“Let us go on to the nearby villages that I may preach there also.”

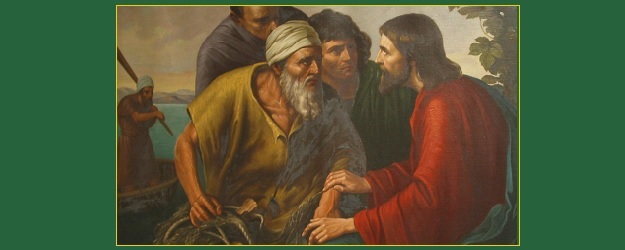

Christ and the Fishermen (Zebedee, James, and John) by Ernst Karl Zimmermann, 1852-1899

Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time—February 4, 2018

Readings: usccb.org/bible/readings/020418.cfm

Jb 7:1-4, 6-7; Ps 147:1-2, 3-4, 5-6; 1 Cor 9:16-19, 22-23; Mk 1:29-39

“For this purpose have I come.”

Why are you here?

There are obviously many layers of possible interpretation with a question like that: why are you looking at HPR right now? Why are you in the place where you happen to reside? Why are you in your marriage or religious vocation? For that matter, why are you on this earth, anyway?!

As the questions get broader, the stakes get higher. Every one of us wants to believe that there is a purpose for why we’re here. And while we might answer something like: “I’m here because God desires me to be here,” it’s not too likely that such a response is what consciously drives us on a busy Monday morning, or struggling to get the kids to soccer camp, or wrestling with a painful family situation, or settling down for some quality time with a person we deeply love. We tend to be a purpose-driven people, and, all too often, we allow our purpose to be defined by others—by other people and other things. And the purpose we have is often determined by the roles we play as we move throughout our lives. Sooner or later, such an externally-driven purpose is going to fail us— relationships will sour, good fortune will fade, success will falter. A life without a clear sense of purpose leaves us in a spiritual wasteland.

Job was a very purposeful man—at least initially. Before we meet him in today’s reading, at the beginning of the Book of Job, he is a man with a clear mission and purpose. He does well for himself and his family. He cares for his property and is attentive to his religious duties, offering prayer and sacrifice for himself and his family every day. One can imagine that Job would have told you his purpose in life pretty readily if you had asked. But then everything changed. All of his external blessings, and each of the roles he successfully filled among his family and friends, were stripped away from him. When we encounter him in the first reading, he views his life (in fact, life itself) as devoid of meaning: full of drudgery and without hope. Job’s purpose has seemingly vanished along with his possessions.

In contrast to Job, we encounter Jesus today with clear conviction. There is no doubt as to his purpose in life: “Let us go on to the nearby villages that I may preach there also.” What is the source of Jesus’ confidence about his mission? To be sure, we are still near the beginning of Mark’s Gospel, when all has been going fairly well for Jesus. But even when he is less successful with the inhabitants of Israel, his sense of purpose does not waver. Perhaps the source of Jesus’ confidence lay in something that he heard, something that Job never received. Upon leaving the waters of the Jordan river after his baptism by John, Jesus was told: “You are my beloved Son.” He knew that he was delighted in; Job only knew that his fortunes—those things that had defined his purpose in life—had inexplicably diminished.

What Jesus heard from his Father is what each one of us have been told from the day of our own baptism. We’ve been told in countless prayers and hymns, by teachers and priests, in blogs and over podcasts. We’ve been told of the Father’s unconditional love for us. And yet, I’ll admit that I have plenty of days when I feel more like Job than Jesus. Why is the theological truth sometimes so ineffective at bringing us affective peace? I suggest that the answer lies in what Jesus does in today’s Gospel that is not nearly as remarkable as his healing of the sick or the expelling of demons. “Rising very early before dawn, he left and went off to a deserted place, where he prayed.” Jesus’ purposeful identity was introduced to him at his baptism, but it took root and was formed as he spent time, day after day, with his Father in prayer. He didn’t just know that he was loved, he actively let himself be loved.

