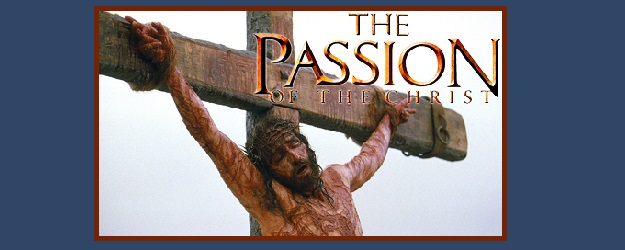

The photo is from The Passion of the Christ, a 2004 American biblical

drama directed by Mel Gibson, written by Gibson and Benedict Fitzgerald,

and starring Jim Caviezel as Jesus Christ.

I just finished watching, for a third time, the movie: The Passion of the Christ. After this latest viewing, I was deeply moved by the particular scenes involving Christ and the cross: the wooden beams he was made to carry; the wooden beams He was nailed to; the wooden beams He stained with his blood; the wooden beams from which He gave us His seven last word; and the wooden beams He would die on from blood loss and asphyxiation.

While reflecting upon the importance of those wooden beams, I was drawn to the Person of Christ as the fulfillment of so many great events in salvation history, and the different “woods” of God, the Master Carpenter (cf. Job: 38: 4-7). Consider:

- In the case of Adam, we have the apple hanging from the wooden branch (cf. Gn.3:1-5);

- In the case of Noah, we have the ark built from gopher wood (cf. Gn.6:14);

- In the case of Abraham, we have the wood that Isaac would carry up Mount Moriah as kindling for the burnt offering (cf. Gn.22:1-19);

- In the case of Moses, we have as part of the Passover prescription, the wooden door posts and lintel that would be stained with the blood of the lamb (cf. Ex.12:7) (cf. Ex.21:6; Deut.15:17 for tradition that points to these being wooden posts);

- In the case of David, we have the Ark of the Covenant made of acacia wood (cf. Ex.25:10) that would be carried to Jerusalem;

- In the great prophecy of Isaiah on the coming of the Messiah, we have the imagery of a branch shooting out from the roots of the stump of Jesse, and that the Spirit of God will rest upon him (cf. Is.11:1-11);

Just as wood was used to build the ark that would protect and carry the household of Noah safely through the waters of the flood, so are we to drink from the “spring of water welling up to eternal life” (Jn.4:14) that pours out from the side of Christ on the cross. Just as Isaac carried wood on his back up a mountain, so Christ, the new Isaac, carried wood up Golgotha as an obedient response to His Father. Just as the Israelite faithful stained the horizontal and vertical wood beams with the blood of the lamb, so does Christ—the new “lamb of God” (Jn.1:36)—stain the horizontal and vertical beams of wood on the cross. Just as David would carry the wooden ark that held the presence of God into Jerusalem, so Jerusalem would be the definitive place where we go to behold the presence of God on the cross in the Passion and death of Christ.

In regards to the prophecy of Isaiah, the word “Nazareth” comes from a Hebrew root meaning “branch.” Christ is the “branch” shooting forth from the line of Jesse.

Collectively, wood in salvation history has always pointed to death and life: where a branch, gopher wood, kindling, doorposts, and acacia wood would all play unsuspecting parts in the drama of God’s love affair with man, pointing towards a final crescendo in Christ’s death on the wood of the cross.

Wood, no doubt, has left its impression on the canvas of salvation history. It is fitting that God would use the very thing that was the instrumental cause in the loss of grace (apple hanging from a branch), to be the instrument used in the restoration of grace (cf. Rom.5:14).

The irony is rich, the Carpenter of the world who, in becoming man, learns the human trade of carpentry, finds himself renewing the world from the wood of the cross—WOW! The symbol of the cross that always signified death in Roman antiquity now has a corpus that signifies life, and history has forever changed because of it.

We read from the Office of Readings, Week 1, Ant. 1, in Ordinary Time: “See how the cross of Christ stands revealed as the tree of life.” The wood of the cross, once alive, growing and strong, itself dies, only to be used by the Master Carpenter, to bring us to the fullness of life beyond telling.

And what of our individual splinters?

Every cross we bear is difficult, often excruciating. Interestingly, the word excruciating comes from the Latin ex-cruces, which literally means “from the cross.” So the word we use to explain our most intense pain and agony is derived from the anguish and torture that comes “from the cross.” Christ now hangs on this cross, and gives it redemptive meaning. It could be said that what is most excruciating in each of our lives is what Christ gives to us “from the cross.” For most of us, this point is difficult to hear (it is for me… even as I write it), but we ought to remember what Saint Paul rejoices over in his letter to the Colossians: “Now, I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the Church” (Col.1:24).1 This verse from Saint Paul sets up the Church’s foundational teaching on redemptive suffering, which the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) expands upon: “By the grace of this sacrament (Anointing of the Sick), the sick person receives the strength and the gift of uniting himself more closely to Christ’s Passion: in a certain way, he is consecrated to bear fruit by configuration to the Savior’s redemptive Passion. Suffering, a consequence of original sin, acquires a new meaning; it becomes a participation in the saving work of Jesus” (CCC, 1521).

