Fr. Aidan Nichols in his book, Christendom Awake, rightly points out that we have lost the cultural foundation of the spiritual life. In the modern world, God is perceived as absent and there is an intense focus on the individual. Nonetheless, he insightfully recognized the emergence of a new spirituality witnessed by the likes of St. Therese, Bl. Charles de Foucauld, and St. Edith Stein. He describes the spirituality of these new masters as follows: “Their prayer life appears to have arisen with a force and intensity unusual in the history of spirituality from out of a sense of what their very existence demanded. They could not take prayer for granted … They found out, rather, that for them existence was not bearable without prayer. Theirs was existential praying.”1 They had “to find God concretely, personally, in the spiritual desert of modern society.”2

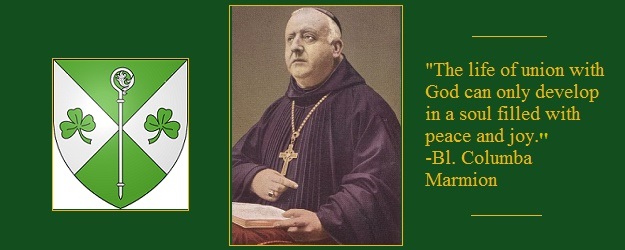

I would like to suggest that Bl. Columba Marmion likewise points us to a spirituality fit for the modern desert. His intense focus on our spiritual conformity to Christ, and the need to live out our adopted sonship, fit with Nichols insight on existential praying. Bl. Marmion advocates a spirituality of living in and through Christ that provides us with a profound and simple way forward in the midst of the spiritual and cultural crisis of our time.

Why Bl. Columba Marmion Matters

I would like to begin by laying out a few general reasons why Bl. Marmion is an important figure for our time. First of all, his spiritual teaching centers on Christ. To be holy is to be Christ in the world, to accept one’s spiritual life as essentially an extension of His own. This provides both the grandeur and simplicity of Marmion’s teaching: the grandeur as Christ’s life becomes our own; the simplicity as it is the one fundamental and necessary reality of the spirituality life.

Second, his teaching helps us to overcome the rupture between doctrine and spirituality, which unfortunately has become prevalent. He does so especially by rooting his spirituality in a strong Christology with a focus on the Trinity. He has a remarkable gift to communicate clearly the most profound and difficult of dogmas.

Third, the “Little Way” has become popular through St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s Story of a Soul. St. Thérèse spoke of the Way of Love: doing all things, even the simplest with great love. Marmion, however, provides both the deep theological foundation for this teaching by reflecting on the divine childhood, and helps us to apply it. Marmion’s application of the Little Way in his spiritual direction is simple, direct, and profound.

Fourth, he is a translator of Benedictine spirituality for our time. Benedictines have more Saints and Doctors of the Church than any other order. The number of saints begins to thin out in the latter part of the Middle Ages, and dries up almost altogether in the modern period, apart from the martyrs of the Reformation and French Revolution. Marmion, along with the great voices of Solesmes, is a crucial figure for continuing the Benedictine tradition, and translating its spiritual vision for our time. We can also see him updating this vision with a fuller view of the mystics, as he draws often upon the Carmelites, St. Francis de Sales, and Catherine of Sienna.

Fifth, although Marmion entered Benedictine monasticism, the personal choice of his religious name, Columba, hearkens back to the great Celtic monastic tradition of his Irish homeland. By leaving Ireland for the Continent (as a monk in Belgium), he continued the Celtic tradition of peregrination pro Christo. This lifelong pilgrimage, or even exile, bore fruit in Marmion’s reach through the British Isles and Europe as both an English and French language retreat master.

Sixth, although Marmion has been somewhat forgotten in recent time, it is important to remember that his books were bestsellers, and were translated into about a dozen languages. As a retreat master, he was in high demand, and was even a confessor to Belgium’s Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier. Many popes have endorsed his writing, and Pope Benedict XV kept his book, Christ the Life of the Soul, on his nightstand. Truly, Marmion was a great spiritual teacher of the Church in the early twentieth century.

