In a 2016 interview that was arranged by Fr. Antonio Spadaro, S.J., the editor of La Civiltà Cattolica, prior to the trip to Sweden for an ecumenical gathering anticipating the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, Pope Francis expressed something that he has voiced several times during his pontificate: “to proselytize in the ecclesial field is a sin.” He added: “Proselytism is a sinful attitude.” In a recent address to the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, he repeats this point, saying that “proselytism is poisonous to the path of ecumenism.” And even more recently, in his prepared address for his visit to Roma Tre University, he repeated this point, although more generally, namely, that in witnessing to the Christian faith, he did “not wish to engage in proselytism.”

This is strong language, and deserves careful attention, because many think the pope is saying the Catholic Church should no longer evangelize other Christians. That’s a large question that would take extensive treatment. Here, I’m going to limit myself to the “ecclesial field,” in the pope’s phrase, of ecumenical dialogue. Unfortunately, Francis did not define what he means by proselytizing, and did not distinguish it from evangelizing. But since his 2013 Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii gaudium, he clearly desires the Church to be called to evangelize, given her missionary nature. So, there is a difference here to be drawn. Francis, however, simply states that proselytism as such is a sin or is poisonous. But he doesn’t tell us why. Nor does he distinguish between unethical and ethical means of proselytizing. It helps to turn to a document produced by a working group organized by the Catholic Church and the World Council of Churches: “The Challenge of Proselytism, and the Calling to Common Witness.” The group formulated some basic points about what would constitute improper “proselytizing” in an ecumenical context:

1. Unfair criticism or caricaturing of the doctrines, beliefs, and practices of another church without attempting to understand or enter into dialogue on those issues.

2. Presenting one’s church or confession as “the true church” and its teachings as “the right faith” and the only way to salvation.

3. Portraying one’s own church as having high moral and spiritual status over against the perceived weaknesses and problems of other churches.

4. Offering humanitarian aid or educational opportunities as an inducement to join another church.

5. Using political, economic, cultural, and ethnic pressure or historical arguments to win others to one’s own church.

6. Taking advantage of lack of education or Christian instruction, which makes people vulnerable to changing their church allegiance.

7. Using physical violence or moral and psychological pressure to induce people to change their church affiliation.

8. Exploiting people’s loneliness, illness, distress or even disillusionment with their own church in order to “convert” them.

Pared down for present purposes, only the second point raises fundamental ecclesiological questions (the rest may be accepted as unethical means, without any real theological difficulty). The ecclesiological question has to do with ecclesial unity and diversity in the one and only Church of Jesus Christ, the Catholic Church.

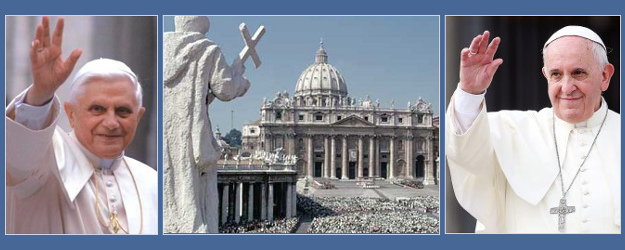

In his address to the Pontifical Council, Pope Francis reiterated the teaching of Vatican II, and that of his two illustrious predecessors, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, namely: “Dialogue is not simply an exchange of ideas. In some way it is always an ‘exchange of gifts’. . . . a dialogue of love” (Ut Unum Sint, §§28, 47). Furthermore, he also repeats the statement of Pope Benedict XVI who, at an ecumenical meeting during his 2005 Apostolic Journey to Cologne on the occasion of the 20th World Youth Day, said, “…unity does not mean what could be called an ecumenism of return: that is, to deny and to reject one’s own faith history. Absolutely not! It does not mean uniformity in all expressions of theology and spirituality, in liturgical forms and in discipline” (“God’s Revolution,” World Youth Day and Other Cologne Talks, 85).

How should we understand the rejection of what is called here an “ecumenism of return”? Is Benedict XVI suggesting that the Catholic Church should no longer understand herself as the one true Church? Is he implying that there are many ecclesial expressions of the one Church that Christ founded, all being part of the one Church, and hence that the Church of Jesus Christ also subsists in these others churches and ecclesial communities? In other words, is Benedict XVI affirming ecclesiological relativism or pluralism?

