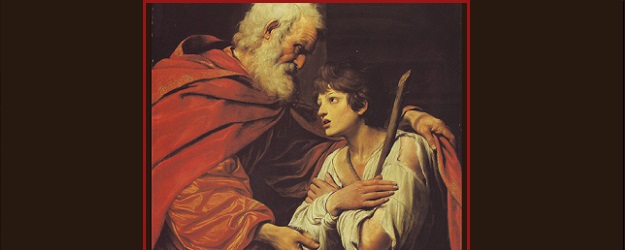

“The Return of the Prodigal Son” by Lionello Spada

There is an old Irish saying according to which there is an ebb and flow to every-thing except God’s grace. George Bernanos, in his Diary of a Country Priest, gives a touching illustration of that truth. It is the portrayal of a priest who believes himself, if not a total failure, at least a poor instrument of God’s grace. What he fails to see is the effect of his witness and his suffering on others. But his dying words, whispered in the ear of his friend express the profound insight he has been granted: “Grace is everything.” There is nothing that we have not received. The more we have, the more we are indebted to God. This debt is paid only in praising God for his ineffable grace, and in confessing that everything is his work. Grace is not merely a gift but also a task. As Flannery O’Connor noted: “All human nature vigorously resists grace because grace changes us, and to change is painful.”

Grace, however, is very difficult to define or even describe. In this it is like many things about which we speak rather glibly. We think we know what they are until someone asks us to define or explain them. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that grace “is favor, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life” (CCC §1996). Your typical English dictionary offers seventeen meanings or uses of the word grace. The first meaning listed (favor) is especially helpful in reflecting an important characteristic of grace. Grace is a gift, always having the connotation of something freely given. But just because grace is free and unmerited does not mean it is rare. In fact, it is a gift in the light of which all human life, all human action, take on new meaning. Some say grace is approximately synonymous with God’s love, or God’s own life within us.

Grace is always and everywhere available but it does not impose itself. It does not come unsought. It is one’s free decision that opens the way to grace. To put that a bit differently, grace is not magic. It does not work independently of nature. That idea is commonly expressed by saying grace builds on nature. It builds on the material it finds. If the material is rendered unmalleable by free decisions, grace is ineffective.

Much theological reflection has centered on the relation of “nature and grace.” As a gift from God, grace can be rightly described as supernatural. To say grace is supernatural, however, does not express what grace is in itself. What it does express is the absolute freedom of God in giving of himself to man.

“Nature” as contrasted to grace is a theological construct. It is a concept arrived at by abstracting from grace in man. But nature in isolation from God’s grace is never actually realized. Karl Rahner presents grace and nature not as two layers that penetrate each other as little as possible. Rather it is the case that man’s whole spiritual life is permanently penetrated by grace. Rahner describes grace as that which enfolds man, including the sinner and unbeliever, something from which he can never escape. Thus actual human nature is never “pure” nature, but nature necessarily included in a supernatural order.

In dealing with the problem of the relation of nature and grace, there are two extremes to be avoided. The first is denying the human in order to save the Christian (Jansenism). The second is denying the Christian in order to save the human (Nietzsche, Marx). Between those extremes is some form of Christian humanism which seeks a blending of the extremes, ranging from a negative minimum of avoiding damnation, to a maximum openness to the positive intervention of grace.

Grace is not some mysterious condition of the soul that lies beyond our personal experience. Nor is grace a theory to which one subscribes. It is the influence of the Holy Spirit in the soul. It is an adoption by God, promising an eternal inheritance. By grace, man reaches his highest dignity, a participation in the life of God; neither a confusion with divinity, nor a loss of personal existence.

The Lutheran theologian and pastor, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his book The Cost of Discipleship, makes a distinction that has become well-known. He contrasts what he calls “cheap grace” and “costly grace.” He describes first the former, “cheap grace,” as:

…the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession, absolution without contrition. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.

(and the latter as)

Costly grace is the gospel which must be sought, again and again, the gift which must be asked for, the door at which a man must knock. It is costly because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ. It is costly because it costs a man his life; and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life. It is costly because it condemns sin and grace because it justifies the sinner.

Over the centuries great controversies have arisen about grace, many arguments and treatises debating what grace actually does for us. Does it merely cover our defects, the evil within us as a result of original sin; or does it intrinsically heal us and raise us up? An even deeper controversy centers on the relation of grace and freewill. Does grace leave us free, and if so, how?

Rather than focus on the difficult theological investigations and controversies, we would do well to think of grace simply as God’s love for us. It is not that he loves us because we are good. Rather, we are good because God loves us. Why God loves us may be difficult to understand. But that is God’s problem. As individuals in actual circumstances, we cannot take it as certain that we are saved. Church doctrine holds that no one can have definitive and absolute assurance of being in the state of grace. We must remember we are still “on the way,” that we must work out our salvation “in fear and trembling.” (Phil. 2: 2)

St. Joan of Arc affords a wonderful example of the proper attitude in that regard. During her trial, Joan was asked: “Do you consider yourself to be in the state of grace?” The question was aimed at trapping Joan. If she answered “yes,” she would have convicted herself of heresy. If she answered “no,” she would have confessed to her own guilt. Her astonishingly simple and beautiful answer was:

If I am not, may God put me there; if I am, may He keep me there.

Recent Comments