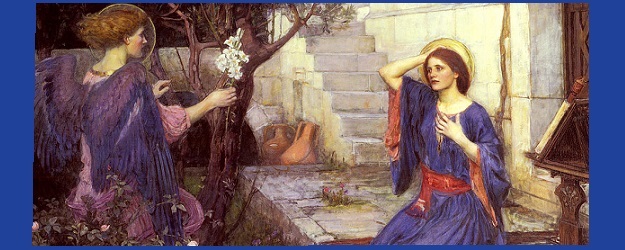

The Annunciation by John William Waterhouse, 1914.

Introduction

What is the difference between a furrow and a rut? A furrow is an intentional emptiness cut into the earth in preparation for fullness. A farmer’s plow intentionally cuts a furrow, opening the earth to produce a full harvest. A rut, however, is a haphazard wound in the earth caused by the repeated action of erosion. Wheels or water might cause this heedless wounding of the earth, but unlike a furrow, a rut is always barren. Thus, although both rut and furrow are open wounds upon the earth, a rut is unplanned erosion, resulting in sterility; while a furrow is intentional emptiness, awaiting fertility.

Like a rut, vice is the repetition of sinful actions that wear us down, and leave us barren. Virtue, however, is the repetitive restraint in the use of all sensible things, so that we are always empty enough to be open to spiritual things. Vice repeats sensual pleasure until it becomes purposeless. Any pleasure used without measure eventually becomes repetitive, dull and pointless. Therefore, we must escalate with wilder, riskier, pleasures to provoke the previous peak experience. However, each new gratification eventually also becomes dull and pointless, which drives us to start the same cycle all over again. Such desperate repetition of sinful actions erodes our spirit, wears us down, and leaves us barren. And that means we’re in a rut.

How do we get out of the rut of vice? We’ll be looking to the Blessed Virgin Mary’s virtues to answer precisely that question. We’ll glean those virtues by pondering God’s Word in our hearts, just as she did. And we’ll learn that while vice makes a tyrannical idol of the sensual, virtue opens the sensual to reveal the spiritual. Virtue, like a furrow, is intentional emptiness; by creating that intentional openness in our human nature, virtue prepares the sensual in us so that Jesus may disclose the spiritual to us. Thus, the spiritual and the sensual are not incompatible. The seed is spiritual, like the Word spoken by Archangel Gabriel; and soil is sensual, like the womb of the Virgin. Cooperating with each other, through our fiat, is fruitful.

We cooperate by carrying our cross with Christ, whose wounds are not ruts, but furrows. Cooperating with grace is virtue’s embrace of Christ’s wounds. Virtue opens our wounds to the wounds of Christ in an eternal embrace of the spiritual and the sensual—our wounded heart to His pierced Heart—so that the effusion of Jesus’ blood shed for us becomes an infusion of His grace into us. Just as the Cross was sunk into a barren rut, but became the tree of life, so we who sink into the rut of sin rise again by opening our wounds to the saving wounds of Christ.

Hence, the difference between vice and virtue is the same difference between a rut and a furrow. Like a rut, vice is the thoughtless repetition of consumptive actions that erode our spirit, wear us down, and leave us barren. Virtue, however, is a furrow: An intentional emptiness faithfully awaiting fulfillment.

Mary’s emptiness had a purpose, namely, to allow God to fill her with grace, and give birth to God, who always wants to be with us. Therefore, Mary demonstrates the wise self-restraint of the sensual, which disposes us to be open, or receptive, to the spiritual. Vice, however, so fills us with the sensual that we are enclosed within the sensible, and insensate to the spiritual.

Virtue disposes us to receive the spiritual, disclosed in the sensual, especially through the sacramental. Remember, however, that when filled to replete with the sensual, we are no longer receptive to the spiritual. The things of the earth are good, but if we are completely filled by them, then we are no longer empty, or open, to the even greater things beyond the earth to which all good things point. Vice is the thoughtless consumption, the mindless repetition of actions, that fill us to the point that we are unreceptive towards the Giver of all good gifts.

Thus, I offer to my fellow priests (and others) the following seven meditations on the virtues of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Three are included in Part I, and the other four contained in Part II, which will follow in the next edition of HPR. Each begins with a suggested Scriptural passage to ponder, and concludes with questions for either quiet meditation, or to share in priest support groups, and spiritual direction.

I wish I could say that I practice everything here that I write! Because I don’t, I close by asking those who meditate on these virtues of the Virgin, to please pray for me. And I will pray to my own patroness, Mary, Consoler of the Afflicted, to bless each of you.