The answer to this question is “no.” In the Catholic Church alone is given the fullness of all means of salvation. The Church of Jesus Christ does not subsist in other churches and ecclesial communities, but only subsists in an undetachable and lasting way in the Catholic Church. Therefore, the essential unity of the Church is already present in it. But unity is a gift and a task; the latter precisely because of the division among Christians. Furthermore, as Vatican II’s Lumen gentium §8 affirms, there are elements of truth and sanctification existing outside the visible boundaries of the Church, and these do not exist in an ecclesial vacuum, but rather in ecclesial communities: the written Word of God, the life of grace, faith, hope, and love, and other gifts of the Holy Spirit, and visible elements of sanctification and truth, such as the sacrament of baptism. To the extent that these elements are present, the Church of Jesus Christ is efficaciously present in these— particular churches to a lesser or greater degree. But the presence of these elements of sanctification and truth also means, as G.C. Berkouwer (1903-1996), the Dutch Reformed master of dogmatics and ecumenical theology, correctly states when describing the teaching of Vatican II—“‘Fullness’ is not always contrasted to ‘emptiness’, but also to incompleteness and partiality.” Catholicity, then, like unity, stands in the light of gift and task.

Still, note well that Benedict XVI distinguishes in his ecumenical speech between “unity” and “uniformity.” In making this distinction, Benedict is following Vatican II by not requiring “uniformity” in four distinct and specific areas of the Church’s life: theology, spirituality, liturgical forms, and discipline. He is referring here to Unitatis Redintegratio:

All in the Church must preserve unity in essentials. But let all, according to the gifts they have received, enjoy a proper freedom in their various forms of spiritual life and discipline, in their different liturgical rites, and even in their theological elaborations of revealed truth. In all things, let charity prevail. If they are true to this course of action, they will be giving ever better expression to the authentic catholicity and apostolicity of the Church (§4; emphasis added).

It is significant that Vatican II refers, in particular, to “the differences in theological expression of doctrine” (emphasis added). In other words, different theological traditions “have developed differently their understanding and confession of God’s truth. It is hardly surprising, then, if from time to time, one tradition has come nearer to a full appreciation of some aspects of a mystery of revelation than the other, or has expressed it to better advantage. In such cases, these various theological expressions are to be considered often as mutually complementary rather than conflicting” (§17; emphasis added). I think this claim about the legitimacy of diverse theological expression and articulation is at the root of the rejection of the notion of an ecumenism of return.

Thus, in rejecting this notion of ecumenism, Benedict is not implying that there are many churches and hence, urging the acceptance of ecclesiological pluralism or relativism, that is, with the Catholic Church being merely one among many churches. Rather, he means that we can no longer speak of a simple “return” to the Church as an ecumenical demand for non-Catholics when that is taken to mean, as the French Catholic ecclesiologist, Yves Congar, rightly states, “absorption or annexation by the Catholic Church, as if they themselves had no contribution to make to us as full and as ‘catholic’ a realization as possible of Christianity.” In other words, our separated brethren have a real contribution to make to the fuller realization of the Church’s unity and catholicity, and hence, to the fullness of understanding and living of Catholic truth.

As Vatican II stated, they may come nearer to a fuller theological appreciation and expressions of some aspects of revealed truths, and “these various theological expressions are to be considered often as mutually complementary rather than conflicting.” To use the term coined by the American Catholic dogmatic theologian, Thomas Guarino, this position may best be called “commensurable pluralism.” In the words of the Decree on Ecumenism: “In dialogue, one inevitably comes up against the problem of the different formulations whereby doctrine is expressed in the various Churches and Ecclesial Communities. This has more than one consequence for the work of ecumenism. In the first place, with regard to doctrinal formulations which differ from those normally in use in the community to which one belongs, it is certainly right to determine whether the words involved say the same thing. . . . In this regard, ecumenical dialogue, which prompts the parties involved to question each other, to understand each other, and to explain their positions to each other, makes surprising discoveries possible. Intolerant polemics and controversies have made incompatible assertions out of what was really the result of two different ways of looking at the same reality. Nowadays, we need to find the formula which, by capturing the reality in its entirety, will enable us to move beyond partial readings, and eliminate false interpretations.”

