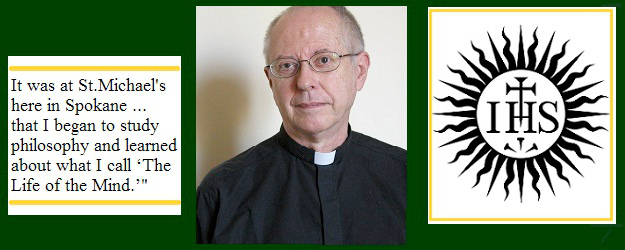

Fr. John “Jack” Navone, S.J., died on Christmas Day 2016. He was one of our regular contributors, and will be missed by all of us at HPR, and those who faithfully followed his thoughtful essays. May he rest in peace!

We are including two of his articles below, following his obituary.

_________

Fr. John (“Jack”) Navone S.J. died on Christmas Day 2016 from a brief battle with cancer. He lived a joyous, fulfilled and adventuresome life as a Jesuit priest, theologian, philosopher, educator, author, raconteur and a Professor Emeritus of Pontifical University, Rome, Italy.

John was born October 19, 1930 in Seattle. He grew up on Queen Anne Hill and attended St. Anne School. He went to O’Dea High School for 3 years and graduated from Seattle Preparatory School in 1948.

He entered the Jesuit novitiate of St. Francis Xavier at Sheridan, Oregon in 1949 and studied there for 4 years. He then attended Mont Saint Michael’s, Philosophate, Jesuit seminary in Spokane, WA. He received his master’s degree in philosophy from Gonzaga in 1956. From 1959 to 1962 he studied theology at Regis College, University of Toronto. He was ordained a Jesuit priest in 1962.

He received his doctorate in theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome in 1966.

John began teaching biblical theology at the Gregorian University in 1967, and spent his career at the Greg teaching in that department. He loved teaching and brought to it an excitement that only a person thoroughly impassioned by his life possesses. He shared the same exhilaration for life, friends and experiences in Rome, a city he adored, thrived and lived in for 47 years. He published a total of 23 books and many scholarly articles in several magazines. He spent his final years years of “retirement” teaching at Gonzaga University. Father Navone had been quoted in books and major media, which illuminated his career as a theologian as well as his love for people, the humanities, and nature. The highlight of his career/life was being noted by the current Pope Francis as one of the Pope’s most major early influences. It was John’s book, “The Theology of Failure” that shaped Pope Francis’s life view on patience. Pope Francis praised John’s book and said “(patience) is a theme that I have pondered over the years after my having read the book. The Theology of Failure, in which Fr. Navone explains how Jesus lived patiently.” The Pope added “patience” is forged in dialogue with human imitations.

John is survived by five siblings: brothers Joseph, James, George and sisters Helen Gleason and Catherine Mullally. He also enjoyed the company and conversation of numerous nieces and nephews most of whom reside in Seattle.

Funeral Mass was on Saturday, January 21, St. Aloysius’s Church, 330 East Boone Avenue, Spokane, Wa. 99202

Remembrances can be made to Regis Community Center, 1107 Astor, Spokane, WA. 99202

________

The Good of an Ordered Creation

By Fr. John Navone, S.J.

We live to know more than ourselves, even though “know thyself” remains our first duty. We delight in knowing. We often notice that when we begin a project or read a book, time passes unnoticed, almost as if we stand outside of time. Everything, that is, we find not merely admirable, but something that incites us, something that makes us realize that the world is more than ourselves, yet also includes us in some order we seek to clarify.

Aquinas deals with the question whether the truth is a special virtue (Summa Theologiae II-II, 109, 2). The question arises because the truth is primarily a question of the intellect, of both the intellectual and practical virtues. On the other hand, whether we act to tell the truth, when the occasion arises, indicates a moral attitude. Thus, the moral virtue of truth-telling means not only that we know the truth that we speak, but that we speak it, attest to it. The human good consists in using our minds properly.

Aquinas then cites Augustine, who said the good consists in “order.” The special character of the good consists in “order.” The special character of the good is the manifestation of a definite order. There is a special order in which our exterior words or acts are duly ordained to something, as a sign to that which is signified within us. And this is what perfects us through order—that is, we manifest in our words and acts the order of a thing that is. The good of our minds is to know and manifest this order.

There are various kinds of order we might encounter. The mind wants to know that this thing is not that thing. It strives to distinguish. It seeks to know and manifest the difference among things, including human things. The human mind implicitly assumes there is order among things because it looks for it. We have to be talked out of order with very subtle arguments or proofs to think that there is no order, or that the only order that exists is the one we impose on things.

The great Church Doctor, Athanasius, in his Discourse against the Pagans, stated what is, no doubt, the common view. It is right that creation should exist as he made it, and as we see it happening, because this is his will, which no one would deny. For if the movement of the universe were irrational, and the world rolled on in random fashion, one would be justified in disbelieving what we say. But, if the world is founded on reason, wisdom, and science, and is filled with orderly beauty, then it must owe its origin and order to none other.

The order is a willed order. It is not irrational, though its rationality is not a man-made rationality.

This order does not mean that human minds cannot know something of it, beginning from what is. The cosmos does not roll on in a random fashion.

There remain, of course, those who find no order in reason or reality. However, the fact is that the mind is made, not by itself, to know what is, and as best as it can, does so. We want to know, we have a longing to know, the order of things, and the various orders within this general order which, as Socrates said, it is made to be ordered by Mind.