I would summarize Marmion’s style and influence generally as follows: St. Thomas Aquinas meets St. Therese, who meets St. Benedict. In Marmion, we have our great speculative theologian and dogmatic mystic; we have a practical exposition of the little way of love, applied through retreats and letters of spiritual direction; we have a great leader of souls, an abbot who communicates the genius of the liturgical and monastic life to a broad audience.

St. John Paul II, during Marmion’s beatification in the Jubilee Year 2000, summarizes his spiritual vision well: “in his writings, he teaches a simple yet demanding way of holiness for all the faithful, whom God has destined in love to be his adopted children through Jesus Christ (cf. Eph 1: 5). Jesus Christ, our Redeemer, and the source of all grace, is the center of our spiritual life, our model of holiness.”3

A Brief Overview of Bl. Marmion’s Life4

Bl. Marmion was born in Dublin in 1858 to an Irish father and French mother (though he did not learn to speak French proficiently in youth). He was given the name Joseph, taking Columba only upon entering religious life. After a pious upbringing, he became a seminarian, and was sent to Rome to reside at the Pontifical Irish College. A visit to Monte Cassino began a dream of becoming a Benedictine missionary to the Pacific, but he also encountered the Benedictine Abbey of Maredsous in French-speaking Belgium on his travels back and forth from Ireland. His bishop, the Cardinal Archbishop of Dublin, was not receptive initially to his Benedictine vocation, and he was ordained a diocesan priest in 1881.

However, in July of this same year, another trip to Maredsous proved decisive. During his stay, he heard a voice: “It is here I want you.” It would take some time for this to come true, as Marmion began his priestly life outside of Dublin working in parish life, hospital ministry, as a chaplain to sisters, and as a seminary philosophy professor. Eventually, he did receive the necessary permission and entered Maredsous in November of 1886, taking the name Columba.

Entering monastic life as a diocesan priest was not easy, and Marmion had a difficult novitiate, even to the point of calling it traumatic. Having to learn French did not help. It did not take too long for him to acclimate, though, and after his solemn profession in 1891, he was even chosen as an assistant novice master. In 1899, he assisted in establishing a new foundation at Mont-César in Louvain, serving as Prior. His time at Mont-César was significant: he resumed teaching as a professor of theology, beginning to give his famous retreats, and formed a lifelong friendship with Cardinal Mercier.

When Maredsous’s Abbot, Dom Hildebrand de Hemptinn, relinquished his role at the Abbey to focus exclusively on his position as Abbot Primate of the Benedictines in 1909, Marmion was called back to become the next abbot. During his time as abbot, he became known internationally as a spiritual director and retreat master. His famous trilogy of books (more on them below) grew out of the notes from his retreats. He had a high profile, serving as confessor to Cardinal Mercier, advisor to Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, and his spiritual writing reached even to Pope Benedict XV.

The great trial of Maredsous during Marmion’s life came during World War I, as Belgium took the brunt of the brutalities of the war. To avoid having his young monks enter the draft, he travelled in disguise as a cattle dealer to the British Isles, where he managed to establish a temporary foundation in Ireland. After the war, he helped established a new Belgian Congregation of Benedictine monasteries, disentangling them from German monasteries on the other side of the war. In the midst of the after-effects of the war, he also temporarily oversaw the Monastery of the Dormition in Jerusalem, before it was transferred back to the Beuron Congregation.

Marmion died on January 30th during the flu epidemic of 1923. When he was exhumed in 1963, his body was found to be incorrupt. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II during the Jubilee of 2000, and in 2009, the Archdiocese of Vancouver opened a canonical investigation into a possible second miracle to advance his cause for canonization.5

Bl. Marmion’s Trilogy

Bl. Marmion published three major works during his life, known as his trilogy, edited by his secretary, Dom Raymond Thibaut, from his retreat notes. The works and original publication dates are Christ the Life of the Soul (1917), Christ in His Mysteries (1919), Christ the Life of the Monk (1922). Thibaut continued to edit Marmion’s retreat notes after his death, and came out with anthologies, as well as new works, such as Sponsa Verbi (1925) on the religious life, Christ the Life of the Priest (1951), and Union with God (1949), comprised of selections of his letters of spiritual direction.

