third, it can mean that even when all things relevant to the job are not equal, the minority group member will be given the job” (p. 27). The third interpretation exemplifies the sin of “respect of persons.”

Some politicians today support the idea that the third interpretation would make restitution for past wrongs. But it is difficult to see how hiring someone less competent and excluding someone more competent in the present could correct an injustice done in the past. Should we hire a surgeon who is a quack, just because he or she is of a given ethnic group, to the expense of a competent doctor?

Nepotism has often been a problem, even with regard to ecclesiastical appointments. Still it may not always be unethical. A relative may have a strong vested interest in the company, and if his qualifications are the same as someone else’s, then it is not a sin of respect of persons to hire him.

In the same way, promotions should only be based on one’s contributions to the company, not on one’s seniority. If too much emphasis is given to mere years of service, then people with real talent and innovation will be discouraged from contributing. At the same time, if employees have been told that talent and innovation are very important, disregard for these things will create unrest. As Garrett and Klonoski wisely observe: “A company is composed of people, not ciphers, so that the principle has to be adjusted to the concrete possibilities. What must be avoided is the arbitrary disregard of principle or the acceptance of unjust situations as immutable” (p. 31).

Pope Francis has been widely criticized for advocating the redistribution of wealth. He has been accused of being a socialist, and of interpreting this phrase with a socialist hermeneutic. Though the criticism is based on his advocating that governments be involved in the redistribution of wealth, this does not necessarily mean that it be done in a socialist manner. Governments could simply encourage the private sector to pay a just wage. In fact, he recently demonstrated that his understanding of redistribution of wealth is, rather, motivated by concerns of this kind: “The conscience of the entrepreneur is the essential place in which that search happens. In particular, the Christian entrepreneur is asked to contrast the Gospel always with the reality in which he operates; and the Gospel asks him to put, in the first place, the human person and the common good, to do his part, so that there are opportunities of work, of fitting work. Naturally, this enterprise cannot be carried out in isolation, but collaborating with others who share the ethical base and seek to widen the network as much as possible” (Pope Francis, Address to the Centesimus Annus Pro Pontifice Foundation, May 14, 2014. Quoted in Zenit, Internet News Service).

Recent Comments