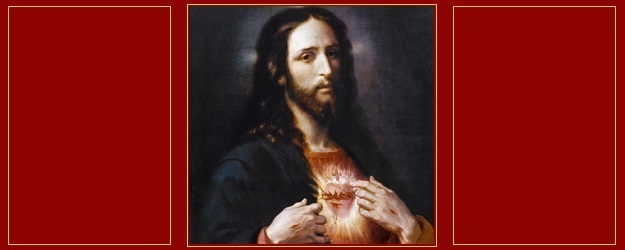

For millennia, the human heart has served as a living sign of love and affection. For the Greeks, the heart—or kardia—was where the nerves of all sensate animals met; but in humans, it was also the place where the soul enlarges, “when it desires to attract what is useful, clasping its contents when it is time to enjoy what has been attracted, and contracting when it desires to expel residues” (Galen, d. 210 AD). For the ancient Hebrews, the heart, lebab, was where Yahweh scrutinized the integrity of his people: The Lord searches the heart (1 Sam 16:7); it is the collection of one’s actions and desires, the seat of moral character. Innocent Job, for example, knew that his heart would not reproach him (Job 27:6) while carousing and adulterous David’s heart accused him of grave sin (2 Sam 24:10). In the people who arose from the Lord’s first chosen people, Christianity made the heart the place where the beloved disciple could lay his head (Jn 13:23), the place which only the mouth can reveal (Mt 12:33-34; Rom 10:9), and precisely where the waters of Baptism, and the blood of the Holy Eucharist, poured forth from the Cross (Jn 19:34).

As this people grew, their Church was blessed with more systematic and liturgical ways of reflecting on the perfect Heart of humanity. Historically-speaking, the earliest such expressions we are aware of regarding devotion to Christ’s Sacred Heart are found relatively late in Church history. The early Church Fathers did comment widely on the blood of Christ gushing from his side as a sign of the precious chalice we receive at Mass; they also had particular ways of looking at both the Passion of Christ, in general, and the particular acts and wounds of the Holy Triduum, in particular. But the heart of Christ as an object of devotion arose more in Rhineland (along the Rhine River in western Germany) in the 13th century.

What is most provocative in this genealogy is how it is mainly women mystics who exhibited very early this love of Christ’s sacred humanity, and his wounded body, in particular. Holy women—like St. Gertrude, Mechtild of Helfta (d. 1298) and St. Lutgarde of Belgium (d. 1246)—were blessed with experiences focusing their hearts on Christ’s inviting them to see a love so tremendous that it longed to suffer for the Father’s other children. This is a fitting start to a devotion that requires comfort with corporality, and attentiveness to embodiment. With the German mind, these Rhineland saints were a people who had always been able to see God in the earthiness of matter, and were never ones to shy away from the woundedness of the human body. As women, they were blessed to be more innately attentive to the other, to be able to gaze upon the other with care, and with that maternal desire to remedy the bodily sufferings of another without any taint of lust, or hint of curiosity.

It should be of no surprise, then, to learn that in December 1673, Sacred Heart devotions, as we think of them today, came into clearer vision with the mystical experiences of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, V.H.M., lasting on and off for the next two years. During the Octave of the Feast of Corpus Christi in 1675, Christ appeared to Margaret Mary revealing to her the essence of what these visions of his heart and passion had meant, and should mean now, for the whole world. On June 16th of that year, St. Margaret Mary reports how Christ appeared to her with his heart aglow and said:

Behold the Heart which has so loved men that it has spared nothing, even to exhausting and consuming Itself, in order to testify Its love; and in return, I receive from the greater part only ingratitude, by their irreverence and sacrilege, and by the coldness and contempt they have for Me in this Sacrament of Love. But what I feel most keenly is that it is hearts which are consecrated to Me, that treat Me thus.

Therefore, I ask of you that the Friday after the Octave of Corpus Christi be set apart for a special Feast to honor My Heart, by communicating on that day, and making reparation to It by a solemn act, in order to make amends for the indignities which It has received during the time It has been exposed on the altars. I promise you that My Heart shall expand Itself to shed, in abundance, the influence of Its Divine Love upon those who shall thus honor It, and cause It to be honored.