The trilogy focuses on the unfolding of Marmion’s central teaching on divine sonship. It begins with a general treatment of how our life comes from our union with Christ, then details how we access the mysteries of the life of Christ, through the liturgy and sacraments, and ends with an application of his teaching through the Benedictine life.

The Center of His Teaching—Christ, the Life of the Soul

Marmion never tires of repeating the central thesis of his spiritual teaching: Christ is the life of our soul. To accept this, we have to move away from our own ideas of holiness, of our own plans, and accept God’s plan to give us holiness, in and through Christ, who is the “source” and “dispenser” of holiness. Marmion states:

All holiness … will consist of receiving the divine life from Christ and through Christ, who possesses the fullness of it and who is established as our only Mediator; of preserving it, of increasing it constantly by an adhesion ever more perfect, a union ever more close, to Him who is at its source. Holiness, then, is a mystery of the divine life communicated and received.6

The Father communicates His divine life to the Son, who in turn communicates it to us through the Incarnation.

Marmion relates that a central point of our reception of God’s divine life stems from our adoption as sons in the Son. We see adoption and childhood at the very center of all of his writing and teaching. God has chosen us, and drawn us into his divine life through Baptism. The Christian life is the living out of the gift of grace of adoption and entrance into the life of the Trinity. “We shall understand nothing—I do not say only of perfection, of holiness, but even of simple Christianity—if we do not grasp that its most essential foundation is constituted by the state of a child of God; participation, through sanctifying grace, in the eternal Sonship of the Word Incarnate.”7 Through our union with Christ, we enter into the life of the Trinity.

To be holy is to be like God. Holiness is a supernatural life that only He can give, and with which we must cooperate. Our participation in God’s life is Trinitarian. “Our holiness will be to adhere to God known and loved, not any longer simply as the author of creation but as He knows and loves Himself in the bliss of His Trinity.”8 We do not become holy through our own efforts, but by “sharing {God’s} inner life.”

Such a short summary cannot do justice to a large work of theological depth, but at least it provides an entry point to Marmion’s central thesis.

How Christ is the Life our Soul—Christ in His Mysteries

In his epistle to the Ephesians, St. Paul describes how “by reading what I have written, you can recognize the understanding I have of the mystery of Christ” (Eph 3:4). Further, Paul says “this grace was given: both to announce to the Gentiles the unfathomable riches of Christ, and to enlighten all men about the dispensation of the mystery which has been in God before all time began” (Eph 3:8-9).9 What is the mystery of which Paul speaks? Paraphrasing Paul, Marmion describes it as “Nothing but Christ, and Christ crucified.”10 The Incarnation, God’s entrance into the world, is the great mystery God prepared before the creation of the world.

If Christ is the great mystery made known to us, why then does Marmion refer to mysteries in the plural? Marmion describes that the “mysteries of Jesus are states of His sacred humanity,” and “each one of his mysteries is a revelation of His virtues.”11 The mysteries of the life of Christ reveal to us, in their own way, the mystery of Christ. The contemplation of these mysteries, in Scripture and through the liturgy, provide us access to these mysteries so that we can mystically conform ourselves to Christ.

The mysteries, then, are not theoretical, but opportunities to conform to Christ, the goal of Marmion’s spirituality. “The more we know Christ,” he says, “the more deeply we fathom the mysteries of His Person, and of His life, the more we prayerfully study the circumstances and details that Revelation has confided in us—the more, also, our piety be true, and our holiness has solidity.”12 We cannot take in the mystery of Christ as a whole, which is why He reveals Himself through the multitude of His mysteries: “We shall see that each one of His mysteries contains its own teaching, brings its special life; is for our souls the source of a particular grace, the object of which is to ‘form Jesus in us.’”13