Furthermore, adds Congar, “A Catholic ecumenism cannot forget that the church of Christ, and of the apostles, exists. Therefore, the point of departure for Catholic ecumenism is this [already] existing church, and its goal is to strengthen, within the church, the sources of catholicity that it seeks to integrate and to respect all their legitimate differences.” In short, the unity of the Church is a complex notion; it is both gift and task, both indicative and imperative. Disunity is, thus, ultimately a failure to recognize the full measure of the one body of Christ, of that “of the Catholic Church,” and, as Congar adds, “in this sense it would not be another church, that is, an ecclesial body other than the Catholic Church, the Church of Christ and of the apostles.”

Therefore, in an ecumenical dialogue, we must avoid the following either/or dilemma in answering this question about the diversity of churches in the one and only Church, the Catholic Church:

Either correctly affirming that the Church of Christ fully and totally subsists alone in its own right in the Catholic Church, because the entire fullness of the means of salvation are present in her, and then implausibly denying that Orthodoxy and the historic churches of the Reformation are churches in any real sense, such that there exists an ecclesial wasteland outside the Church’s visible boundaries (Lumen gentium §8; Unitatis redintegratio §§3-4; Ut Unum Sint, §14);

Or rightly affirming that they are churches in some sense, in a lesser or greater degree to the extent that there exists ecclesial elements of truth and sanctification in them, but then wrongly accepting ecclesiological relativism or pluralism—meaning, thereby, that the one Church of Christ Jesus subsists in many churches, with the Catholic Church being merely one among many churches (Lumen gentium §8; Unitatis redintegratio §§3-4, 20-21, 23).

Thus, adds Ratzinger, “the true Church is a concrete reality, an existing reality, even now.” Put differently, it is about catholicity in a concrete form. The Church is a concretum universale. Walter Cardinal Kasper explains:

Just as in Jesus Christ, God has taken form not in any general humanity, but by becoming “this” man Jesus of Nazareth, it is analogously true that the fullness of salvation revealed in Jesus Christ is also present in the Church in a concrete, visible form. Thus, the Catholic Church is convinced that in it—which means in the church in communion with the successor of Peter and the bishops who are in communion with him—the Church of Jesus Christ is historically realized in a concrete, visible form, so that the Church of Jesus Christ subsists in it—in other words, it has its concrete form of existence.

This constitutive feature of Catholic ecclesial identity, as correctly underscored by Kasper, does not imply that others outside the Church are not Christians or, adds Ratzinger, “dispute the fact that their communities have an ecclesial character.” They don’t exist in an ecclesial vacuum. True, they exist in real communion with the Church, the Catholic Church, but they are “true particular churches” (Dominus Iesus §17) only in some analogous sense since they remain in “imperfect communion” with that Church (Unitatis redintegratio §3). The Council describes these “true particular churches” as “positive ecclesial entities” (as Ratzinger phrases it), and, in addition, says Ratzinger, since “uniformity and unity are not identical,” this means that “a real multiplicity of Churches must be made alive again within the framework of Catholic unity.”

Summarily stated, the then Cardinal Ratzinger put the question regarding the unity and pluriformity of the one Church this way:

[The] Catholic tradition, as Vatican II newly formulated it, is not determined by the notion that all existing “churchdoms” are only fragments of a true church that exists nowhere, and that one would have to try to create by assembling these pieces: such an idea would render the Church purely into a work of man. Also, the Second Vatican Council specifically states that the only Church of Christ “subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him” [Lumen Gentium 8]. As we know, this “subsists” replaces the earlier “is” (the only Church “is” the Catholic Church) because there are also many true Christians, and much that is truly Christian outside the [visible boundaries of the] Church. However, the latter insight and recognition, which lies at the very foundation of Catholic ecumenism, does not mean that, from now on, a Catholic would have to view the “true Church” only as a utopian idea that may ensue in the end of days: the true Church is in reality, an existing reality, even now, without having to deny that others are Christian, or to dispute the fact that their communities have an ecclesial character. . . . However, that unity of the one Church that already exists indestructibly is a guarantee for us that this greater unity will happen someday. (“Luther and the Unity of the Churches,” (1983), Church, Ecumenism, & Politics, 118-20)

Clearly, the Church regards non-Catholic Christians, by virtue of our one common baptism, as belonging, however imperfectly, to the household of faith, i.e., the Catholic Church, and hence she speaks of them as “separated brethren,” brothers and sisters in the Lord Jesus Christ. Indeed, the Church expresses its identity as the one Church of Jesus Christ by establishing a relationship of dialogue with these churches. Dialogue means we all learn from each other and don’t dismiss each other out of hand. We must still speak the truth, in love (Ephesians 4:15), however, in our search to realize a fuller unity, namely, the fullest communion that includes unity in the faith, in the sacraments, and in church ministry (Lumen Gentium, §14; Unitatis Redintegratio, §2). Full visible communion is the goal of ecumenical dialogue.

