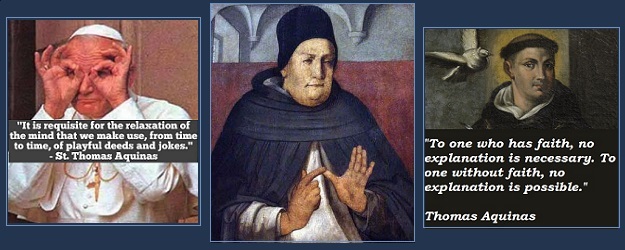

Saint Thomas Aquinas by Pedro Berruguete (c. 1450 – 1504)

(And, yes, the photo on the left is actually St. John Paul II early in his pontificate!)

Everyone needs to develop a certain flexibility in life or one simply becomes a grump, unable to be a healthy and realistic optimist in the face of trials and difficulties, failures and other mishaps of life. The flexible person first knows how to laugh at self because we humans are fickle or changeable, and so filled with many imperfections. For example, some if not most, often make many promises and resolutions, and do not always keep them (think of new year’s resolutions and Lenten practices). We make modest efforts for improving ourselves in terms of virtue, but these attempts sputter and, often, we do not persevere for many reasons, both true and false. Taking care of three screaming, mischievous, and energetic children, both mothers and fathers try to reason with them to no avail. Parents, in turn, become screamers themselves, hoping to create an immediate character of obedience in their kids, which only makes things worse. So, enter humor and laughter.

If part of humility means accepting one’s limitations, then that means a willed death to an obsessive perfectionism in one’s self, as well as a domineering attitude to one’s children, spouse, employees, or co-workers. The virtue of humility does not expect life to be perfectly balanced by what are reasonable expectations. The humble mind not only knows truth, but relishes it, and does not become bored with it. As this becomes second-nature, so humor and laughter temper one’s life, whether it be with one’s mistakes, imperfections, and even sins of weakness found in oneself or others. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that if I laugh a great deal, I am necessarily humble, because jokes can be cruel and mean, dirty and obscene. Humor can sometimes stymy or mask the inability to face reality’s hard questions in marriage, or family life, or the workplace. The best humor seems to be innocent, as we tend to love the clown, or the mime, as well the child’s sometime absurd answers to questions.

I am thinking of several cartoons in the New Yorker magazine that bring at least a smile to some, or at least to me:

A prisoner arrives in his jail cell. Looking at a dead man in a chair, he asking the dead man: “How’s the eggplant Parmesan in this place?”

One housewife says to another: “It is so nice being on vacation, and having different things to complain about.”

At a meeting of a financial company, the CEO says “As board members, we need to speak with one voice. I’m suggesting Donald Duck.”

They each have their own strange logic of the unexpected.

Laughter among adults flows from seeing the unexpected and real paradoxes in life which can get very ridiculous. Reason and experience expect one outcome, but people normally become greatly surprised by the very unexpected consequences. Understanding the unexpected in life’s ordinary incidents leads to delight in jokes—a kind of refreshment, similar to an aesthetic experience. However, suddenly losing a lot of money or property, of course, is not funny. It can be the joy of envy if someone we dislike, or feel envious toward, loses “good fortune.”

Often having a baby leads to lots of smiles and laughter, playing peekaboo games. Tickling and rough-housing one’s small child becomes delightful to parents and youngsters alike. A good sense of benign humor comes in handy when children misbehave, lest parents go overboard in demanding absolute perfection, only to be disappointed.

St. Thomas has his usual comments to say about simple things like humor. He writes about it (ST II-II 168, 4) and asks the question whether there is a sin in its lack thereof. He agrees with Aristotle that there can be a sin in this area of life when it flies in the face of right reason, and becomes disproportionate in the circumstances. Further he develops his ideas relying on Seneca, who says that a lack of wisdom among one’s associates and neighbors leads people to think you have become rude or a cad, that is, disregarding others’ feelings. Then he explains further what he means by saying: “Now a man who is without mirth, not only is lacking in playful speech, but is also burdensome to others, since he is deaf to the moderate mirth of others.” He slips in Aristotle by further concluding that people like this are sometimes “vicious…boorish or rude.”

Aquinas explained earlier (ibid. 2) that mirth is helpful to one’s life of virtue because it gives rest and pleasure; whereas virtue without it leads to weariness, either of the body or the soul. From this, one can conclude that without timely rest or pleasure, the tensions of work, or even contemplation, would lead to a breakdown (perhaps just giving up the virtuous life) if the tension is never relaxed. In other words, humorous jokes, and turns of phrase rightly enjoyed moderately, enables one to return back to the seriousness of work—either in the intellectual realm, or boring work, and often harsh labor—with a renewed strength of determination for the sake of one’s family, as experience manifestly shows. A person with a “happy return of mind” creates the atmosphere of fulfilling his responsibilities with cheerfulness, as Aquinas continues to say.