Not only do we learn about Christ through His mysteries, but due to our conformity to Christ, they mark out for us the stages of our own spiritual journey. Marmion says that we actually need to enter into them. The mysteries of Christ “conform our lives to this model,” by drawing us into their reality. “What a feast, how satisfying and joyful it is … to look at the divine actions, to enter into their mystery in order to drink, as at a spring there, the very life of God.”14 The mysteries of Christ provide the means by which we enter into God’s life. We are conformed not only to the humanity of Christ, but even to His divinity through the mysteries: “This is why our imitation of Christ should extend not only to his human virtues, but also to his divine being.”15

In Baptism, we become members of Christ’s Body, sharing completely in His life. Therefore, the mysteries of Christ are not only His, but also become our own possession. Marmion describes this reality at length:

The mysteries of Christ are ours; the union that Jesus Christ wishes to contract with us is one in which everything He has becomes ours. With a divine liberality, He wants us to share in the inexhaustible graces of salvation and sanctification that He has merited for us by each of His mysteries, so as to communicate to us the spirit of His states and thus to bring about in each of us a resemblance to Him—the infallible pledge of our destiny planned from eternity. Christ has passed through diverse states; He has been a child, an adolescent, a teacher of the truth, a victim on the cross, glorious in His resurrection and ascension. By thus going through all the successive stages of His earthly existence, He has sanctified the whole of human life.16

The mysteries of Christ “are ours as much as they are His” because even when they were first accomplished, He “lived them for us.”17

Further, the mysteries are living realties, not simply bound to the past: “It is true that in their historical, material duration the mysteries of Christ’s life on earth are now past; but their power remains, and the grace that allows us to share in them operates always.”18 This is why we celebrate the mysteries in the liturgy; not just to remember, but to participate in the grace that emanates from them. Marmion describes how “it is especially in the liturgy that the Church educates, brings to maturity, the souls of her children so as to make them resemble Jesus and, thus, to perfect in them that copy or ‘image’ of Christ which is the very shape of our planned destiny.”19 Liturgy and the sacraments provide us access to the mysteries of Christ, and mystically conform us to Him. Through the mysteries of Christ, Marmion describes how divine sonship becomes a living reality within the soul.

How We Live Out the Life of Christ in our Souls—Christ the Life of the Monk

Marmion’s writing on the monastic life follows the same principle as His previous works. Christ is our exemplar: “He came on earth to be our model” the “ideal of our souls”20 Marmion extends this principle to one particular way of life, which more intensely embodies the conformity to the exemplar. St. Benedict’s Rule provides a general model for this conformity. Marmion remarks immediately that, in essence, the monastic life does not differ from the vocation of every Christian: “When we examine the Rule of St. Benedict, we see very clearly that he presents it only as an abridgement of Christianity, and a means of practicing the Christian Life in its fullness and perfection.”21 Benedict’s vision for the Rule contains the essence of Christian life: “To seek God constitutes the whole program; to find God and remain habitually united to Him by the bonds of faith and love, in this lies all perfection.”22

It should not be surprising that Marmion’s roots his explanation of the Rule in his core theological vision of sharing Christ’s life. The monk seeks God by imitating Christ: “In this seeking after God, the principle of our holiness, we cannot find a better model than Christ Jesus himself.”23 Our perfection is rooted so profoundly in Christ that Marmion says that we have only “a borrowed perfection” as Christ admits us to share in his own beatitude in the life of the Trinity.24 The goal of the Christian life is Christ, to follow Him ad Patrem (to the Father).25 Monasticism pursues this common goal, only more intensely.

For Marmion, the monastic life is only an intensification of the general call to follow Christ issued by the Gospels. He uses the word “intense” (or related words) over 40 times in the work. Here is one example: “Let us then live the life of faith as intensely as we can with Christ’s grace: let our whole existence be, as our great Patriarch would have it to be, deeply impregnated, even in the least details, with the spirit of faith, the supernatural spirit.”26 And further: “The monk seeks to bring to realization the fullness of the Christian life; he must possess within himself a deeper degree of ‘death’ but also a more powerful intensity of ‘life’ than is the case with the ordinary faithful.”27

Not only does the monastery reflect the vocation of each Christian, it also bears relation to the whole Church. The monastery embodies as a microcosm the society which Christ founded in the Church, with the abbot holding the place of Christ. “To this society, St. Benedict gives an organization modeled upon that which the Word Incarnate has chosen for His Church.”28 The life of this society, moreover, should have a “family character.”29 The monastery lives as a family under the care of a father (abbot), because it follows the pattern established by Christ: “Moreover, this form of government is traced upon that which Christ Himself, Eternal Wisdom, has given to His Church.”30 The embrace of this model is one further way of conforming to Christ.