An Intelligible, Coherent, Meaningful Creation

Our need for meaning primordially expresses itself in the narrative mode. Storytelling satisfies this need and desire by intending an intelligible, coherent, meaningful world. Our myths and stories of God, a constant in human history, witness to our spontaneous conviction that order prevails over chaos, that reality is intelligible. They imply our will to believe that the world is ultimately intelligible, and that the absurd is not the last word.

Our desires for meaning and for knowledge strive to join our narrative expression with our will to believe. They give rise to the stories that provide the context for belief in God. The dynamics of our desire to know uncover a meaning which anticipates some form of narrative expression. This occurs even though our desire to know leads through apparent meaninglessness. The desire of both the desire to know, and the will to believe in God, merge in their intention of an intelligible world. The meaningfulness of such a world is experienced, lived, and felt within some narrative framework; for life without story would be experienced as absurd.

Story links our feelings with the reality of ourselves. Story is the integrating structure that organizes our feelings, and forms a sense of continuous identity with our past and future. Story brings a temporal context of meaning to the immediacy of the moment; otherwise, we would be forever losing our grip on the reality of our own identity with the passage of discrete moments. Mental balance involves keeping in touch with the narrative sequence underlying our thought. The impulse to tell, or retell, stories gives the lie to the claims that the world is absurd; for it is a way of ordering the world which implies that the world is intelligible. The dynamics of narrative consciousness in storytelling intend a coherent universe, and disclose our world-ordering impulse and power.

A spontaneous narrative consciousness persists and functions on the premise that there is a permanent meaning at the heart of things. Its resurgent tendency to shape the world with myth and story, despite every obstacle, implicitly affirms that the universe is not absurd. Ordering the coherence of the universe is not futile; it testifies to a primal conviction that reality lays itself open to being ordered in a comprehensible way, and that this would not take place if there were a primal conviction that the reality is absurd. The spontaneous world-ordering acts of storytelling involve a primal consciousness that is so intimately one with its world that it has not yet made the theoretical distinction between the human subject, and its world. Such spontaneous primal thinking does not need to question whether the universe, in itself, is intelligibly ordered, for ordering (subject) and recognizing the world as already ordered (object) become different only to theoretical judgment. The spontaneous narrative consciousness involves as order that is also the order of the totality, embracing both subject and object.

Narrative activity intending a meaningful world is the ontological ground for affirming that we are empowered to create such a world. Human vitality takes the form of intentionality; it is given to creating meaning, and to affirming its own identity. Animal vitality, on the other hand, simply acts according to inalterable biological routines. Narrative consciousness is ultimately rooted in the ontological power of being, or Being-Itself (God). Our participation in this power grounds our ineluctable need to order the world through stories. The dynamic of narrative consciousness postulates the supremacy of an intelligible universe over an indifferent one, of meaning over absurdity, of being over non-being. The persistent workings of our narrative consciousness postulate our participation in the power of meaningful being over and against the void, the possibility of new meaning revising our sense of reality, and relating us in new ways to the world. Our will to believe in an intelligible world activates our narrative consciousness, and the worlds of meaning that it opens up to us. Reflection on our narrative consciousness becomes that basis for our awareness of our desire to know, and the postulate of a rational universe, a world-to-be-known in a questioning and critical way. Our narrative consciousness (the dynamic of storytelling) posits that there is intelligibility to be grasped in the world; otherwise, we would not have sought it out. There would be no storytelling without the anticipation or foreknowledge, however vague, of some story to be told. And we would not continually revise our stories (and histories) if we did not anticipate some further intelligibility. Storytelling is undertaken on the premise that the real is comprehensible, meaningful, and intelligible. (Even our question about the intelligibility of the real posits intelligibility as the horizon of our questioning).

Our Structured Wonder

The affirmation that God speaks in history presupposes a basic metaphysics. To speak, or not to speak, is ultimately a question for metaphysics.

Metaphysics is neither some vague view of life, nor some subtle intuition of Being. It is not a general account of reality, nor a process of linguistic clarification. Metaphysics is a structured anticipation of what is to be known, and the basic component in that structure is human wonder about human experience.

This wonder is expressed in two complementary types of question: a what-question or a why-question, and in another mode, whose satisfaction is expressed in a simple “Yes” or “No.”

Our structured wonder is often unformulated, or thematized, as it was by Aristotle; nevertheless, it is an invariant structure which grounds metaphysics. This invariant structure is shared by all humankind, always and everywhere. It is a dynamic structure which pushes for reasons (why?) and for truth (is it so?).

The dynamic structure of human knowing involves many distinct activities of which none by itself may be named human knowing. It is the total combination of experience, understanding, and judgment, which assembles itself consciously, intelligently, and rationally. One part summons forth the next, until the whole is reached: experience stimulates inquiry, and inquiry leads from experience, through imagination, to insight, and from insight, to concepts, which stimulate reflection (the conscious exigence of rationality). Reflection marshals the evidence to judge “Yes” or “No,” or else to doubt, and so renew inquiry.

We are a part of history. Because of our structured dynamism of wonder, we inevitably question our historical experience, and are also questioned by it. The objective, dynamic, world-order of which we are a part, raises questions for our understanding. The human dynamism of inquiry is an integral part of the developing world-order, of the interlocking, created, temporal universe which is history.

How does God “speak” in history. Departing from the material aspect for the meaning and truth of the expression “word of God,” we can understand the prophetic dictum:“The word of the Lord came to me,” as an interpretation of history in which the proper judgmental element is supplied by prophetic light, and the formal element by the ideas conceived in a human way by the prophet or writer.