Humility: Matthew 12: 46-50

There is a story that Cardinal Dolan of New York tells about himself. He says that after he was created cardinal, he and his father were ushered out of the glittering cathedral amid press and priests and prelates, when a reporter startled his dad first by flashing a photograph, and then almost gagging him with a microphone while shouting: “You must be very proud of your son.” Mr. Dolan rubbed his jaw and responded, “Which one?” Cardinal Dolan concludes that anyone who’s changed your diaper, isn’t much impressed with your mitre.

Like a diaper change, humility roots us in reality. No matter how talented we are, no matter how much attention is lavished upon us, no matter how much we are either complimented or condemned, if we are grounded in the earthy reality of our own messy humanity, we’ll always be true to ourselves and our roots.

Marvel at Mary. An archangel proclaims her the mother of the Savior. Then Gabriel makes her a prophet of the pregnancy of elderly Elizabeth. But neither the title “prophet of the almighty” nor “mother of the Savior” made her strut or swagger. She didn’t prance and preen, bluster or brag, although if anyone ever had reason to whoop it up, it was this lady conceived without sin, rushing to be kind to her kin. Remember, the angel never told Mary she should help Elizabeth; he didn’t have to. Like changing diapers, rushing to be a midwife to her kin was just what Galilean girls did. Because she was humbly rooted in reality, Mary was the same after the Annunciation, as before it. Her peasant feet were always firmly planted on the earth of Israel. She did not deny the great favors visited upon her; she did not worry about unwanted attention fixed upon her; and she did not swoon with artificial amazement when her blessedness preceded her.

Mary is the model of humility because she is rooted in all of her reality. When her reality rocks, she rejoices. And when her reality aches, she accepts. Through good times and bad, in sickness and in health, Mary always follows God through any reality, just as water always follows gravity.

The whole history of Mary is her finding God in all of her reality. When Mary was young, she was selected by angels, sought by magi, and serenaded by shepherds. And when Mary was old, she loitered with lepers, and bumbled with the blind, as they followed Jesus through hill and dale, chill and smell. Her humility was her flexibility in finding God in all of her reality.

Thus, when Jesus said: “Who is my mother? The one who does the will of God is my mother.” Mary accepted this new reality, where she had to decrease, so Jesus could increase. Mary is the model of humility because she is rooted in all of her reality. And the hard reality for her is the good news for us: that Jesus came for the conversion of sinners, and not for the comfort of His mother.

Reality was that widowed and homeless, she would also become childless, first, by sharing her Son with strangers, and then by losing him to executioners. Once she had been queen for a day, when wise men came from the East. Then she became the monarch of misery as despised men tossed her the body of her Son, now deceased.

Mary is a model of humility because she is rooted in all of her reality. We think humility is concealing our blessings. The reality is Mary was blessed from crib to cross, although the former felt like gain, and the latter felt like loss. We think that humility is never drawing attention to ourselves. The reality is that at Pentecost, Mary enjoyed the greatest attention of all, the attention of the Holy Spirit, which made her sing in languages of perfect tonality, amid hearts and minds of every nationality. We think that humility is to scorn and criticize ourselves. The reality is that God has exulted Mary, not as queen for a day, but for eternity; and not just by three kings, but by all who call Christ our King.

Humility is rooted in reality. The reality is that we are all needy. We ask for Mary’s intercession because we need it. We’re poor and needy and begging for help. Mary intercedes, not based upon what we deserve, but according to our need. Humility requires that we do unto others as Mary does unto us.

So how can we priests treat each other with more humility? Not by hiding our talents, but by sharing them. Whatever talents you possess, you did not earn, and thus do not deserve. They have been given to you to share.

Humility grounds us in the reality that we are all beggars before Mary’s abundant grace, which she freely bestows on those who open their hands to the poor, before closing them in prayer to the Father. Humility alone erases our pride because humility recognizes that we are all brothers and sisters, rooted in the same earth, committed to the same grave, children of the same Father. Humility is the greatest expression of our need for Mary’s blessings that she earned and deserved, but we need and desire. Like any other beggar, we ask Mary not for what we deserve, but for what we need.

It has been said that prayer is our greatest strength and God’s greatest weakness. Well God gets weak in the knees when Mary intercedes. And Mary who debated angels, and defied kings, is wooed and won by the humility of beggars who can’t be choosers, that is, we who beg for what we need, and choose to give as we receive.

1) When have you been humiliated? Although God does not humiliate us, He can use humiliation to teach us humility. How has God done so with you?