Consequently, in the light of Christ’s excruciating anguish and torture (and let us never domesticate the horror of the crucifixion), suffering acquires “new meaning”—redemptive meaning, and power. And as both Saint Paul and the CCC highlight, we share in this redemptive mission and power by conforming our suffering to Christ, and at once, offer this suffering to the Father.

It is one thing to write about redemptive suffering, and another to actually unite the splinters from the wood of our crosses to the Cross of Christ. We often protest (I included): “no one can possibly understand what I am going through.” In my own inquiry into suffering, I turned to the writings of Pope John Paul II for answers. It was then that I came across paragraph 26 of Salvifici Doloris, an Apostolic Letter “On the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering.” He writes:

In general, it can be said that almost always the individual enters suffering with a typically human protest and with the question: “why?” He asks the meaning of his suffering, and seeks an answer to this question on the human level. Certainly, he often puts this question to God, and to Christ. Furthermore, he cannot help noticing that the one to whom he puts the question is himself suffering, and wishes to answer him from the Cross, from the heart of his own suffering. Nevertheless, it often takes time, even a long time, for this answer to begin to be interiorly perceived. For Christ does not answer directly, and he does not answer in the abstract this human questioning about the meaning of suffering. Man hears Christ’s saving answer as he himself gradually becomes a sharer in the sufferings of Christ.

The answer which comes through this sharing, by way of the interior encounter with the Master, is in itself something more than the mere abstract answer to the question about the meaning of suffering. For it is above all a call. It is a vocation. Christ does not explain in the abstract the reasons for suffering, but before all else he says: “Follow me!” Come! Take part through your suffering in this work of saving the world, a salvation achieved through my suffering! Through my Cross. Gradually, as the individual takes up his cross, spiritually uniting himself to the Cross of Christ, the salvific meaning of suffering is revealed before him. He does not discover this meaning at his own human level, but at the level of the suffering of Christ. At the same time, however, from this level of Christ, the salvific meaning of suffering descends to man’s level and becomes, in a sense, the individual’s personal response. It is then that man finds in his suffering interior peace, and even spiritual joy.

As we reflect upon the words of (now a saint) John Paul II, we ought to reflect upon four overarching truths:

- First, there is Someone who does understand, and His name is Jesus Christ. Again, there really was a man who entered into history approximately two thousand years ago, who was crucified for our sins. Consequently, in the gift of faith, we could never say “no one understands what I am going through,” because there is not any kind of suffering that He has not already endured and conquered for our sake.

- Second, once we understand that He understands, we are to “follow Him,” uniting our splinters to the wood of the Cross. This following entails trusting God, which is the most concrete act and virtue of faith. Faith is first a gift, and second, an act, an entrustment of one’s whole life journey to God (which always includes pain and suffering).

- Third, we are to understand this journey to be one that is “gradual.” In other words, we need to be patient with ourselves, and confident in God, that He will, in fact, steadily reveal the dynamism behind our suffering when it is united to Christ on the cross. There is always the temptation to have everything understood in the here and now, but this is never how God reveals Himself. He always meets us how He made us and walks with us as He is. God is a true Gentleman!

- Lastly, this is a personal vocation. There is no one individual whose personal journey of faith is like another. In other words, there is a concreteness and particularity to every baptized Christian, and their walk with God. We might be tempted to compare our suffering with another person, and wonder why we got the short end of the stick, so to speak. But as Pope John Paul II reminded us, it doesn’t work that way. As Saint Teresa of Avila once put it: “God permits all things for the purposes of salvation.” Essentially, we have been called to encounter Christ in the interior life, the zone where mystery is revealed, and like Christ, with arms outstretched, offering our very unique suffering to the Father.

In the end, the Master Carpenter wishes to build us into His image and likeness, and we do this when we unite ourselves to the one thing that stands above every other thing: the corpus on the wood of the cross.

- The phrase “what is lacking” is never to be interpreted to mean “the suffering of Christ was not sufficient for redemption, and the suffering of the saints must be added to complete it…what is lacking then pertains to the afflictions of the entire Church, to which Paul adds his own amount” (Ignatius Catholic Study Bible. Edited by Hahn, Scott and Minch, Curtis. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2011), 326. ↩

Recent Comments