God uses the things of the universe to convey his mind, as we use the written and spoken word to convey ours. For Aquinas, the movement of a pen, or vocal chord, is not less subject to our dominion than the course of events is subject to divine providence. The intelligibility of things derives from what they are, and from the Mind that employs them to express Itself.

Generalizing this Thomistic principle, we may say that the totality of history is God’s word. Nor is history—the totality of the created, developing, world-order—an inferior means of communication, as if words openly stated the mind of the speaker, whereas one could only infer from events the mind of God. Words are just black marks on paper, or vibrations in the air, apart from the intelligence of the speaker or receiver. In themselves, they are just data, potentially intelligible, on the immediate level. The totality of history is a divine creation, no more unwieldly an instrument of meaning than the human artifact of language.

Both truth and meaning are, strictly speaking, in the minds of persons, and in their minds only. Words in an unknown language, whether written or spoken, have no meaning for us. The lack is not on the page, in the transmitted vibrations, but in ourselves. We are the basic source of meaning for the document, the vibrations, the events; and the greater our understanding of the language, and of the subject written or spoken about, the more meaning they have for us. This does not imply meaning is subjective; rather, the ink-marks on paper, the vibrations, the events, all are only signs of meaning, and not the meaning of truth itself.

The marks, vibrations, and events can be signs of meaning, and there can be a correct meaning, which comes only through long efforts at understanding. Over a period of time, the documents, words, or events, might have meant something different to each successive generation; however, the meaning need not be opposed. The first understanding might have been correct, but inadequate; and basically what was developing was not certainty, but understanding. By the same token, our understanding of documents, and of the dynamic world-order of the created universe (of God’s word, history) can develop.

Evolution and Creationism

God reveals himself as the ultimate source of revelation in all its phases. His primary revelation for us is the visible world he created, and through which he speaks. The totality of history is God’s word; the one universe with both its natural and supernatural components, the magnalia Dei in history, and the operations of human beings; the entire dynamic of the world-order, from beginning to end, with its sacred and secular aspects.

For the community of Christian faith, the form, or structure, of human history has already been given in Christ, its permanent meaning through all material changes. The Father sends the Son, whose Incarnation assumes the material universe of time and space (history) into the Trinitarian life. The Father and the Son send the Spirit for the definitive work of sanctification. The three Persons come to inhabit the souls of the just. The events of history, the material element of this phase of revelation, will be completed at the end of time when the number of the just has been completed.

On the subjective side, there is the inner light needed to interpret the objective, and the historical. This light is necessary because the supernatural component of history is beyond the penetration of native human intelligence, and judgment on the subjective side.

In Offenbarung als Geschichte, W. Pannenberg affirms that the idea of the supernatural should be excluded because everything that happens in history is the expression of the working of the one triune God. He affirms that God’s self-revelation, through his deeds, is open for everyone to see in “ordinary history.” There is no need of faith, or supernatural aid, to recognize this. Ultimately, it takes the whole of history to manifest God.

The whole of history cannot adequately manifest God. Only proper knowledge of God can fully meet the question of what God is. Reception in the intellect of an intelligible form, proportionate to the object that is understood, is necessary for proper knowledge. This knowledge is an act of understanding in virtue of a form proportionate to the object; hence, proper knowledge of God must be in virtue of an infinite form, in virtue of God himself. Such knowledge surpasses the natural proportion of any possible, created, finite substance, and so is strictly supernatural.

Whatever knowledge history mediates of God will be analogous. The sacred is always beyond whatever knowledge we have of it. Analogous knowledge provides the intellect with some lesser form that bears some resemblance to the object to be understood and, thereby, yields some understanding of it. Because history, which mediates our knowledge of God, differs from the object to be understood, which is God himself, it must be complemented by the corrections of the via affirmationis, negationis, et eminentiae as in natural theology.

All spheres of the profane mediate the sacred; the character of the mediated knowledge is analogous. Knowledge of God, mediated through history, does not. and cannot. fully satisfy the human intellect. Such knowledge answers some questions. and raises others. Because it is analogous knowledge, the more we learn about God through the mediation of history, the clearer it becomes that there is much we do not know.

The meaning of history is measured by the infinite mind of God, and unrestricted by human conceptions. Because the meaning of the divine word cannot be exhausted, the meaning in revelation will never be exhausted. God alone knows the meaning of history. Paul spoke a word which is his and God’s, however the meaning is limited by the meaning which Paul gave it. History, as the totality of creation with its natural and supernatural components, is the word which God alone speaks in much the same way that we move pen and vocal chords in revealing ourselves.

We live, and move, and have our being within the word, history, which God speaks. Our spirit is marked by its questioning character, and almost constituted by inquiry. Our understanding of God will be mediated by the word, by the totality of history, in which our existence is rooted. It will be mediated by the dynamic world-order; consequently, our performance in questioning history implicitly manifests our dialogue with God, who speaks it. Implicit in every human inquiry is a natural desire to know God by his essence; implicit in every human judgment about contingent things is the formally unconditioned/without limitation that is God; implicit in every human choice of values is the absolute good that is God. We are a component of the word, and question it. In the dynamic of the question, God speaks, as the question-raising and question-answering Mystery in human history, even if implicitly and anonymously.

Bias, Meaning and Meaninglessness

History, the word which God speaks, triggers the human dynamics of the question. It raises questions and stimulates inquiry. It constitutes our precarious situation with the possibility of failure, or of fuller development. The word, which God speaks to us and which “contains” him, offers possibilities of human development in the dynamism constituting human consciousness which may be expressed by the imperatives: be attentive, be intelligent, be reasonable, be responsible. The imperatives regard every human inquiry, judgment, decision, and choice.