The fruit of that prayer was a great interior freedom—the freedom that comes from knowing you are loved, and truly feeling it in your heart. While Job could not escape the hold of his meaningless misery, Jesus could freely disengage even from the crowds who so passionately desired to hold on to him. Only a heart that is free is able to accurately discern its true purpose in life.

If you want to know why you’re here, pray for the grace to know that you are loved. Perhaps the seemingly trite answer to the great question is the most profound. I’m here because God desires me to be here. More accurately: I’m here because God desires me.

__________

Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time—February 11, 2018

Readings: usccb.org/bible/readings/021118.cfm

Lv 13:1-2, 44-46; Ps 32:1-2, 5, 11; 1 Cor 10:31—11:1; Mk 1:40-45

“He shall dwell apart, making his abode outside the camp.”

Who knows your name, and why do they know it?

We are known by many people, and for many different reasons. Sometimes, we’re glad to be known by—family, by friends, by a prospective employer. And there are others to whom we’d like to remain anonymous—potential rivals, those who might drain our attention or energy, the IRS! But deep down in our hearts, we all have a longing desire to be truly known by someone we trust and love. The theme song for the old TV sitcom “Cheers” nailed it perfectly: “…you want to go where everybody knows your name.” If you are fortunate enough to be known in that wonderful way, it is deeply transformative.

When I was living in Washington, D.C., I would commute several times a day on their subway system, the Metro. Over time, I came to develop what I called the “Metro test.” As you might know, D.C. can be a pretty type-A personality town. There are many high-powered people in high-stress jobs making decisions that can impact millions of lives. At rush hour on a hot day (of which D.C. has many), it was not unusual to find many commuters presenting fairly serious faces, or even scowls, to the world. They were buried in their newspapers, or briefing books, and contemplating the next meeting or business trip on their agenda. But every now and then, you would see someone—clearly on their way to work, not a tourist—with the most serene look of peace on their face, or even a broad smile. Right there, crammed like a sardine in the middle of the train car, but looking as if they were in the sweetest place on earth. Whenever I would see someone like that, I would say to myself: there is a person who knows they are loved; a person who knows that there is somebody in their life who is thinking of them that very minute, who was sad to see them leave that morning, and who is anxiously anticipating their return that night when they can be together again.

In my priestly ministry, I have found that, by far, the most spiritually distressing situation we can find ourselves in is when we feel isolated or alone. Human beings can tolerate an awful lot of pain or stress so long as they feel that there is someone with them who understands their plight, and who can love them, even in the midst of the turmoil. We are wired for community, and when we are deprived of it, we are truly less than human. Every city has its marginalized population, but so also does every family, and even every parish. The community of the marginalized is fragile but large.

When the leper encounters Jesus in today’s Gospel, he asks to be made clean, to be sure. But what he is really asking for is to be included in the community from which he was originally cast out. Notice the determination behind this desire. He does not wait for Jesus to ask him: “What do you want me to do for you?” Rather, he boldly approaches Jesus, daring to cross the great divide, and beginning to forge a new communion on his own. His very act of declaring to Jesus that he has the power to heal him is the very act by which community is born. It should be little wonder that, once healed, the man publicizes the matter, and spreads the news broadly. The new community of which the former leper is the founder, desires only to grow by inviting others in.

At a spiritual level, the leper has a profound lesson to teach us. He comes to Jesus and presents to him directly the depth of his painful isolation, and the depth of his desire for return to community. That is the purest form of prayer. We often make the mistake of praying in a roundabout way that never directly names, to Jesus’ face, precisely what is in our heart. The leper makes no assumption that Jesus “probably already knows” what he is thinking, and neither should we. Wherever we are feeling isolated and nameless—in our broken relationships, in our failed commitments, in our unrealized dreams, in our moral disappointments—we need to boldly let ourselves be known by the only one whose love can break through the isolating wall around our hearts.

So while everyone, from your credit card company to your internet provider, might know your name, the one who most purely desires to know it (and to know you) is the one to whom you freely choose to reveal it.