The Second Vatican Council made a courageous step forward toward the unity of all Christians, according to the then Joseph Ratzinger. Indeed, the movement towards ecumenism, Ratzinger explains, “is the genuinely ecclesiological breakthrough of the Council,” and, significantly, is an important illustration of the hermeneutics of continuity and renewal, and hence that development is organic and homogeneous. In other words, the Council found a way within “the logic of Catholicism for the ecclesial character of non-Catholic communities . . . without detriment to Catholic identity.” Constitutive of Catholic ecclesial identity is that the Church of Jesus Christ is a single reality.

Ratzinger adds, “this one and only Church, which is at once spiritual and earthly, is so concrete that she can be called by name.” That is, she is “constituted and organized in this world as a society,” and “subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter, and the bishops, in union with that successor.” “This declaration of the Second Vatican Council,” states Mysterium Ecclesiae §1—a 1973 intervention of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith—“is illustrated by the same Council’s statement that ‘it is through Christ’s Catholic Church alone, which is the general means of salvation, that the fullness of the means of salvation can be obtained’ [Unitatis Redintegratio, §3], and that same Catholic Church ‘has been endowed with all divinely revealed truth and with all the means of grace’ [§4], with which Christ wished to enhance His messianic community.”

And yet, the Church must heed Jesus Christ’s call to unity. As John Paul II put it: “How is it possible to remain divided, if we have been ‘buried’ through Baptism in the Lord’s death, in the very act by which God, through the death of his Son, has broken down the walls of division?” “With non-Catholic Christians,” the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith states, “Catholics must enter into a respectful dialogue of charity and truth, a dialogue which is not only an exchange of ideas, but also of gifts, [indeed, a dialogue of love], in order that the fullness of the means of salvation can be offered to one’s partners in dialogue. In this way, they are led to an ever deeper conversion in Christ” (Ut Unum Sint, §§28, 47; Lumen Gentium, §14; Unitatis Redintegratio, §2). This is receptive ecumenism at its best. It is the fruit of an ecumenism of encounter and spiritual friendship. In conclusion, there are three dimensions in ecumenical dialogue, namely, and “above all,” there is: [1] listening, as a fundamental condition for any dialogue, then, [2] theological discussion, in which, by seeking to understand the beliefs, traditions, and convictions of others, agreement can be found, at times hidden under disagreement. This second dimension includes ecumenical apologetics. Such apologetics and receptive ecumenism are not at odds. It is best illustrated in a book such as Matthew Levering’s Mary’s Bodily Assumption.

Accordingly, we may conclude with Berkouwer, who shares the heart of the ecumenical calling: “The very mystery of the Church invites, rather compels us, to ask about the perspective ahead for the difficult way of estrangement and rapprochement, of dialogue, contact, controversy, and for the ecumenical striving to overcome the divisions of the Church.” Furthermore, he adds, “Our thoughts about the future of the church must come out of tensions in the present, tensions that must creatively produce watchfulness, prayer, faith, and commitment, love for truth and unity, love for unity and truth.” Love for the truth is the dynamic behind any authentic quest for unity between Christians, and the love for unity— “our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ” (1 Jn 1:3)—for acceptance, reconciliation, and communion, is a desire for unity in the truth of faith and doctrine. Clearly, Berkouwer does not play truth and unity against one another, and, for that matter, neither does the Catholic Church.

Moreover, “Inseparably united with this is another essential dimension of the ecumenical commitment: [3] witness and proclamation of elements which are not particular traditions or theological subtleties, but which belong rather to the Tradition of the faith itself.” This third dimension flows from the Catholic conviction that the entire fullness of the means of salvation is present in the Catholic Church. “In this connection,” the Congregation adds, “it needs also to be recalled that if a non-Catholic Christian, for reasons of conscience and having been convinced of Catholic truth, asks to enter into the full communion of the Catholic Church, this is to be respected as the work of the Holy Spirit, and as an expression of freedom of conscience and of religion. In such a case, it would not be a question of proselytism in the negative sense that has been attributed to this term.” This is the essential difference between negative and positive proselytism, the latter—as the Church clearly teaches—being an integral aspect of evangelization, even in the “ecclesial field.”