Any failure to be human implies an abdication from history. Our dynamism for inquiry is a part of history which makes us responsible to history as God’s word. As a part of God’s historical word, we transcend ourselves in answering that word through the intelligence of our inquiry, the reasonableness of our judgments, the responsibility of our decisions and choices. The absence of intelligence, of reason, of responsibility in our inquiry, judgment, decision and choice, distances us from history, from the meaning with which God actually constitutes history as his temporal self-expression.

History is ultimately what it means to God who freely speaks it. In this respect, history is what it means, and history means what it is. Meaning constitutes history. Meaning and existence are convertible. God is uncreated Meaning creating meaning; God is eternal meaning creating historical meaning. All spheres of the profane mediate the sacred; all spheres of historical meaning mediate the meaning of the supra-historical from which it derives. Limited meaning bespeaks infinite Meaning; historical meaning bespeaks eternal Meaning. In this way, history is God’s limited, temporal self-expression: it is the limited, temporal expression of his meaning. Meaning is God’s “speaking” in history; rather, God “speaks” history as Eternal Meaning expressing Itself in temporal meaning.

In virtue of our existence, we participate in history; in virtue of our meaning, we express God’s historical self-revelation. Only the meaningful is desirable (lovable); therefore, only the lovable mediates God’s self-revelation. The pure desire to know the meaningful is an intrinsic component of our make-up, even if it does not consistently and completely dominate our consciousness. It is our openness to history as fact and decision, for love is the proper emanation of desire. The achievement, which is always implied in our openness to history, is a question of the pure, unrestricted desire’s full functioning, of its dominating consciousness through precepts, methods, criticism, a formulated view of knowledge, and of the reality our knowledge can attain.

Divine grace brings openness as gift, when our pure desire to know the meaningful is no longer restricted to the limited and the historical, even though it conditions it, and is conditioned by it. Openness as fact (the self as ground of all higher aspiration) and openness as achievement (self-appropriation) which arises from the fact, are an openness to history, to created meaning extending from the beginning to the end of time, the finite expression of uncreated Meaning.

The possibility of openness, defined by the pure desire for meaning, is intended for openness as gift, which implies the enlargement of a horizon that is not naturally possible for humankind, because such an enlargement is beyond the resources of finite consciousness. Openness as gift involves the transformation of the subject when it is aware of itself as the gift of self by God to self. It is awareness of personal relations with God. It is the actual openness of the natural desire to the ultimate Meaning of history, mediated by the temporal, limited meaning of history.

We are made for meaning. Our pure, unrestricted desire for meaning enables us to inquire into everything about everything. It implies a desire for unlimited participation in history, in created meaning, through successive enlargements of our actual horizon.

The enlargement of horizon, following upon grace, conditions our interpretation of history, of created meaning, which we interpret according to a faith principle. History has a new meaning which results from “adding” the supernatural; however, the condition is not mathematical. It is the intimate and complete transformation of all the historical, of the human, so as to give it, not a new material reality, but a new meaning. Christian marriage, for example, may differ little in appearances from non-Christian marriage; however, it is different, because its meaning is different: it has the meaning of the union of Christ and his Church (Eph 5).

Creator, Creation and Revelation

Creation, according to Thomas Aquinas, is the primary and most perfect revelation of the Divine; therefore, if we do not understand creation correctly, we cannot hope to understand God correctly.

St. Bonaventure and Blessed John Duns Scotus held that the whole of creation was the necessary preparation for the divine Incarnation in Jesus, the Human One. The fleshing of God was not a later rescue attempt to put the original, failed plan back on track. Fall or no fall, it was lovingly willed from the very beginning.

Two thousand years ago, the human Incarnation of God in Jesus happened, but before that, in the original incarnation of the amazing story of evolution, God had already begun the mysterious process of becoming flesh by participating in creation itself. In this respect, the Incarnation of God did not only happen in Bethlehem, 2,000 years ago. It actually began 14 billion years ago with a moment we call “The Big Bang.”

Cosmologist and cultural historian, Thomas Berry, points out that Jesus did not come into a world, added on later, so to speak, as a necessary afterthought; he came into a world that was made originally in and through himself as the creative context of existence. Berry identifies the Christ story with the story of the universe, the revelation of the Logos and Love that is the origin, ground and destiny of creation. The Christ story expresses the holiness of creation itself.

Against any denigration of the material world, Christianity offers the vision of a beautiful, created world that can lead towards the spiritual, informing presence of the Word of God. But at the same time, the very goals of philosophy—awareness of the intelligible and purification of the soul—are taken up and rendered universally possible through our faith in God’s redemptive drawing us towards eternal life. In this perspective, Christianity can be shown to be not only a “religion” that is primarily opposed to pagan religious practices, but a rational philosophy that surpasses the Platonism obsessed with this material temporal world as the cause of unhappiness, and hence emphasizing the need for us to remove ourselves from absorption from the world, and contemplate ever more deeply eternal verities and archetypes.

The Christian liturgy resists Platonism’s aversion to the material temporal world through its vision of a liturgy in which the one Creator of all acts in the community, drawing the world to its consummation: Christian worship draws the hearts and minds of the faithful to Christ, and through Christ to the one Father of all. In the sacramental mode of its liturgy, the world acknowledges and celebrates its very being as flowing from the Eternal Now of God, and in each passing moment, moving inevitably towards its divine fulfillment in both the Love that sustains the cosmos, and in the Logos that is its meaning.