2) Veracity, or truth-telling, is the opposite of vanity. How can you be more truthful in the way you present yourself to others? Before God? To yourself?

Patience: Luke 2:41-52

Perfectionists get a bad name. Instead of constructive criticism, perfectionists employ emotional blunt force trauma. There used to be gentle programs on television, like “Touched by an Angel.” However, the critique from the perfectionist on reality TV feels like being touched by an anvil.

So perfectionists have a bad name. However, if anyone ever had the right to be a perfectionist, wouldn’t it be the Blessed Virgin Mary? How can you not expect perfection from your son when He’s God? But this Gospel demonstrates that even Mary had to spurn perfection to learn patience.

The definition of patience is the ability to suffer for the sake of holiness. The loss of the child, Jesus, in Jerusalem caused Mary to suffer. Consider this: It is not at the foot of the Cross where the Gospels explicitly call Mary,”the Mother of Sorrows,” but rather here on the threshold of the temple. Yet, we know that Mary grew in patience, or the ability to suffer for the sake of holiness, because a spiritual sign of such patience is being compassionate. And while Scripture records not a syllable of Mary complaining, it does recall many examples of her compassion. Mary sings to Elizabeth of God, who in his compassion, raises the lowly, and feeds the hungry. Perhaps, this was a lullaby she sang to Jesus, who always associated with the lowly, and who fed the hungry. Maybe it was Mary, herself, once thought to have committed adultery against Joseph, who inspired Jesus to compassionately defend the woman, caught in the act of adultery, from the rock hurling of the stony-hearted. Mary, full of grace, is also full of compassion—a spiritual sign of patient suffering for the sake of holines

But Mary does not only grow in compassion. Mary increases in peace, which is the second sign of patience. Like many priests with their parishioners, Mary was on pilgrimage to a holy place. But her pilgrimage collapsed into crisis. She searched hysterically until she stumbled upon her child in the temple. And then she blurts the question we all ask when we endure agony we did not choose, anguish we cannot understand, and affliction we do not deserve. “Why?” Why is God allowing this happen to me?” But that is a question God rarely answers in this life because faith means we follow, not that we fathom. Who are we to fathom or understand the ways of God? Often the answer is a peaceful silence that we finally experience only after patiently following God’s will, rather than futilely attempting to fathom or understand it. Patient following of God’s will eventually restores our peace. And the restoration of peace is how the story ends. Jesus returned home just as He was supposed to, and obeyed His parents, and family life returned to normal. However, “normal” does not mean the same as it did before. Because Mary doesn’t forget: Mary ponders. She meditates on her experience of suffering.

By patiently praying over the suffering she could not avoid, or understand, Mary progressed in her relationship with God, which is the third, and surest sign of patient suffering for the sake of holiness. Previously, Mary thought she had the right to question God’s will, which is why she questioned Jesus. Maybe she thought that since she was a good person, she did not deserve to suffer evil. But as she began to patiently accept that she was a creature, and not the Creator, she started to spurn perfection in order to learn patience. Only God is perfect. Therefore, her role is not to fathom or comprehend God’s will, but to follow it. Not to understand, but to accept. Not to stretch out her hand to the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, as if she were God’s equal, but to trust God’s will, even when suffering raises questions about His will. Unlike Eve, Mary was not seduced by the need to rival God by tasting the fruit of perfect knowledge about God. Rather, Mary learned to be patient with the unfathomable unfolding of God’s incomprehensible, but always lovable, will.

So as Mary prayed, her patience grew, along with her compassion, her peace, and her relationship with God. She began to realize that though unseen, the child Jesus had never really been lost. Like God, He had always been present, even when, humanly, she could only perceive Jesus’ absence. And she finally found Him after surrendering all human effort, and simply doing what Jesus did: Follow the Father.

The virtue of patience may have been the one thing that distinguished the Hartilidge brothers, who otherwise looked very much alike. Both became priests. The older, Albert, graduated from the NAC with an STL, became the bishop’s secretary, and then vicar general of the diocese. The younger brother, George, only studied in Baltimore, and then followed the usual route from vicar to pastor. Everything always came easy to Albert. He was smart, extroverted, and self-confident. George was an introvert, who always struggled in his studies, and often with self-doubt. Albert seemed to have the perfect priesthood, which everyone thought would end in a mitre. But George’s constant struggle only resulted in mighty patience.