We are the graced recipients of this message, we who also gather on the Friday after the Octave of Corpus Christi because of Jesus Christ’s plea from heaven. Like Margaret Mary, to whom those words were addressed, we, too, are members of the same mystical body to which Margaret Mary, Gertrude, and Mechtild of Helfta, all belonged—the same apostolic body of Peter, James, and John, and the very same mystical body from where this heart comes, in whom this heart still beats, Jesus Christ, the now enfleshed, human Son of God. This is the Church, this is our truest identity, extensions of the incarnation bringing his very Love into our world and homes today.

In asking Margaret Mary for a feast of reparation, the Sacred Heart was entrusting himself to the movements of the Church, and with this very simple nun from Paray-le-Monial, the Church began to institutionalize and ritualize this devotion.

Along with her Jesuit spiritual director, St. Claude Colombiere, Margaret Mary is considered an essential figure in the French School of Spirituality, a 17th and 18th century type of theology and prayer centered on the sweetness of Christ’s divine humanity, and his desire to extend his incarnation in each of us. This type of spirituality includes such great theologians as John Eudes and Cardinal Bérulle, Louis De Montfort, St. Francis de Sales, and often, St. Thérèse of Lisieux is included, as well.

The French soul continued this love of Christ’s heart as the place where we could navigate the two tendencies plaguing French Catholicism in the 1600s and 1700s: Jansenism and Quietism. Jansenism is a heresy that is rigorous and uncompromising: arguing that only a few will enter the Kingdom of God, and to ensure one’s salvation, all humanity has to be eradicated, and all imperfections abolished, before one could even think of drawing near to Christ. Life for the Jansenist is one of self-determination and rigor; its theology is basically a Catholic version of Calvinism—which was harsh, stern-minded, and believed in predestination—which emphasized the failings of humanity over and against the tender and ever-merciful Christ.

The other extreme common in this belief system was “quietism,” where the believer becomes a refuge unto oneself—a form of spirituality that was recognized by a desired union with God marked by stillness of soul, and a relationship with the divine, which seemed to circumvent any need for the Church, the scriptures, or the sacraments. While polar opposites in temperament and worldview, similar to the Jansenists, the Quietists, on the other hand, tended to aim their focal point of humanity into something else—the Jansenists enwrapped the humanity of Jesus into the perfect divinity of Christ, almost embarrassed by its human condition. The Quietists, however, enveloped Christ’s humanity into the transcendence of God, not embarrassed but practically dismissive of the myriad, and very tangible and concrete ways, the divine meets us in the person of Jesus Christ.

While these two extremes are usually opposed, they both shared in their renewal of an ancient heresy, Monophysitism—a theory in which the humanity of Christ was diminished because of the awesomeness of his divinity. The Monophysite mind had a terrible time trying to maintain the tension existing between Christ’s humanity and His divinity. So, the Monophysite tended to absorb Christ’s humanity into His divinity. One sees it today in over-formality during liturgy, in a discomfort in speaking deeply about matters of the heart and, at times, in the way we tend to place law over love, and religious duties over relationships, which might challenge, or not fit, our preconceived categories of how God is present to us.

Within such harshness arose the spirituality of the Sacred Heart, as well as devotions to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. These new devotions provided the Christians a center, a place to focus their gaze outward, and against the Quietists, as well as a straightforward and childlike symbol of love and tenderness and forgiveness, in contradiction to the theories of the Jansenists.

The following century, in 1856, Pope Pius IX instituted an obligatory Feast of the Sacred Heart. One hundred years from that very day, Pope Pius XII issued the first-ever encyclical on the Sacred Heart, Haurietis Aquas, which takes its title from Isaiah 12:3: “With joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation.”

After Vatican II, the Church updated the Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy (sections §166 & §172), where we now read that:

The term Sacred Heart of Jesus denotes the entire mystery of Christ, the totality of his being and his person… Devotion to the Sacred Heart is a wonderful historical expression of the Church’s piety for Christ, [calling] for a fundamental attitude of conversion and reparation, of love and gratitude, apostolic commitment and dedication, to Christ and his saving work.

In the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church, there is only one direct reference to the Sacred Heart. In section §478, we read that:

Jesus knew and loved us each and all during his life, his agony and his Passion, and gave himself up for each one of us: “The Son of God. . . loved me and gave himself for me.” He has loved us all with a human heart. For this reason, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, pierced by our sins and for our salvation, “is quite rightly considered the chief sign and symbol of that. . . love with which the divine Redeemer continually loves the eternal Father and all human beings” without exception.

So, as we look over this history, we see that the heart of Christ stands as the Christian image of a love that gives itself for you, a love that is still pierced by our sins, but that never ceases beating with compassion and care for all human persons as we are right now.