“Lord, if you wish…” “I do will it.” And you no longer need to be alone.

_________

First Sunday in Lent—February 18, 2018

Readings: usccb.org/bible/readings/021818.cfm

Gn 9:8-15; Ps 25:4-5, 6-7, 8-9; 1 Pt 3:18-22; Mk 1:12-15

“I will recall the covenant I have made”

As we enter into Lent, there are many traditional spiritual exercises that come to mind: fasting, more intensive prayer, greater generosity and care for the poor, sacrificing small pleasures. But there is a practice that is one of the most powerful in the spiritual life and, yet, one of the least discussed: the exercise of memory. Our sins are rarely the product of a deep-seated desire to do evil, or to withdraw from God. Rather, they result from our forgetting just how beautiful and life-giving a rightly ordered relationship with God can be: that it can be a source of peace and calm in the midst of stress or fear; that it can provide courage and fortitude in the face of despair or shame; that it can offer a joy and gratification which undermines any sense of resentment, anger, or greed. Sin is always a power-grab for something other than an authentic relationship with God—a power grab that seemingly provides a readymade, and easily acquired, remedy for fear, despair, or anger.

God himself highlights the power of memory when he establishes his covenant with Noah. The bow in the clouds will remind the Lord of his promise to never destroy the world again. Covenants are meant to be remembered. A covenant is not a law to be enforced by guardians of justice, but an intimate offer of self to be received and embraced by another. When the covenant maker recalls his promise, the desire of his heart to which it gave rise is once more enflamed, and the relationship is deepened, not simply restored.

In proclaiming the “time of fulfillment,” Jesus is calling to mind the ancient covenant God made with His people; a covenantal relationship threading back through David, Moses, and Abraham, right up to Noah. How often over the course of his life did Jesus lament that the citizens of Israel failed to see that he was the bearer of truth, just as they had failed to heed the prophets centuries before him. He sought to remind them that his Father loved them, just as He had loved their forebears in Egypt and Babylon, and that His promise of deliverance had not wavered, even in the face of Roman oppression. The hypocrisy of the Pharisees that Jesus so often railed against was spurred on by the memory of what the Law was truly meant to protect and preserve: the beautiful embodiment of the Lord’s exclusive favor on His people—the covenant with Moses. Jesus’ mission was not to scold the Israelites for immoral behavior, but to recall to their minds and hearts an earlier love of which they had lost sight.

Losing sight of authentic love is one of the most damaging consequences of sin. Think for a moment of your “favorite” sin, the one you keep falling back into, time and time again. Can you recall what your life was like before it had such a strong grip on you? Can you recall times when you felt free from its influence? Perhaps, you struggle with lust. Do you remember when you had a relationship that was rooted in pure love, and mutual freedom? What happened to cloud the memory? Sometimes, true memories are obscured by experiences of misplaced trust, betrayal, or rejected offers of commitment. Perhaps, there is someone in your life with whom you feel perpetually angry. Well, it’s highly unlikely that you felt such anger upon first meeting them. Have you forgotten what that first impression was; what it was like when the relationship was new? What were the hopes, or possible opportunities, you were anticipating that never quite unfolded as you wished? Whenever we find ourselves wrestling with habitual sin, it’s amazing how completely we can forget that life was ever otherwise, that we were once free and capable of other choices.

An exercise of spiritual healing is the exercise of remembering. Take some time during Lent to recall your memories of life “before the fall,” whatever that means for you—before the addiction, before the infidelity, before the manipulation, etc. But don’t just treat those as dead memories—museum pieces of your mind that can only bring regrets over past joys that are now lost. Invite the Lord to accompany you as you go back. In those holier, more peaceful times, you shared an intimacy with God that you might not even have been aware of. But He was there; He was there in the authentic love, in the serenity, in the confidence, in the hope. To revisit those moments is to avail yourself, once more, of the grace that has never left, but has only been forgotten in the midst of life’s challenges. Such challenges can send us looking into other pastures, forgetting where our true Shepherd would lead us.