The outward conformity of community life is fed at its core by an interior conformity. Obedience to the abbot follows Christ’s own obedience to the Father. The monastic life constitutes one particular way of offering ourselves, with Christ, to the Father. The monastic profession embodies conformity to Christ’s offering of Himself on the Cross: “Monastic Profession is indeed an immolation, and this immolation derives all its value from its union with Christ’s holocaust.”31 Every Christian is called to such a conformity, but the monastic vows guide the monk to embrace a particularly intense form. The goal, like the Christian life in general, is the reproduction of Christ in the soul. What differs in Marmion’s monastic writings from his more general reflections is the concreteness of the method of imitating of Christ.

Marmion describes the imitation of Christ not just as following His outward actions, but in terms of a reshaping or refashioning from the inside. The monastic life becomes a work of art, as “art consists in giving a faithful material reproduction of an idea, of an ideal.”32 The “Man-God” is the ideal, of course, and “God’s great desire is that we should resemble His Son, Jesus, as perfectly as possible. Therefore, the whole method of the spiritual art consists in keeping the eyes of the soul unceasingly fixed upon Christ, our Model, this humano-divine Ideal, in order to reproduce His features in us.”33 In the art of the monastic life, God is the artist, and Benedict’s Rule provides the tools by which the Patriarch “wishes to develop his monks.”34

Marmion as Spiritual Director

Every Christian, not just the monk, is called to receive a reproduction of Christ in his or her soul, finding the right means of making a self-immolation or offering. We see this reality expressed in Marmion’s letters of spiritual direction, which Dom Thibaut gathered in selected form within the work, Union with God. In this text, we see Bl. Marmion’s amazing ability to direct a Cardinal, priests, and religious from other orders, his own monks, and the laity. His directives are simple and accessible, yet also firm and demanding.

We see Marmion’s fatherly affection and care, as he imparts his great spiritual insight:

Indeed, my daughter, the inner life becomes very simple from the moment we understand that it consists entirely in losing oneself in Jesus Christ, making only one heart, one soul, one will with His own. This is not done once and for all, “one buries oneself more and more in this holy will” as Saint Chantal so truly said.35

Holiness is a matter of growth and development. The laity also need the application of the art of the spiritual life to be refashioned according to the ideal. In applying his spiritual art, Marmion provides very practical suggestions. He guides on how to begin the day: “Regularity and fidelity in rising in the morning are of capital importance … It is a question of giving the first moments of the day to Our Lord or to His enemy, and the whole day bears the reflection of this first choice.”36 He also gives advice to a mother:

God does not ask a married woman of the world for the austerities and mortifications that may be practiced by those living in the cloister. But He sends them other trials adapted to their state and which render them so agreeable to His Divine Majesty. Our Lord asks of you: 1. To accept daily the sufferings, the duties, and the joys He sends you, as Jesus accepted all that came to Him from His Father… 2. The perfect fulfillment of your duties: a) Towards God … above all family prayers; b) Towards your neighbor—Towards your husband…Towards your children. The grace of motherhood has its origin in the Heart of God, and He puts it in the mother’s heart in order that she may love and guide her children according to the Divine good pleasure … c) Towards yourself…. Be joyful and gay, natural and straightforward as you are, and God will bless you.37

Marmion applies his vision of conformity to Christ to the circumstances of life in the world.

Conclusion

Bl. Columba Marmion has translated the great Benedictine, spiritual vision into our own times. He lays out the fundamental thesis that Christ is the essence of our spiritual life. He then makes clear the liturgy’s role in shaping our life according to the mysteries of Christ. Finally, we see this vision applied to concrete expression, both in the monastery, and spiritual direction. Marmion’s vision can form us theologically, spiritually, and even practically in how we order our lives. He guides us in living in Christ, in allowing Him to be our life, our living water in the midst of the desert of the modern world.

