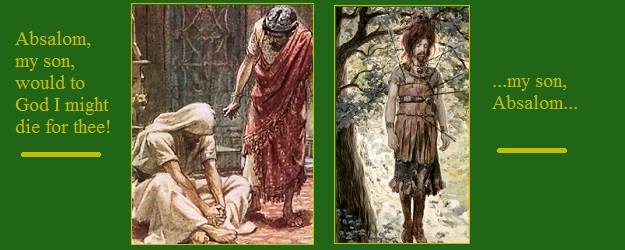

Paintings by James Tissot: “King David Mourning the Death of His Son, Absalom”

and “Death of Absalom”

There are epochs in every life marked by adversity: times when tragedy strikes, injustice reigns, or when overwhelming pain defies equanimity. One has to wonder at the heartbreak caused by human cruelty, frailty, or even just by nature run amok. Because we are intelligent beings who always act for an end toward some perceivable good, the question naturally arises: “What is all this suffering for?”

As Christians, of course, we have confidence that it will all come out right in the end. Our template was established long ago: Whoever takes up his cross and follows Me … will have life. (cf. Mt.16:24-28) Pursuant to the cross is the resurrection—of that we can be certain. Nevertheless, even the most stalwart Christian might ponder at times why all this suffering is a good thing, and not just a terrible, futile mistake.

Oscar Wilde caught a glimmer of the solution when he reflected in his De Profundis that:

Love of some kind is the only possible explanation of the extraordinary amount of suffering that there is in the world.

In the wake of the pop-culture craze of the sixties, when my generation was still young and impressionable, lightweight aphorisms floated around like popcorn in an electric kettle machine. “Flower Power,” “Make love, not war,” “Give Peace a Chance,” moralized songs, t-shirts and bumper stickers, along with the irresistible bright, round smiley face. “God is love” was an acceptable maxim when written in bold hippie font on a background of neon flowers. In that context, it suggested rather that, “‘love’ is god,” and it differed little from another still popular sentiment, “If it feels good, do it.”

About 2000 years earlier, the disciple whom Jesus loved solemnly and infallibly declared, “God is love,” (1John 4:8) but there were no neon flowers on his manuscript, and he seems to have meant something quite different. I don’t think suffering came into the definition of the word “love” as it was thrown about in the sixties and seventies, or in the general confusion that followed (except, perhaps, as a moral consequence). In the Scriptures, on the other hand, and in common experience, the two concepts seem nearly inseparable.

My son Absalom, Absalom my son: would to God that I might die for thee, Absalom my son, my son Absalom (2 Sam 18:33).

The anguished love that moved David to utter this cry is palpable. His pain reverberates in the heart of anyone who has had to stand by and witness the suffering, or death, of his or her child. The pain of losing a child—through sin or through death—is bitter. There is no other agony quite like it, perhaps because it is such a violent upheaval of the natural order of things.

Bear in mind that Absalom was not the exemplar of filial piety. He was the dearly beloved son of his father, King David, yet, he worked diligently to usurp his father’s authority in the kingdoms of Judah and Israel by means of flattery and deception. He slew his half-brother, the eldest son of his father and, finally, he gathered an army, rising up against his father, in an effort to seize sole leadership David’s kingdom. In that uprising, David’s more loyal men captured and killed Absalom as he hung from a tree by his hair; thus was ended the son’s infamous rebellion against a benign and loving father. Remarkably, it is at that point that King David uttered his heartbroken lament.

David’s love apparently knew no bounds. In that great love, he foreshadowed, or typified, the all merciful and all loving God, who forgives and loves his children without limit. He does so despite their foolish arrogance, their willful idiocy, their self-destructive reaction against right order, and legitimate, Divine authority—and all this despite their sin and selfishness. On honest reflection, everyone should rejoice to hear David’s lament, and to realize that God’s love is greater still, infinitely greater. The Incarnation of that infinite love, the Son of David, Jesus, heard and answered David’s prayer when He did die for Absalom, and for every other sinner. “No greater love hath any man than that he lay down his life for his friend.”(Jn 15:13) The greatest love of all was brought to fruition in suffering, and in death.

Not only the greatest love, but all human love, however fragile, is subject to suffering. Not long ago, I met an accomplished saleswoman who chattered agreeably about growing up with her twin sister. She recalled the fun they had had together. She spoke fondly of the crazy things her sister used to say and do. She even brought out her old family photos.

But much later in the conversation, she confided that a few years ago, her twin sister had committed suicide by driving her car off a cliff. “Of course, she meant to do it, so it was okay,” she reasoned. But something in her expression belied her and, she admitted, for at least a year afterward, she could hardly get out of bed each morning to face the pain again. Even as she spoke the shadow of that pain, of love betrayed, was in her eyes.

St. Francis, the poor man of Assisi, knew suffering, too. But for him it was a cause for joy. And in that transformation from suffering to joy, from darkness to light, St. Francis exemplified the great gift of Christianity. There is a scene in Felix Timmerman’s biographical novel, The Perfect Joy of St. Francis, which captures the irrepressible spirit of that saint, and illustrates well his awareness of the relationship between love, and the suffering that culminates, not in pain, but in perfect joy.