As my Jesuit brother Fr. Ronny O’Dwyer, SJ likes to say when preaching: “That’s the so, here is the so what!”

Of all the beautiful ways we humans stay alive, none are so monitored as our heart. It is a silent, yet incessant nurturer of life. It beats on average anywhere from 50-90 times per minute and. over the course of the average American life, it will have performed this function approximately 38 million times a year for an average of 43 billion beats. if you live to be 80 years old. Of course, other organs move, other organs bring us life, but none like the heart. It is placed nearly at the very center of our being—the cor, Latin for “heart”—and is the new term used by all sorts of health professionals for strengthening us, and for keeping us upright as long as possible—the Cor.

The heart beats continuously, synonymous with one’s physical life, the metric of one’s material well-being. Like God’s grace, the heart pulsates through every single moment of our lives, most often unnoticed and unappreciated. It is literally our life line, our initial vital sign, over which we humans have no ultimate control, but can only tend and protect what has been given us. Like grace, the heart is always there, under the surface, vivifying and, eventually, deifying each one of us, giving us the capacity for infinitely more. “Without me, you can do nothing” (Jn 15:5), we hear both from inside, where we depend on this throbbing flesh to keep us alive in this world; and from outside, where we hear Christ remind us, over and over again, that all is gift, all is grace. This is the mystery of being a creature: that out of nothing, we come into being, and at every moment, we teeter between the fullness of the only Real Being who created us, and all things, out of the non-existence which is also still each one of us.

Nothingness is ours when we refuse to live as our healthiest self. If we accept, we live totally on this gift, this capacity for life which every creature is offered. But if we instead grasp at this gift and try to seize it for ourselves, then in our sinfulness, we will die because we are unwilling to surrender; we live on what is not truly life. Instead, we want to live on our own, to be the source of our hearts’ pulsing. We want to be our own sovereign, our own savior. It is infinitely easier not to have to pay attention to the millions of hearts around us, to notice that they, too, are fragile, and subject to the gift of life outside of themselves. We want to win by refusing God’s gift of Himself to us; but another heart reminds us that to win truly, is to be defeated.

God longs, therefore, to take our hearts, and make them his own, to let his heart beat in perfect unison with each of our hearts, and slowly let the two become one, beating in tandem so his total gift of self becomes each of our gifts of self, his life of love becomes each of our vocations to love. The pulsating of Christ’s heart should be the rhythm to which each of us also hear our life’s breath; but truth be told, we can avoid this melody, and choose to live off key, to move clumsily to the plodding steps of each of our own plans and prejudices. These limitations may not be correct, but at least they are our own. Is our emptiness really more alluring than his fullness?

But the paradox of this month’s feast is that precisely in not possessing Christ’s heart, we are each able to receive it; in not being God each of us can image him; in only coming from God, we can each return to him. But all of this is true only if we surrender and stop resisting this invitation. We simply have to trust that his heart is greater than ours, more noble, more loving, wiser, and more pure. Only then can we see the sense of surrender, only then will we allow his heart to beat in place of our own heart. Only then can we allow a Savior into our lives, and together with Christ, our hearts can finally beat in unison before the Father. For this is precisely what was presaged in the opening lines of Genesis: our hearts are made in the image and likeness of Father, Son, and Spirit, and only when our heart is taken up by the Son, who for our sake took on a human heart, will we finally know peace, truth, integrity, purpose, and joy. Only then, can our restless hearts know the infinite fullness for which we were brought into being.

Like time itself, the heart beats in an unnoticed current. Under the surface, our Creator has planted it deeply within so it would go unrecognized, but it was never meant to have gone undiscovered. Our hearts’ desires are where the Sacred Heart of the Lord speaks to each of us; our souls become the stages on which the divine drama is played out. We shall look from heaven onto the earthly life each of us has led, and see how our Eternal Father had provided the sumptuous banquets of our lives—the joys and the trials, the feasts and the fasts—are all watched over, and sustained by his care, and his one desire that we all choose to be with him, and one another, forever. This is why each of us matters, and matters eternally—our histories, our homes, our friendships, and our experiences. Each of our embraced vocations in life—single, married, consecrated celibate—are the ways God delights in the hearts he has created.