The liturgy is a primary source for Christian thought about God, creation, redemption, and related doctrines. This was a feature of early church theology, summed up in the phrase lex orandi lex est credendi: the rule of praying governs or constitutes the form and content of believing. The liturgy both forms and expresses human beings in the Christian faith, in any given age or tradition. The deep structures of what it means to remember, to praise, to bless, to give thinks, to invoke, to offer sacrifice, and to supplicate are at the heart of Christian worship and its cosmic relevance.

Beliefs, History and Metaphysics

Attempts to banish natural theology only show why we need it. Some claim that philosophy is dead because it has not kept pace with modern developments in science, particularly physics. For them, scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge. They claim that both philosophy and natural theology have passed away because the traditional argument from the order apparent in the structure and operations of the universe to a transcendent cause of these, namely God, is wholly redundant. The apparently miraculous design of living forms can appear without the intervention of a supreme being, a benevolent creator, who made the universe for our benefit. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something, rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist.

Although the universe could have been spatially and temporally chaotic, it isn’t. We know that the observable universe is composed of a number of types of entities and forces whose members exhibit common properties, and are subject to a small number of simple laws. From chemistry, we learn that elements share well-defined structural properties in virtue of which they can, and do, enter into systematic combination; from physics, we learn that these elements are themselves constructed out of more basic items whose properties are ever purer and simpler.

Why is there order rather than chaos? If there had been chaos, the question would not arise because we would not exist. Cosmic regularity makes our existence possible. The underlying issue concerns the enabling conditions of this order itself. Some reason that, while events in nature can be explained by reference to the fundamental particles, and the laws under which they operate, natural science cannot explain these factors. Natural explanations having reached their logical limit, we must conclude that either the orderliness of the universe has no explanation, or that it has an extra-natural one. The search for the source of order must reach a dead end if scientific explanation is the only sort there is. It is not, however, the only sort; there is also explanation by reference to purpose and intention.

The universe’s otherwise inexplicable regularity will have an adequate explanation if it derives from the purposes of an agent. Inasmuch as no natural agent could have made the universe, we must conclude that the only possible explanation of its regularity is that the natural order has a transcendent cause outside of the universe, which introduces the idea of a creator God.

Aquinas, and others in the Western natural-theology tradition, argued from the character of the universe to the existence of its transcendent cause. They were acute enough to describe that original source of the being and character of things as an uncaused cause, and not as the cause of itself. That was a matter of logical coherence since the idea that something could create itself from nothing, in itself makes no sense, being that the “something” was God. In order to create, one first has to exist.

The basic components of the material universe, and the forces operating on them, exhibit properties of stability and regularity that invite explanation. Science cannot provide an ultimate explanation of order.

_________

The Problem of Evil

By Fr. John Navone, S.J.

Human failure, whether culpable or non-culpable, is a universal human experience. Death, the lot of humankind, is apparently the ultimate failure, raising questions of God’s existence, goodness, and an after-life. Whatever the answers, death remains dreadful and communicates a terrible sense of failure.

The failure of history to produce Utopia has disillusioned idealists of every era. Every age records the evil of its failures, its dramas of oppression, collective suffering, deportations, massacres, and humiliations. Every age chronicles fresh social injustices, wars, greed and exploitation, in which we create tragedy after tragedy for ourselves. The idea that there has to be a human fulfillment in history, that the religious, social, or political millennium will come in time, rather than at the end of time, or outside of time, is debated. Regardless of the position taken in the debate, the fact remains that no age has been without the profound experience of historical failure. The historical process of itself has not produced universal peace and brotherhood. The apocalyptic biblical view of the human condition implies the impossibility of human freedom, and fulfillment within the historical process. Disappointment in the outcome of historical events leads to liberation from an illusion, or self-deception, that temporal beatitude constitutes salvation. Historical failure, whether culpable or not, still remains a kind of dying.

There is also a sense in which the future fails. Frequently, persons feel that they have no future, whether in their present historical situation, or in terms of an after-life. To be without either kind of future indicates a state of oppression or destitution, often reflected in contemporary literature or drama. Having nothing to remember implies having nothing to look forward to; on the other hand, an obsession with evil memories promises a future that is no future at all.

The Christian community of faith’s remembrance of the transcending love of its crucified and risen Savior empowers it with a future that transcends the ultimate failure of sin and death; remembering redemption redeems the future, transforming death into a transition in life rather than the ultimate failure of life.

The meaning of things is a part of their reality. The meaning of Jesus’ death, Christians believe, is different from any other death. It represents a unique reality, inasmuch as the meaning of a process is only fully understood in the term of that process. The meaning of Jesus’ death is only grasped by the resurrection faith in which Jesus’ death terminates. Jesus had attached a special meaning to his sufferings and life-giving death, as part of God’s plan and purpose (Lk 9:22; 13:32; 18:31-33); they would have important results in which his disciples would share (Lk 22:15-20, 28-30). The disciples believed that this meaning explained their experience of the Crucified and Risen Jesus. Hence, the reality of Jesus’ death, as well as that of his suffering and failure that were intimately linked to it, is rooted in the meaning which Jesus had given it, and which his disciples recalled. Failure, suffering, and death had been given a new meaning; they had been transformed into a different kind of reality, a new reality, a healing, transforming and liberating reality.

