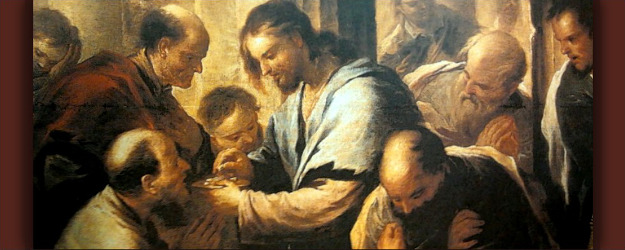

Communion of the Apostles, by Luca Giordano (c. 1659).

It has often been said that a picture is worth a thousand words. If so, it would seem that a mirror image of a picture must be worth twice as many words! But what if the mirror shattered into a myriad of pieces, and in every shard the same picture were reflected? How many more thousands of words would it be worth then?

The Holy Eucharist is something like the image of a man reflected perfectly and entirely in every piece of a shattered mirror.1 Only in this case, the image is the reality, and it is worth far more than a thousand words, or a thousand times a thousand words. It is worth one Word: the Infinite Word of God.

At some point, every comparison diverges from the reality it represents. The likeness of a mirror image multiplied necessarily falls far, far short of the reality that it represents, not because the simile is too fantastic, but because the reality is too wonderful. The real presence of God in the Eucharist is beyond the power of any literary device to adequately convey. It is beyond anything the imagination could produce or contain. It is beyond even our understanding. Many of our Lord’s own disciples could not accept it, but left him with the words, “This is a hard saying, who can listen to it?” (Jn 6:60).

That the infinite Son of God would give himself entirely to his beloved Church—not just his image or a mere symbol of his love, but his very self, whole and complete—is unfathomable by finite minds. That he would remain forever present to his people in a form that does not overpower us, but that can enter into and transform us, springs from an intellect surpassing all created intellects. It flows from a love surpassing all human love.

Even so, some did believe in him. When he asked, “Do you also wish to leave?” Peter answered for many by professing, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (Jn 6:68). As Catholics, we live and breathe those words of eternal life. They permeate our faith through Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the wisdom of the teaching Church. But they are not all obvious or easy to understand. Some truths are, but others seem far above our reach. With typical lucidity, St. Thomas Aquinas explained that some truths about God can be known by human reason, and of these, some are more easily accessible to faith than to reason. Other truths about God, he said, can be known by faith alone.2

In this way, truths about God are not entirely unlike other kinds of truth. The different branches of mathematics offer a helpful illustration of what St. Thomas is talking about. Everyone has “written in his heart,” so to speak, the most fundamental principles of quantity. For example, no proof is necessary to make the claim that “the whole is greater than the parts”—it is self-evident. From these principles, it is only a matter of simple reasoning to see that 2 + 2 = 4. The steps are few and plain; anyone can see it. That is similar to the way some truths about God are known, directly and easily.

To demonstrate the truth of the quadratic formula, however, requires some knowledge of factoring, and the process of completing the square. A beginning student of algebra must accept the formula “on faith” without having proved the quadratic equation himself, so that he can move on in the study of algebra. Later, when he is more familiar with algebraic processes, he can see the truth of it himself. That is like the second way of knowing truths about God, those that are more difficult and can be accepted by faith, but are still ultimately knowable by unaided reason.

The third type of truths, those that can only be known by faith, have a counterpart in mathematics, too. In the study of quantum theory, there are formulae that work well when applied to the world of physics. But even the quantum physicists may not be quite sure why they work. They accept them and use them, treating them as true, without fully understanding them.

In the realm of theology, some truths are easily seen, either immediately, or by simple reasoning. Psalm 53 can declare that only “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God,’” because we are surrounded by the effects of an intelligent creator. That God exists is apparent, both through evidence of things seen, and by a law “written on the heart.” In St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans, he declares: “Whatever can be known about God is clear to them: he himself made it so. Since the creation of the world, invisible realities, God’s eternal power and divinity, have become visible, recognized through the things he has made” (Rom 1:19-21).

The proposition that God is the first efficient cause of the universe is an example of something that can be known by reason, but that is more readily assented to by faith. The human intellect can eventually reach that conclusion, through the study of metaphysics, but, like the quadratic formula for the beginning algebra student, many just accept it on faith and move on.

Finally, similar to the way in which the formulae of quantum mechanics are out of the intellectual reach of most of us who have not studied that branch of physics—and, perhaps, even of many who have—there are truths of the faith that are simply beyond the reach of the limited human intellect. These truths about God, who is infinite, cannot “fit,” so to speak, in our finite minds. They never contradict reason, nor do violence to human understanding. They require no Kierkegaardian “leap of faith,” but they would never be reached by unaided human reasoning.

The doctrine of the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament is one such truth. It can be known exclusively through faith. Although it may not seem so at first, this is the most certain and sure way to know anything! Faith is an intellectual virtue, one of the three theological virtues that participate in the nature of God Himself, who is Truth, and “cannot lie” (Titus, 1:2). Through the medium of faith, the possibility of human error is removed, and the mind can rest satisfied in the truths faith reveals.

It is part of our common human experience that we rely on the word of others for a great deal of what we know. Consider how most of us know that the moon is really a rocky sphere, and not the luminous white disc it appears to be, or that all matter can be broken down into atoms that no one has yet seen. Most of us are not in a position to discover those facts directly; we depend for such knowledge on what we consider to be reliable authority.

Even in mundane matters, we rely on others for information. Strangers ask for directions from locals when in an unfamiliar neighborhood; people often check the weather report before planning the next day’s activities; a patient relies on wisdom gained from the education and experience of his doctors. And, in fact, nearly all current events that we call “news” are filtered through the written and spoken word of sources closer to the facts.