It’s interesting that the notes on comments state, ‘…those that are deemed by the editors to be needlessly combative and inflammatory…’, will not be published, because, in my experience there are two predominant types of Evangelist – effective and ineffective – and almost all the Catholic ‘evangelists’ I know are ineffective because they are: ‘needlessly combative and inflammatory’. :)

That is, they might well be a, ‘walking, talking, vade mecum of the Catechism and Canon Law’, so have a head full of correct ‘facts’, but they seem also completely lacking in wisdom (phronesis) and any ability to ‘read people’ (i.e., they seem to be what is commonly referred to as ‘anally retentive’), and so frequently just parrot or posit statements/answers in a wooden way.

Sadly, it’s as if by nature, predominantly intellectual types (esp. school teachers) who like logic-chopping and debating are drawn to catechesis and anything in this realm, too. Should we be cautious about this? It’s fine in the classroom (where it’s meant/expected to be?), but what about letting that mindset loose in the everyday life of an ordinary congregation, or even those outside Protestant academia?

Often, for example, their character’s seem to lack, well, character, and they just come across as frustrated, angry, or bitter (that people aren’t doing/believing what they want them to). Even the simplest people have a natural ability to ‘smell something fishy’ about people – that they’re being used or manipulated in some game, even if the interaction isn’t obviously stilted or disingenuous (which often it is). :(

Most lapsed, or on the fringes, let alone the people in our congregations, for example, aren’t postgrads in theology, yet when watching zealous types going at it, you’d think the people they were talking to must have a degree in theology, or else wonder what the evangelist must have been smoking the night before… :)

Surely, in most cases, what is required is far more than merely intellectual knowledge and skill. But, I’m not suggesting they need to be ‘pastoral’ – i.e., dumb it down – (Lord save us from ‘pastoral’ types!) but that Evangelisation is an *art*, not an algorithmic procedure where, if you line up all the ducks, they’ll just fall into the bag, as if however poor someone’s social skills are, they are irrelevant.

One of the biggest mistakes I see, seems to be an inability to tell ignorance from Modernism. So often, it seems to me, their ‘victim’ might be spouting Modernism, but that doesn’t make them a Modernist. In most cases, it makes them the product of all (the error, misrepresentation, and lies) they’ve been taught and picked up, ‘by osmosis’ – and sadly in many cases ‘catechesis’ – but not deliberately. So, by all means, take on those catechists! But again, wisely, in the manner of genuinely wanting to help them ‘see the light’, rather than simply correct them which almost inevitably ends in an unresolveable clash.

For example, if the testimony (‘narrative’) of people they trust tells them (our beloved) Papa Benedict is a rottweiler and they have to be careful, if people they don’t trust then push him in their face, they will get defensive: and understandably so. It’s not that they’re heretics. It’s that they’ve been conditioned to be scared (but that doesn’t mean that fear is based on a sound foundation).

What’s more, pressing the point – as most of these ‘evangelists’ do when they sense resistance – just makes them feel more cornered, and likely to respond even more negatively. If anything, then, it reinforces the ‘cycle of danger’ voiced in the narrative they have been fed: ‘Ratzinger’ and his followers are vicious and nasty.

That is, on both sides, self-fulfilling narratives are reinforced. People who take ‘Ratzinger’ seriously ARE nasty, and people who don’t, ARE Modernists.

Now, of course, we can’t discount grace (which builds on nature), but with those people it seems a miracle would be required! In fact, in many cases, the more people tell them to ‘get lost’, the more it confirms them in their approach (which obviously need sharpening, to their mind). I saw it constantly in Evangelicalism with the same ‘evangelist’ character types, and their reading of verses like, Matthew 10.22 & 24.9, Mark, 13.13, John 15.18, as confirmation of their approach as being correct. Now, I hear the same mindset from zealous ‘New Evangelists’ (sadly, many of them young). The irony is, of course, these ‘Orthodox Catholics’ are are exemplifying the worst traits of ‘Evangelism’: which didn’t even work for Protestantism!