Through the power and meaning of divine love, everything is a grace working for our good; even failure, suffering, and death are endowed with the possibility of a Theophanous quality that both illuminates and transforms the world. In fact, the wisdom of the cross suggests that, perhaps, the best way of healing and enlightening the world is through the acceptance of failure, suffering, and death in the name of the absolute truth, love, and goodness of God. These are the effective means of the divine wisdom for the communication of that truth, love, and goodness which save the world by empowering it to transcend those evils which are genuinely lethal to the human spirit. Jesus accepts failure in his Father’s name, and his Father accepts the failure of his Son, because it is what his Son is that counts, rather than how he succeeds by purely human standards. Christians believe that we are ultimately regenerated by this mutual acceptance of Father and Son through the medium of failure and death.

The endurance of suffering, evil, and death is not a passive posture; rather, it requires, in its deepest Christian sense, a radically graced adherence to God, Eternal Life, and Love Itself.

Breakdown and Redemption

Healing, as a part of Christ’s ministry, expresses the transforming and enabling power of his grace, and of what God does for us. Just as when we hear of the wisdom of God in the Bible, for example, we think of how God’s action make us wise; so when we hear of God’s justice, we should think of that act by which he makes us just. God’s justice, in other words, like his goodness and compassion, is not God’s reaction to our behavior, but his initiative, quite irrespective of our behavior. God is free to do what he wills, and his freedom takes the form of acting so as to change us. It is a serious mistake to think that “justification” means a change in God’s attitude without effect in us. On the contrary, what changes is that we become the locus of God’s free activity. Unprovoked, unconditioned, and unconstrained by any other agent, God steps into the void and chaos of created existence, and establishes himself there as God.

The mystery of the cross tells of the place where the wretchedness of the created world, and the total failure of human resource or human virtue, is most fully exhibited. Where else could we see God’s absolute liberty to be God, irrespective of any external conditions? And where but in our own empty and hellish dereliction could we find what it is to trust, without reserve, in God’s freedom exercised for our sake? What gives us ground to stand before God is God: God has, in Christ, taken his stand in the human world, and answered for, taken responsibility for, every human being, quite apart from any achievement or aspiration on the part of humans.

Christian life is essentially the outworking of Christ’s life within us, expressing the Spirit of Christ poured into our hearts. The incarnate Lord was not merciful, generous, forgiving, and so on, in order to win approval from heaven, since heaven was his very environment. His good works are the expression of who he is.

The generous self-giving of the Triune God has its imperatives. There is nothing good in us that is not given; therefore, we are, beyond all possibility of repayment, fundamentally indebted. That awareness of indebtedness has the effect of making relative and questionable all our claims as human beings to have an absolute right of disposal over what is concretely and materially ours. We are called to freely give what we have freely received. We have been graced to become gracious towards others. What we believe to be our own is, in fact, given to us so that it may be shared: it is owed already to those whose need is greater.

What would society look like if a dominant motif in Christian life were gratitude, a detachment from possessions, grounded not so much in any doctrine of the evils of the world’s goods, as in a recognition that God’s gifts are restless in the hands of the receiver until they are given again, and that our rights of possession, in and over the material world, are systematically undermined by the awareness of the givenness of all things, spiritual and material.

The theological principle of God’s prior generous action in all things, bound up in our relation to him here, spills over into some extremely practical considerations. What is it to recognize in the concrete circumstances of one’s own prosperity or welfare the presence of divine action. It is, without doubt, to recognize that the apparently static things that secure our prosperity are carriers of God’s love, and that, therefore, they cannot sit still with us, they must not be prevented from being active signs of love. When we try to hold on to them, we make empty our claims to be dependent on God for our spiritual security, because we implicitly deny that God is active in all his gifts. Just as children receive their life from their parents, generous lives reveal the true children of the Generous One.

Overcoming Human Failure

Despite the experience of evil and failure on its many levels, the Christian preserves a fundamental optimism towards the world; not the optimism of agnostic humanism, but of the believer, who knows in faith that the world has been taken, radically and irrevocably, into the loving care of the Father, through and with and in Christ. It is an optimism that endures in and through death, disaster and sin, because the Christian knows that it is in and through Christ’s life-giving death that the power of his resurrection is communicated throughout the world. The Christian must be optimistic, then, but not utopian: optimistic because Christ has been raised from the dead as the first fruits of those who are subjected to God the Father; not utopian, not deluded into thinking that the inherent structures of the world can, of themselves, permanently bring peace and happiness.

Christian realism resists both the tendency to stress this-world values in such a way that the values of the world to come are neglected, and the tendency to stress the values of the world to come in such a way that the values of this world are neglected. Either tendency not only excludes true values, but in doing so seriously distorts the values that are retained. Pelagianism, an example of the first distortion, assumes that the human mind and heart can achieve the triumph of the Kingdom of God in this world permanently by mere human means. It often takes the form of some political messianism which stresses the present, and disregards the ultimate future. Quietism, the other extreme, is a failure to live up to the Christian vocation to use all the human means that learning and intelligence offer to create good social structures. The Christian seeks to avoid these two extremes of failure, doing everything or doing nothing, by relying on God’s grace, and contributing to the creation of a new world.

Christian realism recognizes that human failure, which is sin, has penetrated the world so deeply, and has so debilitated us, that we cannot uphold and practice consistently our highest ideals without that healing of mind and heart which is the gift of the Holy Spirit. Although a utopian state of dedicated humanism is theoretically possible, there is no historical evidence for its sustained, unselfish exercise in human history. Good will, passion, and feverish action do not suffice to preclude future calamities. The assumption that the world must be perfect is often combined with the assumption that all disorder derives from exploitation and sin, so that it becomes a moral and political virtue to hate what is disordered or imperfect since it must be caused by evil, which we must hate in its representatives. Such visions allow no room for human beings in their finiteness, in their history, in their smallness, in their failures.

