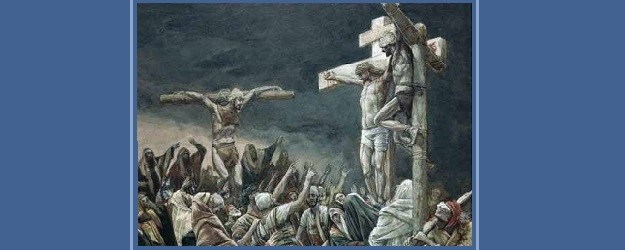

Christ pardoning the thief, Dismas by James Tissot

Question: I am a secular Carmelite preparing to make my vows. Can you explain the difference between religious profession and seculars regarding the virtue of religion? How would the vows of religion differ from my promises for life? Don’t we all have the virtue of religion even without making a vow?

Answer: In the Sermon on the Mount, Christ adds counsels of perfection to the commandments. He does this because the New Law of Christ is primarily, but not exclusively, the presence of the Holy Spirit in the heart of the holy Christian. As such, it presumes a rightness of intention which is much harder to live than merely exterior conformity to the commandments. Though all are called to exteriorly observe the moral law, the redeemed must do so from the love of God.

This purity of intention is threatened by the dross left over from Original Sin, often referred to as the fomes peccati (the tinder of sin) which is characterized by the three great lusts: the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life. The evangelical counsels of the Gospel address these three lusts by requiring the Christian to not only give up sin, but also to control unbridled, unreasonable desires for goods which lessen charity in us. Poverty addresses the lust of the eyes; chastity addresses the lust of the flesh; obedience addresses the pride of life.

Everyone is obliged to embrace these counsels according their state in life. Only religious are obliged to embrace these counsels under the aspect of a fixed way of life in everything. Since they imitate Christ perfectly by a special consecration in the Church, they embrace this way of life by choosing to put themselves under the obligation of sacrifice to God by a special title. Sacrifice is an act of the virtue of religion because, by it, a man in justice honors the obligation he has to attempt to repay God for all he has received from him. Objectively speaking, this means that those who embrace the vows of religion commit two sins when they fail to observe them. An act of unchastity would sin against both temperance and religion, and entail an act of sacrilege. The sacrilege would result from the religious person acting contrary to the holocaust he has made of himself by his vows.

Promises are often made by those in lay associations of the faithful, especially those who wish to be connected to various religious orders. These promises are usually made to the community, and not directly to God, so they would oblige the promised person to pursue the virtue involved but not place this directly under the virtue of religion.

Since Vatican II, in some lay associations of the faithful connected to religious orders, these promises may be deepened to vows. In the Carmelites, for instance, after a period of time in promises, the member may make vows of obedience and chastity, but not of poverty because of the duty of the laity to live in the world and sanctify it. This is in some ways a new area. One Carmelite Constitutions says: “With the consent of the community and the permission of the Provincial, a member of the Secular Order may make vows of obedience and chastity in the presence of the community. These vows are strictly personal, and do not create a separate category of membership. They suppose a greater commitment of fidelity to the evangelical life, but do not transform those who make them into juridically recognized consecrated peoples as in Institutes of consecrated life. Those who make vows in the Secular Order continue to be laypersons in all juridical effects.”

It would seem then that those who make promises simply pursue this as members of their Order according to the interpretation of the Order. Those who would make vows according to this special case, since they still continue as lay persons, would not formally add the further sin of the violation of the virtue of religion in justice but still pursue the counsels under the desire to increase the virtue.

__________

Question: It is my understanding that the paradise offered by Christ to the good thief on the cross is actually the limbo of the just. It became heaven when the soul of Christ appeared in limbo to preach his victory over death. He then led those souls to heaven. Is this correct? I think most Christians think Our Lord took the thief directly to heaven on the same day.

Answer: The question of the salvation of Dismas seems to raise many other more important questions. The promise of the Lord is made in Luke 23:43: “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.” The doctrinal difficulty with this question has been related to the issue of the necessity of baptism for salvation. Some Protestants have speculated that the fact that Dismas went to heaven without baptism by water argues against the necessity of baptism by water for salvation. Though the actual time of the institution of the sacrament of baptism is a matter of some speculation, this is actually irrelevant to the salvation of Dismas.

The promise made to Our Lord to Dismas has also become entangled in the issue of the existence and nature of Purgatory. Dismas was a thief and, perhaps, a revolutionary. Some would maintain that he could not go directly to heaven since, though the Lord had forgiven him his sin, Dismas had not atoned for the temporal punishment due to sin.

The solution to these problems is based on the idea of the baptism by desire (per votum). Baptism by desire entails the expression of faith in Christ, but which has not yet been ratified by baptism by water. The baptism of desire would include the desire for the baptism by water, which is its natural completion if the necessity is known, and it is possible. The explicit nature of this expression depends on where one is placed in the dispensation of salvation. Those who lived in the time of Abraham were bound to a much more implicit faith in Christ, than those who lived in the time of John the Baptist. So the thief in his confession of Christ experienced baptism by desire. He directly participated in the act of redemption which was Christ’s death on the cross. This is sufficient for salvation if baptism by water is not possible. Obviously, it would not be possible to baptize Dismas dying on the cross.

Purgatory is the resolution of all temporal punishment due to sin. For those who do not resolve for this by positive acts on earth, they must passively experience this resolution in the afterlife. Christ accepts the passion and death of the thief for the justice of his crime as a fitting atonement for the temporal punishment due to sin. So, his soul would have accompanied the soul of Christ to Sheol, or the limbo of the just, but then immediately have experienced the vision of God with those souls. The expression “this day” means that the thief went to heaven with Christ’s soul when Christ died on the cross for sin. He did not need to be evangelized with the three days Christ’s soul spent in Sheol, as he confessed Christ explicitly in his death on the cross.

St. Thomas Aquinas interprets the expression “paradise” in this way: “Paradise is threefold. First, there is the earthly paradise in which Adam was placed; then, the physical heavenly paradise, namely the heavenly Empyrean; and then, there is the spiritual paradise, namely the glory which is the vision of God. One must understand that it was of this last paradise that the Lord spoke to the thief; because immediately when his passion was accomplished, both the thief, and all those who were in the limbo of the Fathers, saw God in his essence.” (Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences, III, 2, 2, 1, qc3, ad 3)

/

There are times when theological discussions bring to my mind the insightful comment of Thomas a Kempis, In THE IMITATION OF CHRIST: “I would rather feel compunction (i. e., the state of grace,) than be able to define it.” Thrice blessed, of course, are those who can do both!

Sincerely,

Dr. William C. Zehringer