So this Lent, by all means give up your guilty pleasures, but don’t give up your memories. God won’t either.

___________

Second Sunday of Lent—February 25, 2018

Readings: usccb.org/bible/readings/022518.cfm

Gn 22:1-2, 9a, 10-13, 15-18; Ps 116:10, 15, 16-17, 18-19; Rom 8:31b-34; Mk 9:2-10

“Take your son,…your only one, whom you love”

Do you have the courage to slay the God who doesn’t exist?

Human beings like to create gods, and we’re pretty good at it. Every primitive mythology that ever existed had a full host of gods in all shapes and sizes, each responsible for various important characteristics in the world: love, thunder, creation, etc. Christians, of course, know otherwise. We know there is but one God. We know that He is love, and that He bestows that love unconditionally upon us. And we know many other truths about Him, besides that. … Or do we?

I would argue that we are pretty good at creating false gods ourselves—or at least a false “God”. And let me be clear: I’m not talking about the fact that we can often make other persons or things in our lives into de facto gods, who consume our attention and devotion. Those are relatively easy to recognize, and Lent is a perfect time to expose them, and seek the grace to be free from their influence.

No, I’m talking about a false God who is much more difficult to identify, because at first blush, He has all the attributes of the one, true God who Is. Let me offer a childish, but telling, example. When I was a boy, I wanted a pony in the worst possible way. I had been taught (and earnestly believed), from my first day of religion class, that if I asked, I would receive. God loved me wholeheartedly, and would always do what was best for me, and I should do my best to love Him, and to behave as I knew He wanted me to. I had no reason to doubt that the pony would be good for me, and I knew that I was doing my best to be good. After all, God didn’t expect perfection, right? And so I prayed for that pony. And I prayed. And I prayed some more. And day after day, week after week: no pony. I can’t pinpoint the day or the hour, but I recall that even as a child, I started being skeptical about this whole “God thing.” I wouldn’t say that I ever doubted God’s existence, but I started wondering just how relevant He really was in my life. As I got older, there were much more serious things than ponies that I would pray for (healing of painful family situations, freedom from addictions, favorable vocation choices, etc.), and I didn’t necessarily find that God was behaving as I knew He “should.”

Many experiences can lead to our developing a sense of a false “God.” Growing up in a household ruled by judgmental, domineering parents can result in a God who is angry, and always disappointed by our best efforts. Conversely, a life that is “charmed,” in which our every desire is indulged, and we benefit from the good fortune of others, can produce a God who is little more than a benign Santa Claus in the sky, who would never ask of us a serious sacrifice, or to let go completely of our possessions. Bitter disappointments, or unrealized dreams, can hatch a God who simply doesn’t care, and certainly doesn’t love unconditionally.

Our readings today are all about revealing the one, true God as he truly is, not how we imagined (or wanted) Him to be. On the mountain with Jesus, Peter, James, and John learned that there was a quality of their friend and teacher which they had never imagined in their wildest dreams. And they were left having to decide whether or not that vision was real. And if it was, then they could never think about Jesus in the same way again. They would have to learn anew what this man was all about. They would have to accept him on his own terms. Similarly, Abraham had to face the fact that the God who had promised he would be the “father of many nations,” was now asking him to sacrifice his only son—to kill the “one whom you love.” If Abraham were to accept that this really was God, then there was something about this God that he had not glimpsed before.

One of the most difficult spiritual tasks is to unmask any element of a false god that might be lurking in our hearts. That god does not really exist, and he must be slain. Our Lenten practices of prayer and sacrifice can be powerful tools to expose what is false, and reveal what is true. Most importantly, we should pray for the grace of courage in facing the fear which whispers that if we kill the false god, then we will be left utterly alone and without any god at all.

Slay the god who doesn’t exist, and be embraced by the God who does.

Can we clone you?

We need more priests who speak the truth.

We need more priests who speak the truth about same sex attraction.

This website has been very helpful:

http://www.couragerc.com