Then came the child abuse crisis. Albert’s classmate had to leave the priesthood, the bishop had to resign, and priests were pilloried in the press. Albert had never suffered such humiliation, and got angry when his clerical dignity was publicly questioned. George, however, had learned not to expect perfection from himself, or his parishioners, and surely not from the press. Now George suffered just as much as Albert, but his past suffering had taught him to patiently wait upon the Lord. Eventually in prayer, he felt peace when he accepted that much of what he suffered as an affront to his dignity was due to his attachment to people’s opinions. When God reminded him that he had not become a priest to be placed upon a pedestal, but to carry the Cross like Jesus, the True High Priest, George understood and accepted. Poor Albert could not. His whole world collapsed because everything his experience had prepared him for fell apart. Albert became grumpy, then angry, and finally gave up on the whole idea of priesthood.

As a seminarian, it had never occurred to George to thank God that he had had to carry a heavier cross than his brother, but it was precisely that cross which God had allowed him to suffer that gave him a back strong enough to carry his own burdens, and have patience with the struggles of others.

How do we grow in the virtue of patience? As a spiritual director for seminarians, guys often seem both surprised and pleased when I say: “You get to make mistakes, and the younger you are, the more mistakes you get to make. No wise person expects you to be perfect.” Of course, you have to admit your mistakes. You have to learn from your mistakes. You have to fess-up, and man-up, and make-up for your mistakes. That is hard. But doing the right thing, even when it is difficult, is how suffering makes us stronger, and more compassionate. I can be patient with your mistakes because I’ve committed so many of my own. Experiencing God’s love, unwearied even when our sin makes us unworthy, is how we grow in faith. And relying on God’s perfection, rather than our own, is the source of serenity.

Patience, not perfection, is a virtue. Mary is sinless, but not perfect. She dropped the occasional dish, and sometimes burned something forgotten on the oven. But unlike Eve, Mary was able to rejoice in her human imperfection, rather than try to rival God, by grasping at perfection. Mary spurned perfection when she learned patience through hard times, as when Jesus was lost in Jerusalem. Such patient pondering prepared her for the final time Jesus was lost for three days, while hidden in a tomb. That time she did not rush about hysterically like Mary Magdalene. She pondered patiently. She remembered lovingly. And she waited faithfully.

Thus spiritual writers who speak of the way of perfection don’t refer to perfectionists; they mean Mary. Mary never tried to rival God’s perfection, but suffered for the sake of sanctity, through the virtue of patience. Eve would not accept her situation, but sought to change and to perfect God’s creation. But Mary did not rush to gain the fruit of knowledge; rather, through faithful following, she patiently waited for that fruit to mature. Unlike Eve, Mary witnessed paradise unfold, as that fruit grew from the seed of the annunciation, to the fullness of the resurrection. That fruit is our salvation. And the finest fragrance of that fruit we call Mary’s Assumption.

1) What is it about the priesthood that tests your patience? How do you think God wants to use that experience for your good? How do you identify with the story of Fr. George?

2) To be perfect as God is perfect, means to be true to your nature as God is true to His nature. Does it feel natural to depend on God? When has it been difficult to do so? What was it like when you were able to really trust God, and depend upon Him?

Diligence: John 2:1-12

The highest homiletic achievement ever preached was not proclaimed by any pope. The superlative sermon in all of human history was not pronounced by any bishop. The most matchless Christian discourse ever uttered was not declared by any priest. No, this unparalleled proclamation was the declaration of the Blessed Virgin at Cana: “Do whatever He tells you.” Each word of that most sublime sermon deserves careful consideration.

“Do” is an active verb. In fact, it is an imperative or commandment. Any mother of a teenager knows this word because it is usually uttered after exhausted exasperation, as in “Just do it!” And teens know that the brevity, and volume, of this imperative means that all the excuses and rationales and complaints are over. Even Jesus accepted motherhood as a force of nature that one cannot resist. Beginning in the birth canal, when mom decides it’s time to do it, you just do it.

“Whatever” is the second word: It cuts through all the usual legalese of a contract. Because this isn’t a contract. Two people with equal legal standing enter into contracts. We’re not God’s equal, and God doesn’t enter into contracts. But God does enter into covenants. When it comes to a covenant with God, there is no way to wiggle out of “whatever.” Like God Himself, “do whatever” is all encompassing, universal, and almost unlimited. The qualification “almost” is explained by the third word in this briefest, and best of sermons.

The third word is “He,” which refers to Jesus. “Do whatever” doesn’t mean do whatever we want, or whatever we think best, or even whatever Mary prefers. Mary always defers to the Father, and refers to Jesus. In fact, in the entire Gospel of John, Mary is so deferential and referential, she is never even named. She exists only in relation to Jesus, and is referred to only as His mother. But that is like saying she was only a branch, and He, the vine. As a branch, Mary receives life from the vine, and knows that the vine is the source of every wine-bearing grape.