The Christian vision of failure in the world order, and in the individuals who constitute it, is that of its Lord who has revealed to us what it means to be moved by the love of God and neighbor. His creative vision accepted the fact of an imperfect, fallible world of limited persons. He has embraced and elevated human finitude:

For it is not as if we had a high priest who was incapable of feeling our weakness with us; but we have one who has been tempted in every way that we are, through he is without sin. Let us be confident, then, in approaching the throne of grace, that we shall have mercy from him and find grace when we are in need of help (Heb 4:15-16).

The vision of Christ overcomes the human failure to believe that we have nothing beyond ourselves, that our own values are merely what we create for ourselves, that the social complexus of infinite relationships bear the ethical burden as substitute for the person. The vision of Christ comprehends the finitude of the human person and of human society. Christ, the compassionate high priest, “can sympathize with those who are ignorant or uncertain because he too lives in the limitations of weakness” (Heb 3:2). His vision counters that ideological perfectionist intolerance for allowing mistakes, that modern form of angelism which believes that this world can be paradise. It is embodied in the theological tradition where there is still room for those who hear the word, but fail to practice it. They are called, especially by themselves, “sinners,” and Christians are admonished to love them, too, somehow. This tradition counters the ideological mood where there no longer seems to be space for failures, where the problems confronting us are believed to be too vast, too pressing, to allow anyone the liberty to fail. It counters the ideologue’s self-righteous assumption that “the others” have a monopoly on human failure. Christianity affirms that all of us need our merciful God’s redemption because we all fail. It affirms the validity of finite persons who are created by something other than themselves.

Belief in God or Radical Self-Reliance?

Angry new atheists and agnostics who hate religion do not speak for all atheists and agnostics. Many atheists and agnostics affirm the value of religious faith in God. A Jewish agnostic friend affirms the value of belief in God on the basis of her religious friends who had the courage to face death: “Anything that gives persons the courage to face death is good.” Even the religiously-indifferent Napoleon promoted religion because it promoted civic friendship, peace, and morality.

The angry new atheists’ categorical claims that religion poisons everything is undermined by the common interpretation according to which God’s testing Abraham taught, among other things, that the then widespread practice of child-sacrifice was contrary to God’s will, and must be put to an end forever.

At the same time, Mr. Hitchens has nothing to say about the historical role of religion, particularly Christianity, in nourishing the soil in which our widely and deeply shared beliefs in liberty, democracy, and equality took root, and grew strong—a subject dealt with perceptively by Yale professor of computer science, David Gelernter, in his recent book, Americanism: The Fourth Great Western Religion.

Mr. Hitchens’ selective outrage over the crimes of allegedly religious individuals and societies contrasts with his apparent obliviousness to the twentieth-century atheist Soviet, Nazi, and Maoist exterminations that surpassed those of all previous centuries combined. Hitchens holds out the naïve utopian hope that eradicating religion will subdue humanity’s evil propensities, and resolve its enduring questions. He shows no awareness that his atheism, far from resulting from skeptical inquiry, is the rigidly dogmatic premise from which his inquiries proceed, and that it colors all his observations, and determines his conclusions.

The Judeo-Christian communities of faith believe that the origin, ground, and destiny of all creation is Goodness Itself; that human beings have the freedom to intelligently and responsibly use, or foolishly and irresponsibly abuse, the boundless gifts and goods of the Generous One; that we are free to be either humbly grateful, or obtusely indifferent, to the Generous One. If human freedom is genuine, and God really does give us autonomy when we are called into being, and if love is not coercive, we cannot unequivocally assert that everybody is going to behave a certain way. Grace is not a bulldozer that finally makes people do something, whether they are willing or not.

Insofar as we are the created effects of the Creator “effecting” us, we are the objects of God’s universal saving love. We are freely responding, positively or negatively, to the grace and call of our Origin, Ground, and Destiny. We do not exist independently of the Ultimate Reality, which we inevitably experience as the Question-Raising, and Question-Answering, Mystery at the heart of our lives, whether or not we have been enlightened by the historical biblical revelation. The quality of that experience is all of a piece with the quality of the conclusion of our life-long experience/process.

The revealed superstructure of human experience illuminates the primordial, preconceptual infrastructure of that experience. John’s Gospel tells us that persons recalcitrant to the grace and call of God within the infrastructure of their experience will be no less recalcitrant at the level of the revealed superstructure: No one recognizes Christ for what he is unless the Father draws him to that re-cognition, that “second knowing” or re-cognition of what one already knows in one’s primordial, non-conceptual/preconceptual experience. Christ has given his life/Holy Spirit for all human beings, independently of their knowing about it. That Spirit, we believe, is a “given” for every human life before and after Christ. Our free reaction to the “given” (grace and call of Christ’s Holy Spirit) determines whether or not we have accepted it, our new life in the Spirit of the Triune God.

Matthew’s Gospel (ch. 25) tells of the Son of Man arriving for the judgment, informing people that they had been in touch with him when they had shown compassion for him, even without recognizing him. Matthew’s text suggests an analogy. Imagine that you have a most enjoyable conversation with a stranger on your way to a lecture/film, only to discover to your astonishment that the individual whose company you had so much enjoyed is the one giving the lecture, or the star of the film. Matt. 25 implies that we shall have had experience of the Son of Man long before our realizing it, at the final judgment. Matt 25 assures us of our eventual “So-that-was-You!” knowledge of our historical experience! The experience is primordial, and prior to our knowledge of the One experienced! We had met the One in every one that we had experienced.