One late afternoon as they trudged along through the driving snow, St. Francis called to his companion, Brother Leo:

Little Lamb of God, even if all the Minor Brothers gave the finest examples of holiness and virtue, and healed cripples, and could make the blind see, drive out devils, and even bring the dead back to life—remember and note that perfect joy does not lie therein!

Brother Leo noted this in silence. Again St. Francis exclaimed:

Even if we knew all there is to know, and could predict the future, and read the secrets of men’s consciences and hearts, note that neither is that perfect joy!

Brother Leo noted this, too, with respectful silence.

St. Francis continued to enumerate for Brother Leo many things, wonderful in themselves, that do not constitute perfect joy. Finally, Brother Leo inquired of his mentor:

What then is perfect joy?

With delight, St. Francis proclaimed to Brother Leo:

When we arrive at the Portiuncula in a little while, wet to the skin by the snow and freezing with cold, plastered with mud, and tortured by a gnawing hunger, and then, when we knock at the door and the Brother Porter asks: “Who are you?” and we answer: “Two of your Brothers,” and he says: “You are lying. You are two tramps … Get out of here!” and … he angrily strikes us down and beats us with a club, and we endure it all willingly, without complaining and lamenting, out of love for Our Lord Jesus Christ—O Little Brother Lamb, note that that is perfect joy!

Then the exuberant saint unfolded his thought:

For above all the gifts of the Holy Spirit which Christ gives to His friends is the grace of conquering oneself and of suffering pain, injustice, and mistreatment willingly, for love of Christ! We cannot take pride in any of the other gifts, because God grants them to us. Why should we glory in something that is not ours? But we can glory in the tribulations of the Cross, because we take it upon ourselves of our own free will, and it is ours. I want to glory in nothing but the Cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ!1

What St. Francis realized that may not be obvious to all of us at first, is that there is an inevitable connection between true love and real suffering, and that the result of the suffering is the fulfillment of the love—that hard-won treasure. Any lover knows that to possess the beloved is joy. But to possess the All-Perfect Beloved is perfect joy.

And therein lies an accounting of our hope (1 Pet 3:15). Any suffering endured for the sake of God—for love of Him—leads ultimately to possession of God Himself. Our Lord decreed that, “Whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.” (Mt.16:25). To suffer anything out of love for Christ ennobles that suffering and makes it fruitful. But fruitful to what end? St. Thomas explained that it is the nature of love to transform the lover into the object loved. When the object loved is God Himself, the lover obtains God Himself. “Whoever remains in love, remains in God, and God in him,” St. John declared (1 Jn 4:16). And so it is that, finally, charity leads to the eternal happiness of union with God.2

It is as if every wound, injustice, injury, and inconvenience endured for love of Christ, is a brush stroke on an open canvas—the created soul. The paint is a luminous medium, rich as blood, applied by the Master Artist. Initially it may look like random and meaningless strokes, but gradually a distinct figure takes shape; it is yourself, but more beautiful than in life. As more strokes are applied, another figure emerges, embracing the first. It is He for whom you suffered, and who suffered infinitely more for love of you. It is the One who once said to St. Faustina, “Now rest your head on my bosom, on my heart, and draw from it strength and power for these sufferings because you will find neither relief nor help nor comfort anywhere else.”3 The composition may be dim at first, but over a lifetime, it becomes more clear and distinct. One day the completed canvas will take on another dimension, and everything else will pale.

All things work for good for those who love God (Romans 8:28)—all things. The good deeds we may do, great or small, the mistakes we make along the way, the suffering we endure, and even the most bitter pain—all of this works for good for those who love God. For, when borne out of love for Him, they foster a union with God right now, replete with joy. And that bond of grace that begins in our sacrifices, draws one nearer to perfect union with the Beloved in eternity where there is no shadow of pain. There is so much to be gained by our suffering!

Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends. (1 Cor 13: 7-8)

Truly, God is love.

Dear Ms. O’Reilly,

This morning, a good friend sent me your beautiful article, and it has touched me to the very core of my soul. Seven weeks ago, my 28 year old son died in his sleep from sudden cardiac failure, despite being in apparently good health for more than 26 years following open heart surgery to correct a severe congenital defect of the mitral valve. Timothy had stopped going to Mass when he left for college ten years ago, in an act of defiance stemming in part from his unresolved anger over the sudden loss of his younger sister from an undiagnosed brain tumor back in November 2000. My wife and I are not only heart broken over the loss of a second child, but have been filled with anxiety over the state of our son’s mortal soul. He was an exceptionally kind and giving person, loved by everyone who ever met him because of his gentle and patient nature. Close to 600 people attended his funeral Mass because of his tremendous example of love, and we cling to the hope of God’s mercy on him, knowing that our Lord ultimately judges the heart, not the externals. The haunting words of David’s lament over the death of Absalom have been ringing in my ears since the moment we learned of Tim’s death, and more than one person has said to us what you have expressed so eloquently in your article: if imperfect fathers can forgive their children, can we expect anything less from our Heavenly Father?

May our Lord grant you a blessed Thanksgiving, and thanks again for your insights..

In Christ,

Deacon Mark Kuhn