Certainly, developing a sense of humor is not the highest of virtues—as are the theological ones, or matters of strict justice and chastity—but this small virtue of mirth supplements or aids them when circumstances demand this virtue. Without it, one becomes trapped in brooding, or negative feelings, stirred up out of dark thoughts. To keep one from becoming overly pessimistic—about the problems of the cultural or parish wars concerning liturgy or parochial policies—is a great help to a spirituality of hope. Therefore, being able to laugh moderately by seeing the silly side of the non-serious is necessary for not only pro-life workers, but even salvation itself. It keeps us from being enslaved by a gloomy spirit, leading us to lose trust and confidence in God.

Two very fine authors, which I quoted in a small work I once wrote, make the following claims:

“Because laughter assumes an agreement about core values, joke-telling also signals common sympathies… People who regard radical feminists or political correctness as ridiculous are apt to share many other beliefs as well. They are less ready to quarrel, and more likely to form bonds of attachment. By contrast, an inability to laugh together signals either a profound disagreement about basic values, or a mutual antipathy.”1

“(Humor) also has a social function by satire, achieve acceptance by others, creates group unity, strengthens friendships. Sometimes it releases fears, anxieties, even self-disparagement, or relaxing from excessive ratiocination.”2

“Telling jokes makes others like us. So, it can begin an acceptance of the group which lessens tensions and conflicts. Cohesion means the members are attached to one another.3

Buckley further mentions the potential for creating a social relationship that humor has: “…Laughter erases distances between people… we cannot imagine true companionship without laughter…” Sometimes, we can disarm people’s prejudices against us. They often do not listen to those of us bringing the culture of life because we sometimes appear to be from the kingdom of grim! It is easy to notice this situation in the Church with the controversy of the Cardinals posing five questions to the Pope. While it is a very serious issue, those who think the Cardinals are either heretics, disloyal to Pope Francis, and just plain stupid, appear to be mean spirited and somewhat anti-intellectual. Those who accept the five dubia as legitimate questions also come across as being harsh, with similar name-calling against the other side. Whereas the Cardinals in their questions and analysis seem calm and respectful. A modicum of light humor might create more “light” than “heat.”

When it comes to ordinary temptations of the flesh, being able to run away from these temptations of concupiscence by placing in the mind and imagination cartoons, comedies on YouTube—such as Laurel and Hardy films—can more easily defang these upsurges toward carnal pleasure by filling the heart and mind with innocent humor and laughter, and preventing one from falling into fantasies of lust. Temptations are not sins, and can become occasions of growing in virtue.

Finally, if it is the nature of human beings to laugh—and Jesus Christ was true man, as well as true God—it can only be concluded that he laughed from time to time. While we are on the road to heaven—and Jesus is the “Way” to heaven—then it is necessary for our salvation to imitate Christ’s virtues in our state of life. While his love and mercy were present in his suffering on the cross for sin, it must not be forgotten that he was filled with a plenitude of virtue. And one of the small virtues is the ability to occasionally laugh, when called for, and enable others to laugh, as well.

Fr. Cole’s point in the final paragraph of this very excellent article reminded me of something Chesterton discusses in his masterpiece, Orthodoxy:

“Joy, which was the small publicity of the pagan, is the gigantic secret of the Christian. And as I close this chaotic volume I open again the strange small book from which all Christianity came; and I am again haunted by a kind of confirmation. The tremendous figure which fills the Gospels towers in this respect, as in every other, above all the thinkers who ever thought themselves tall. His pathos was natural, almost casual. The Stoics, ancient and modern, were proud of concealing their tears. He never concealed His tears; He showed them plainly on His open face at any daily sight, such as the far sight of His native city. Yet He concealed something. Solemn supermen and imperial diplomatists are proud of restraining their anger. He never restrained His anger. He flung furniture down the front steps of the Temple, and asked men how they expected to escape the damnation of Hell. Yet He restrained something. I say it with reverence; there was in that shattering personality a thread that must be called shyness. There was something that He hid from all men when He went up a mountain to pray. There was something that He covered constantly by abrupt silence or impetuous isolation. There was some one thing that was too great for God to show us when He walked upon our earth; and I have sometimes fancied that it was His mirth.”

A sense of humor might be a result of salvation.