That is, skilled evangelists rarely get into a fight, and have a productive thought-provoking conversation (which opens the door for further conversation), whilst most of the Catholic ‘evangelists’ I’ve watched in action precipitate a train-wreck after a few minutes through being deliberately provocative and belligerent rather than wise and intelligent. The first group ‘leave a stone in the shoe’ – a question in the mind – of their interlocutors, to think about Catholicism afresh, rather than try to get them to confess Catholicism as the One True Faith, by the end of the conversation. That is, they behave just like the old ‘street evangelist’: on their favourite sola, ‘transmit alone’.

That is, ‘artful’ evangelists are patient, if needs be, and know when to apply the brakes in order to continue the conversation later, rather than alienate by insisting on a ‘scalp’ or ‘close the deal’. They don’t have the door close permanently, because their evangelisation is not ‘all about me’: about the evangelist feeling good about themselves ‘getting a sale’, but respecting the person they are evangelising, and relying on the combination of Holy Spirit, faith, patience, reason, grace, etc..

Sadly, most of the self-styled ‘evangelists’ I’ve known – Protestant or Catholic – are untrained, but also obsessed with winning arguments. And, as often is the case in parishes, the most unsuitable people volunteer for the very things they’re least skilled at. In this case, they are people who get fun out of the combat. They like like to smell the blood in the water. They see themselves as ‘Gladiators for Jesus’. That is, the only aspect (out of the three) the New Evangelists I know have, is Ardour. They are completely clueless about Method or Expression.

It is those very people who are clueless in these two areas who end up angrier and angrier and increasingly pedantic because their failure rate is so high and experience so much rejection and rebuff. They conclude the problem is they must lack facts or skill in debating – if only they knew more or how to argue better, they’d succeed – when the problem is their *only* skill is in debating: the buzz they get from trying to slice people up, and then expecting them to be grateful for it. That is, they ‘sharpen up’ on exactly the wrong thing.

We need Evangelists rather than butchers. Being able to ‘slice and dice people’ (as it is people, not merely a piece of meat – an argument – they’re dealing with) – objectifying, rather than seeing a subject – seems doomed to failure.

Oops!: ‘That is, they behave just like the old “street evangelist”: on their favourite sola, “transmit alone” ‘ = ‘bad’ evangelist.

Evangelist v. apologist v. catechist. There’s a time and place for each. Knowing the right place and time is key is key. Also, knowing your audience devout or practicing Catholic, non-practicing or estranged Catholic, non-Catholic Christian (what type?), non-Christian (again, what type?), personality, cultural and social factors. In any event, always with humility and charity. Peace.

In my opinion, if it is no longer permissible to ask a non-Catholic Christian to consider coming into the Catholic Church then the Church has hopelessly lost its way.

Interesting idea, but that’s where I part company with Echeverria, and all those “dissenters” obsessed with “Amoris Laetitia”, too. Reminds me of Evangelicalism where the pedantic obsessed over the meaning of single bible verses, out of the context of the whole, so it lost any meaning anyway.

I’m not a theologian, but to think the church or the magisterium has somehow gone off the rails, or is likely to go to the dogs over a footnote, “works” in Protestantism, as it does not have any substantial ecclesiology, just bible verses. But to imply Christ can be derailed from his mission by the equivalent of a decontextualised bible verse, a pope they consider a rogue, or that Christ could lose his way (as the church is not merely a fallible, human organization, I find hard to take.

“But to imply Christ can be derailed from his mission by the equivalent of a decontextualised bible verse, a pope they consider a rogue, or that Christ could lose his way (as the church is not merely a fallible, human organization, I find hard to take.”

Okay. But since folks such as Dr. Echeverria aren’t making that argument, what’s your point? And what of the fact—not opinion, but fact—that various national bishops’ conferences are taking a footnote (it’s much more than that, of course) and saying that, yes, in some cases the perennial teaching of the Church about Holy Communion for the divorced-and-civilly-remarried no longer applies? And if you are going to lambast the “dissenters” over specific words and fine print, then maybe you also have a problem with, say, the fathers at the Council of Nicaea?

Hi there, Dr Olson. Sorry, it was a clumsy attempt to defend the Church against the charge, by ‘Don’, that, ‘In my opinion, if it is no longer permissible to ask a non-Catholic Christian to consider coming into the Catholic Church then the Church has hopelessly lost its way.’