But this can never be an excuse to be presumptuous; it is a call to take each moment of our days as the place where God speaks to us, gently and softly, and the place where we speak to him, thanking him and growing comfortable with his presence deep within us. How often the Psalmist promises us that if we trust the Lord, he shall grant us the desires of our hearts (Ps 20:5; 21:3). We are his heart, we are the Father’s gift to his Son:

Father, they are your gift to me. I wish that where I am, they also may be with me, that they may see my glory that you gave me, because you loved me before the foundation of the world. Righteous Father, the world also does not know you, but I know you, and they know that you sent me. I made known to them your name and I will make it known, that the love with which you loved me may be in them and I in them (Jn 17:24-26).

This is the Church, this is the Body of Christ, when all created hearts beat in perfect rhythm with his Divine Heart, when all flesh is docile to the Holy Spirit, and finds, in adoration and praise of God, and perfect love of neighbor, our ultimate and final vocation, to become saints.

This is why Christ gave us one another, why he has entrusted the heart next to you to you, why he gave us his Church. The Church is Christ living in you, as you. The Church, is where his heart becomes one with yours. This Church dwells on many planes: in heaven victorious, in purgatory in waiting, and on earth still on her pilgrim way.

Let us now conclude with a look at Pope Francis’ most recent statement, the beautiful Apostolic Exhortation entitled: Gaudete et Exsultate—Rejoice and Be Glad, subtitled: On the Call to Holiness in Today’s World (hereafter, GE). It is 177 short sections long—just a bit over 100 pages, and would make for excellent summer reading! Gaudete et Exsultante is divided into 5 chapters: (1) The Call to Holiness, (2) Two Subtle Enemies of Holiness, (3) In Light of the Master, (4) Signs of Holiness in Today’s World, and (5) Spiritual Combat, Vigilance and Discernment.

While Sacred Heart Devotion is not the purpose of this Exhortation—it is not even directly referenced—yet, one cannot address holiness without at least some references to the loving Heart of Christ. Remember how Sacred Heart Devotion arose in early modern France between the two extremes of Jansenism and Quietism? Pope Francis updates these two subtle enemies of holiness, referring them to Neo-Pelagianism—which is just a modern form of Jansenism; and, a new Gnosticism—which, as we shall see, is a modern age reinvention of Quietism.

Pope Francis condemns a heresy which arose first in the fifth century when a hard-working Celtic monk fled the sacking of Rome in 410 and found himself on the safe shores of North Africa, under the leadership of Augustine of Hippo, the Church’s Doctor of Grace. Pelagius fasted and never slept, he kept his moral life pristine, and tried very hard never to give into a temptation. Consequently, he found Augustine’s insistence that all is grace, and that we can do only what God gives us the power to do, was a sloppy excuse for imperfection, and contentment with the status quo. Pope Francis picks up on this tendency in the self-righteous, and writes today that, those who:

even though they speak warmly of God’s grace, “ultimately trust only in their own powers and feel superior to others because they observe certain rules, or remain intransigently faithful to a particular Catholic style” (Evangelii Gaudium §94)… Ultimately, the lack of a heartfelt and prayerful acknowledgment of our limitations prevents grace from working more effectively within us, for no room is left for bringing about the potential good that is part of a sincere and genuine journey of growth (Evangelii Gaudium §44). Grace, precisely because it builds on nature, does not make us superhuman all at once… Unless we can acknowledge our concrete and limited situation, we will not be able to see the real and possible steps that the Lord demands of us at every moment, once we are attracted and empowered by his gift. Grace acts in history; ordinarily it takes hold of us and transforms us progressively (GE §49-50).

It is important for us to remember that the subject of John 14:6 is not a doctrine or a dogma, it is a living person, Jesus Christ, who entrusts his Sacred Body and Blood to his Church, and this Church will always judge me; I don’t judge her. This Church will always be larger than my own limited perspectives, and more savory than my own particular tastes.

The other extreme that Pope Francis sees as a threat to the holiness to which we are all called in the 21st century is a form of Gnosticism. Ancient Gnostics believed in a world that was the result of warring powers—one eternally good, and the other co-eternally malevolent. These two at one point intermingled, giving rise to a hostile world, torn between good and evil, spirit and body, men and women, the learned and the unwashed. The fear of today’s Gnosticism, according to Francis, is that it removes the Gospel from the concrete realities of most everyday Christians; it instead becomes an intellectual exercise apart from the demands of what it means to be embodied—to be hungry, lonely, and searching. It threatens the unity of the human person, body and soul, as well as the Church where saints and sinners—those still seeking, and those already blessedly assured of Christ’s power to heal.