- Aidan Nichols, O.P., “Resituating Modern Spirituality,” in Christendom Awake: On Reenergizing the Church in Culture (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999), 203. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pope St. John Paul II, Homily for the Beatification of Pius IX, Tommaso Reggio, William Chaminade, and Columba Marmion (Sep. 3, 2000). ↩

- I draw these details mainly from two sources: Mark Tierney, O.S.B., Blessed Columba Marmion: A Short Biography (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000); The English Letters of Abbot Marmion: 1858-1923 (Baltimore: Helicon Press, 1962). ↩

- Gerry Bellett, “Healed by Monk’s Divine Intervention?,” Vancouver Sun (July 11, 2009). ↩

- Bl. Columba Marmion, Christ the Life of the Soul, trans. Alan Bancroft (Bethesda, MD: Zaccheus Press, 2009), 8. Italics original. ↩

- Marmion, Christ in His Mysteries, 64. ↩

- Marmion, Christ the Life of the Soul, 18. ↩

- See Marmion, Christ in His Mysteries, 3. ↩

- Marmion, Christ in His Mysteries, 5. ↩

- Ibid., 29; 15. ↩

- Ibid., 10. ↩

- Ibid., 12. ↩

- Ibid. 11. ↩

- Ibid., 52. ↩

- Ibid., 41. ↩

- Ibid., 12; 13. ↩

- Ibid., 20. ↩

- Ibid., 26. ↩

- Ibid., 14. ↩

- Dom Columba Marmion, O.S.B, Christ the Ideal of the Monk: Spiritual Conferences on the Monastic and Religious Life (St. Louis, Mo: B. Herder, 1926), 1. ↩

- Ibid., 3. ↩

- Ibid., 15. ↩

- Ibid., 19. ↩

- See ibid., 252. ↩

- Ibid., 105. ↩

- Ibid., 125. ↩

- Ibid., 68. ↩

- Ibid., 65. ↩

- Ibid., 66. ↩

- Ibid., 108. ↩

- Ibid., 123. ↩

- Ibid., 124. ↩

- Ibid., 125. ↩

- Union with God: Letters of Spiritual Direction by Blessed Columba Marmion, ed. Dom Raymond Thibaut, trans. Mother Mary St. Thomas (Bethesda, MD: Zaccheus Press, 2006), 33. ↩

- Ibid., 24. ↩

- Ibid., 44-45. ↩

I would simply like to point out a far simpler spirituality, that of love…..Jesus gave very few commandments, and quoted #1 of love of God with ALL of our being, since following the #2 commandment of love of others is totally contigent upon the first.

by loving God, simply loving God, with our entire being over any other thing, be that thought, feeling, created things, our own spiritual enrichment, ANY thing, we become capable of fulfilling all the failures in the history of scripture, and truly becoming followers of the Christ, and more Christ-like, as we are transformed from within, by giving God a chance to do the work.

only then do we truly become tapped into that inexhaustible wellspring of eternal love which loves all of creation into existence each and every moment, upholding it, and us, with that attentive love, which if withdrawn would be a collapse of everything into beyond nothingness…

a very good primer on the subject of spirituality and its necessity to being a true follower of Christ in self-less love is the very short and delightful “Common Mystic Prayer”, by Fr Gabriel Diefenbach OFM Cap, written in the late 1940s, and its bibliogrqphy of little know spiritual classics is worth its weight in gold all alone.

A far weighter step by step how-to manual is the work often quoted by Fr Gabriel, “Sancta Sophia” or “Holy Wisdom”, which is a pious workbook of rooting out all elements of self in order to allow only God to work in our lives.

Both works draw heavily upon both St John of the Cross, and St Teresa of Avila, and truly help point out exactly what these two great Saints were pointing us towards….

Very sorry for cell phone typos and omission of the author of Sancta Sophia, who is Fr Augustine Baker OSB, the work published in the early 1600s as assembled from his conferences with the convent nuns of whom he was spiritual director.