The Christian Experience and its Critics

Because human beings have an almost boundless capacity for self-deception, not all persons affirming that they are intelligent, moral, or religious are the intelligent, moral, or religious persons that they claim to be; nor, by the same token, not all persons who make no claims to being especially intelligent, moral, or religious, are lacking in these qualities. The gospel narratives about the clash between Jesus and the religious authorities underscore the dialectical differences in understanding what is genuinely religious, and what is pure sham. Both the religious authorities, and Jesus, accused one another of being the agents of Satan. In these clashes, Jesus affirmed the only objective basis for making such claims: by their fruits we shall know them. Intelligent, reasonable, and responsible decisions and actions proceed from intelligent, reasonable, and responsible persons. Stupid, unreasonable, and irresponsible decisions and actions proceed from stupid, unreasonable, and irresponsible persons.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, divine and human love is the distinctive character of an authentically religious life. We are called to love God above all, and to love others as ourselves. The Love that calls us into existence is a covenant-creating and covenant-sustaining Love experienced in the communion, community, and communication of the community of faith. The Ten Commandments express the imperative of divine love for an authentically human community, where loving God above all liberates us from the self-idolatry that would reduce the human community to a state of civil war, of homo homini lupus. Loving God above all is freedom for loving others as equals.

Jesus, recognized as the Incarnate Word of the God who is Love for the Christian community of faith, affirms that: “By this shall all know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). Mutual love enables knowledge of what is authentically religious: “By this all will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). Jesus reveals the befriending God who is known in the community of divine and human friendship: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13); “No longer do I call you servants…but I call you friends” (John 15:15 RSV).

The divine love that calls the community of faith into existence, and sustains its existence can be lost:

Whoever claims to be in light but hates his brother is still in darkness. Anyone who loves his brother remains in light and there is in him nothing to make him fall away” (1 John 2:9-10).

Although hatred of others renders specious any claim to being religious, self-rightness clearly enables such self-deception. Over the centuries, both the Jewish and Christian communities of faith have had to deal with the problem of their false prophets, the pseudo-religious, whose hatred and falsehood betrayed the true goodness of our loving God. Responsiveness to the love of God grounds the only legitimate claim to being authentically religious. Hearing the Word of God is always a question of living in response to the Word of Love.

Death: The Final End, or Prelude to the Resurrection?

Assuring us that we are advancing toward a world that will be made perfect by technology and science, the new atheists blame religion for genocide, injustice, persecution, backwardness, and intellectual and sexual repression. Theirs is both the illusion that, under the guise of science or rationalism, we can free ourselves from the limitations of human nature, and perfect the human species, and that we are morally advancing as a species, despite the fact that little scientific or historical evidence supports this idea. Individuals and societies are subject to both moral and cultural progress and decline. Our personal and collective histories alternate between periods of light, and periods of darkness. Individuals and societies not only develop, but also suffer breakdowns. We may advance materially without advancing morally. The belief in an ineluctable collective moral progress ignores the inherent fallibility of human nature, as well as the tragic reality of human history. The illusion that we can master our destiny, while ignoring the truth of our human condition, has serious consequences.

Without an ethic based on the truth of things, one that takes into account the limits and precariousness of the human situation, we cannot realistically begin to cope with our individual, social, and political problems. Our utopian schemes generally finish miserably.

The obscurantist, new atheists dismiss the religious impulse that addresses something just as real and concrete as the pursuit of scientific knowledge: the human hunger for the sacred, the transcendent, the mysterium tremendum et fascinans. God is, as Aquinas argues, the power that allows us to be ourselves. God is the call to marvel, wonder, and reverence. We are ingrained with this impulse which asks: What are we? Why are we here? What, if anything, are we supposed to do? What does it all mean? Science, while illuminating these questions, cannot answer them. Scientific laws cannot replace moral laws.

Our openness to the transcendent, inspires us to create myths and stories to explain who we are, where we came from, and our place in the cosmos. Myth is more than a primitive scientific theory that can be discarded in an industrialized age. We all stoke the fires of symbolic mythic narratives to give meaning, coherence, and purpose to our lives. The language of science is now used by many atheists to express the ancient longings for human perfectibility. According to them, science, rather than religion, is the way from paradise lost to paradise regained. The rationalists of the Enlightenment taught that the godless religion of scientific method could be applied to all aspects of human life, an application that would lead to a better world. They saw that the universe as ruled exclusively by consistent laws which could be explained mathematically or scientifically. Knowledge of these laws sufficed for understanding ourselves and our universe. The disparity between the rational person and the instinctive, irrational person would be solved through the education and scientific knowledge that would eradicate superstition and ignorance. Those who could not be educated and reformed, radical Enlightenment thinkers began to argue, should be eliminated so they could no long poison society. The Jacobins were among the first of the totalitarians who justified murder by invoking supposedly enlightened ideals. Their radical experiment in human engineering was embodied in the Republic of Virtue, and The Reign of Terror, which saw thousands executed. Belief in the moral superiority of Western civilization allowed colonial powers to exterminate people of “inferior races.”

The delusional dream of human perfectibility or salvation though science clashes with the religious realism of the community whose faith is grounded in an authentically religious conversion, responding to the grace and call of the transcendent Good, True, and Beautiful, for our ultimate happiness and fulfillment. Such personal transformation unfetters the mind and heart from prejudices that blunt reflection and self-criticism. If self-knowledge of individuals and societies is the beginning of wisdom, to know ourselves is to accept our limitations and imperfections.

Recent Comments