We depend on other fallible human beings for information and knowledge, and consider ourselves informed. How much more reliable is the knowledge gained from the infallible authority of “every word that proceeds from the mouth of God,” (Mt 4:4). St. John says, “If we accept human testimony, the testimony of God is surely greater” (1 Jn 5:9). With imperfect understanding, but with perfect confidence, we can accept the truths of the faith that are beyond our limited grasp.

So we accept with delight the knowledge that the limitless God has allowed himself to be contained under the appearances of a fragment of bread, and a vessel of wine, for the salvation of our souls; we have God’s word for it. It cannot be proved, and it does not need to be proved. It is something to be searched out in all its beauty—believed and treasured.

The Lord of all creation who made things as they are, alone has the authority to alter the natural order of created things. In this case, he declared that through the repetition of Christ’s own words, the substance of his body, blood, soul, and divinity should be joined with the appearances of bread and wine in the host and chalice when the substance of bread and wine are gone. He said, “Take this, all of you, and eat of it, for this is my Body, which will be given up for you.” And, similarly, he took the chalice, saying, “Take this, all of you, and drink from it, for this is the chalice of my Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal covenant, which will be poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins.” And then he asked his disciples to follow his example, “Do this in remembrance of me” (1 Cor 11:23-25). Faithfully, the disciples and their consecrated successors, forever after have obeyed his command, and in so doing, accomplish the unimaginable.

A student of mine once asked, “If it is true that the host at Mass is not just a symbol of Christ, but really Christ himself, how can we just walk up there and receive him? I mean, we aren’t good enough for that.” There are so many things that could be said in answer to that wonderfully humble and thoughtful question, but the first and most obvious answer is, “You are right!”

Apropos is the saying attributed to St. Francis of Assisi: Man should tremble, the world should quake, all Heaven should be deeply moved when the Son of God appears on the altar in the hands of the priest. None of us is worthy to approach God, much less receive him. None would dare to even think of it, were it not for the decree of our Lord himself: “Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (Jn 6:53). And so, at each Mass, when we hear repeated the words of Jesus at the Last Supper, “Take this, all of you, and eat of it,” humbly and gratefully, we obey.

Deeply aware of our own inadequacy, we repeat what was said 2000 years ago by a Roman centurion, “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof” (Mt 8:8). When the centurion first proclaimed those words, and asked that his servant be healed by the mere word of authority, our Lord was pleased with the expression of such great faith. The centurion’s servant was healed without ever being touched physically by the Healer. Encouraged by this encounter, we dare to beg, “Only say the word, and my soul shall be healed.”

With great faith in the power of God’s authority, we approach him, and in receiving him, we are transformed. Our dear Lord himself said, “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (Jn 6:56). Thus, St. Augustine declares in his Confessions, that through the reception of Holy Communion, Christ is not changed into us, like bodily food, but the recipient is changed into Christ. He transforms us into himself.3 By that transformation alone, do we dare to take God into ourselves. The 17th century spiritual author, Fr. Lorenzo Scupoli, was describing just that transformation in his prayer to our Eucharistic Lord, “… you desire to give me the whole of yourself as food and drink for no other purpose but to transmute the whole of me into yourself … for in this way, you dwell in me, and I in you; and through this union of love, I become as you are … through the union of my earthly heart with your heavenly heart, a single divine heart is created in me.”4

The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains that through the Eucharist, the bond of charity between Christ and the communicant is strengthened. At the moment of reception, there is an intimate union of hearts,5 that St. Cyril of Alexandria compared to a coalescence of two candles into one.6 We can meet Christ in many places, and in many ways, through the members of his Mystical Body, and in his image indelibly stamped on every human soul. Mother Teresa showed the world the suffering Christ in the poor of Calcutta, and in the innocent victims of abortion, and in her own generous heart. St. Damien demonstrated the great goodness of Christ in his care for the lepers of Molokai. St. Francis of Assisi was a living example of the holy poverty, and irrepressible joy of Christ. Among the great men and women of faith, and among the lesser ones, examples of the living Christ abound. In fact, any work performed out of charity brings Christ to those who experience it.

And of course, Jesus Christ, true God and true man, the Savior of his beloved people, is found in all truth and beauty in Sacred Scripture. But nowhere else can we meet Christ so perfectly, so completely, and so intimately as we do in what St. Thomas called the “Sacrament of Love,” rightly named because it contains God himself, who is Love (1 Jn 4:8).

In awe of Truth, we contemplate the Eucharist; yet, we will never fully understand it, and, happily, we don’t need to. Like trusting children of an all loving, all good Father, we can accept that it is so. That is enough. When the Beloved says, “Come to me … and I will refresh you” (Mt 11:28), his people will come, because for the one who loves, there is no room left for doubt; the heart is full. Ubi caritas, Deus ibi est.

- Fr. Stefano Mannelli, OSF, Jesus, Our Eucharistic Love, cf. p. 57, The Academy of the Immaculate, 1996, Massachusetts. ↩

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles, Bk I, Ch. 3, University of Notre Dame Press, 1991, Indiana. ↩

- Confessions, St. Augustine, VII, 10, Cox and Wymen, Ltd., 1961, London. ↩

- Unseen Warfare, Fr. Lorenzo Scupoli, Kadloubovsky and Palmer, Trs., Faber & Faber, 1963, London. ↩

- The Catechism of the Catholic Church, §1416. ↩

- St. Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on John 10,2; cf. Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, Ludwig Ott, pg. 394, §15, trans., Patrick Lynch (TAN Books and Publishers, 1960). ↩

Recent Comments