You, of course, know better than I, as I have read your books, learnt from them, and respect you as a teacher, but my issue is more about method, than content (although I know content is important):

How much can we persuade people who are determined to read their own viewpoint into something for their own ends? Might direct confrontation simply entrench a person in their position – not wanting to lose face – and so even more determined to justify their own viewpoint, so we become the grindstone for them to sharpen their case, and strengthen their resolve to get others to believe their viewpoint against us? Do we, as it were, through our approach, encourage them to become bloody-minded and determined, more than in a manner which gives them pause to reflect on their position?

To me, there seem to be different ways of challenging. Some which engender reflection, and others, merely a counterblast, and there are skills associated with the former, and are quite successful at allowing people to change their mind without losing face or it ending in a battle.

There is a school of Reformed Evangelists teaching it, and it very much overlaps with what’s termed ‘Street Epistemology’ which some atheists use to ‘deconvert’ people, with as little fighting as possible.

I’ve seen it work in concrete situations where normally there would be a clash, but there is a respectable discussion instead…

Of course, that doesn’t gainsay the sadness over the bishops, but as the method I’ve mentioned above says, ‘Don’t argue with the man with the mic’. In other words, what is gained taking on a superior force with a frontal assault? Might some other strategy and tactics be more effective?

PS Thank you for all you do at Ignatius Press. It’s a publisher I can trust.

The intended implication of my post was that of course it has not (and never will be) formally declared impermissible to ask a non-Catholic Christian to consider coming into the Catholic Church. So, the Church has not lost its way despite some people wanting to discourage the seeking of conversions.

Everyone should read Pope Emeritus Benedict’s recent comments about the “deep double crisis” that has developed in the Church since Vatican II relating to a) its loss of missionary spirit – ie, loss of the desire, will and effort to seek converts; and b) the collapse of practice of the faith among baptized Catholics.

His basic point seems to have been that for many modern Catholics the idea of seeking conversions to the Catholic faith has become an absurdity since they have concluded most people can be saved without need of formally entering the Church. Likewise, many Catholics (perhaps subconsciously) ask themselves “If others can be saved without following the precepts or disciplines of the Church, then how can it be true that I might be lost for not following them?”

See here: https://www.christiantoday.com/article/church.in.deep.crisis.as.catholics.abandon.traditional.doctrine.says.former.pope.benedict.xvi/82078.htm

Pope Francis wants to recover the Church’s missionary spirit. See, Evangelii Gaudium. The question is, does he have the right strategy? He seems opposed to actively seeking conversions. Rather, he seems to believe the best way is by living as credible witnesses to the Gospel. He says “The Church grows by attraction.” He also seems to be okay with a Catholic witnessing to (that is, explaining) what it is that brings him such joy and peace – if he is asked. All of which is very good and true. But on the other hand, he seem stridently opposed to actively seeking the conversion of others to the Catholic faith – probably because he thinks it is often done poorly and is therefore counterproductive. However, he has also actually suggested that Catholics should discourage those who express a desire to convert, and has stated that he personally is not seeking to convert Evangelicals to the Catholic faith, but rather, that they should seek God within their own communities. We’re also all aware of specific instances where, as Archbishop, discouraged those who expressed a desire to convert.

Maybe Pope Francis, being from South America, where evangelicals, Mormons, and Jehovah’s witness use unethical methods to attract Catholics to their communities, even offering them money, which, of course, they will pay back once they begin to tithe in that sect. Yes. the fact is that many, especially the poor and those with only a very basic education are not well catechized in the Church, so they are prey to such tactics by these Evangelicals, Pentecostals, and other such sects. Maybe he thinks that some Catholics are prone to this kind of activity, but that is not the case. In fact, in a survey of all religions and denominations, it turns out that Catholics are the worst evangelizers. He seems to have a “thing” about this which is excessive, perhaps due to this background. I have lived in Argentina, Chile and Peru.

There is good proselytizing and bad proselytizing. There is good evangelizing and bad evangelizing. The words themselves are not the problem.

Whatever happed to ” You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free”? If no one speaks the truth to people, how will they seek to know it?

I’ve just been watching ‘The Journey Home’, the programme where Marcus Grodi interviews people who have come into the Catholic Church. It put all this talk above into its true perspective. While some talk about what we can/cannot do or should/should not do, other people in the Church are just getting on with it. And doing a great job, I would say.