Against the Pelagian worldview, holiness is always other-centered, a matter of the relationship Christ calls each of us to. Against the Gnostics, holiness always demands care for the whole person, the whole community, and not an escape into abstract thought, or some sort of ethereal spirituality. Holiness demands a heart, an enfleshed and beating love, which is pure enough to see God.

That is why Pope Francis next takes us to the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, where Jesus himself lays out what it means to follow him, to become him! To be merciful and to be wise, to cry over the injustices of this world, and to hunger for a fulfillment no political regime, or earthly strategy, can bring about. But above all, it is to have a heart filled with the divine life so as to love our neighbors as God himself loves them. As Pope Francis writes, the Beatitude of the Heart,

speaks of those whose hearts are simple, pure, and undefiled, for a heart capable of love admits nothing that might harm, weaken, or endanger that love. The Bible uses the heart to describe our real intentions, the things we truly seek and desire, apart from all appearances… (GE §83) Certainly, there can be no love without works of love, but this Beatitude reminds us that the Lord expects a commitment to our brothers and sisters that comes from the heart. For “if I give away all I have, and if I deliver my body to be burned, but have no love, I gain nothing” (1 Cor 13:3). In Matthew’s Gospel, too, we see that what proceeds from the heart is what defiles a person (cf. 15:18), for from the heart comes murder, theft, false witness, and other evil deeds (cf. 15:19). From the heart’s intentions come the desires and the deepest decisions that determine our actions (GE §85)…Keeping a heart free of all that tarnishes love: that is holiness (GE § 86).

The heart was created by God in the Garden as a cause of human living, and as a sign of his ever-present closeness. It is the heart he reads, scrutinizes, and whose desires he longs to honor. The heart was assumed by the Second Person of the Trinity, in the womb of a virgin woman, young and scared and seemingly alone in a world that could have condemned her to death if another creature had not trusted the Holy Spirit to serve the heart beating in her womb as foster father and protector. Both hearts, the Immaculate Heart of this woman (Lk 2:35) and the Sacred Heart of this Son (Jn 19:34) were both pierced and laid open as they lived these years in this fallen world.

A heart capable of love, as Francis expresses it, must be one of true Christian sincerity. This does not mean that we be dour and ever serious. It means we let ourselves be renewed daily as children, as those invited into the Father’s family, so as to live this life without any harshness or insecurity, no mean words, no vying for an attention we receive only at the expense of another, no competing for love and care. On the contrary, it means having the heart of a beloved son, the heart of a beautiful daughter. For only when one knows deeply that he or she is loved perfectly and eternally, as you are, and not as you imagine you have to be, can the harshness and envies we harbor cease. Only in knowing that we are the Father’s own can we bring that love to others without strife, or the need to win, and always come out on top.

Take my Heart into you, for it is meek and humble, our Lord invites us. Take that Heart, receive him in the Most Holy Eucharist daily, so as to live anew, die to the stone within you, this false image of who you are. Let the pierced Heart of Christ break open your heart now, and at each moment. Live tenderly, and with the Truth that God is real, and this life is our first step into heaven. For you are the beloved, the chosen one, whose baptism has made you new, and whose human heart was made to become Christ’s own Sacred Heart.

Enjoy a blessed summer,

Fr. Meconi, S.J.

In my opinion, commitment to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is on the wane. Do you agree? And if you agree, could you, please, offer an explanation for this sorrowful state of affairs?

Thank you very much for an inspiring and moving read, carefully reread and printed for future pondering.

There are many heighten moments on this written work on the Sacred Heart of Jesus. One the second Vatican council update on the populous piety and liturgy on the devotion to the Sacred Geart and two,

Pope Pius x11 quote from Isaaiah which says’ with joy we shall draw water from the wells of salvation.’

Taking up pope Pius the x11. Understanding that the sacred heart of Jesus goes beyond the limited scope and confinement of the saving presence of God to our human conception of what the heart is and is not. You did point out the dichotomies between law and love between duty and relationship with God which is the problem that keeps us from drawing water from the well of salvation.

We need to keep singleminded focus on the presence of God . God who was revealed in time ,lived among men , he spoke ,taught ,work miracles and set an example or way of life that leads to salvation.

If I were to show true devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus it would be to keep my focus my intent my search my desire for what is true real freeing and life giving.

I agree with Pope Francis it is about being in the moment well disposed to a good will and keen mind set to move in mercy and compassion in relation to others . To live in a state of mercy and consecrated to the mercy of God is indeed the water drawn from the well of salvation.

Thank you.