Therefore, when the wine ran dry, she did not have recourse to just another jar, or storehouse, all of which will eventually run dry, and none of which will ever be enough. Mary has recourse to the source, Jesus, the vine whose fruit will never run dry, and which will always give the best wine. Mary isn’t saying “do whatever the etiquette book says” or “whatever the butler suggests.” Mary is urging us to have the same trust in Christ that she had.

The fourth word in Mary’s five-star, five-word masterpiece is “says.” It is the opposite of “do.” “Says” is to talk the talk; “do” is to walk the walk. Jesus gives the marching orders, but we do the marching. However, the best way to remember this distinction is through the following dictum: Jesus never does for anyone what they can do for themselves.

Jesus will always do what only Jesus can do. Only Jesus can turn water into wine. But Jesus never does anything for anyone that they can do for themselves. So Jesus doesn’t fill the jars with water. Jesus doesn’t draw out a sample, nor gives it to the headwaiter. Jesus doesn’t taste the wine, nor call over and comment to the bridegroom. Jesus will always do what only Jesus can do. But Jesus never does anything for anyone that they can do for themselves.

I am referring to the virtue of diligence, or the ability to do, to act, and to persevere, despite difficulties in doing whatever Jesus says. We call Mary “Help of Christians” because she helps us to be diligent. As St. Ignatius Loyola explains, she teaches us to work as if everything depends on us, but to pray because everything depends on God. We walk His talk, believing that Jesus will always do anything that only He can do, while insisting that we do everything we can do. Diligent people, like Our Lady Help of Christians, understand what an old peasant in Honduras once told me: “God makes the corn grow. But he doesn’t make the tortillas for you.”

Diligence is what helped Father Foster when he had been in his new parish less than a month, and his DRE was arrested for sexual misconduct. Fr. Foster had not hired the layman, had not supervised him, and had no taint of blame for what happened. He wanted to blame the former pastor, move to a new parish, anything except pick up the pieces of a parish he had not broken. But his past diligence, and present prayer, helped him decide:

This is not my fault, but it is my problem. God never promised I wouldn’t suffer, but He did promise I wouldn’t be overwhelmed. I’ll accept this Cross I didn’t request, and don’t deserve, for love of Christ, Who for my sins, accepted the Cross He did not deserve.

But diligence is not something priests leave up to job-training. If we practice diligence now, the virtue will sustain us later. When life throws us a curve, diligence reminds us it’s just a learning curve. With God’s help, we can overcome. Thus, diligence is learning from a poor sermon. Instead of collapsing into self-pity, we poll our parishioners, speak to our colleagues, or ask experts how we can improve. Diligence is accepting criticism, and instead of complaining or gossiping, we pray and strain to listen and learn from critiques. Diligence is the determination that because all things work for the good of those who love God, we will bear hardship and disappointment through tenacity to final serenity.

Diligence is the faith that Jesus will always do what only Jesus can do, but also the confidence that Jesus never does for us what we can do for ourselves. Compared to what Jesus does, our works are tiny. But when based on whatever Jesus tells us to do, our tiny bit of diligence is the active cooperation in faith we need to believe.

Marvel at the diligence of His mother. In just five words Mary helped Jesus believe that His hour had come. She could talk the talk because she had already walked the talk. Mary had diligently done whatever God told her. God spoke, and Mary gave birth. God spoke, and Mary fled to Egypt. Based on whatever God told her to do, her tiny bit of diligence was the active cooperation in faith Jesus may have needed to believe that His hour had come.

Mary is telling us all that our hour has come. That is why the last word of her sermon is “you.” Because the greatest miracle Mary could work today is to help a priest make real her appeal: Do whatever Jesus tells you. When we’re concerned about getting discernment right, it’s important not to get diligence wrong. Because if every day we do whatever Jesus tells us, we’ll find that like wine, He saved the best for last by making the big decisions easy, because we diligently responded to all the daily difficult ones.

1) Can you find a single instance where Jesus does what someone else could have done just as well? On the other hand, can you find a single instance where Jesus does not do what only He can do? What does this tell you about your faith in Christ, and your confidence in yourself?

2) Everyone struggles. Some struggle with their weight, or social awkwardness, or bear scars of past trauma. What has been your greatest difficulty? How has God helped you to persevere?

Continued in Part 2, here.

Recent Comments