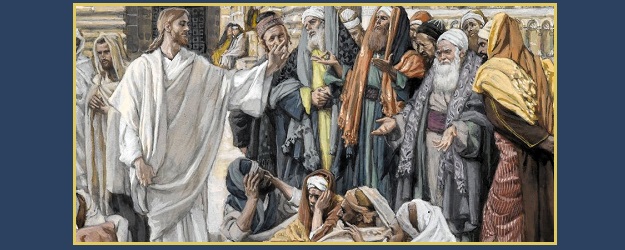

Artwork by Tissot

One of the many mysteries in the New Testament is the reaction of the Pharisees, when Jesus of Nazareth restores a man’s withered hand on the Sabbath. This was in the first year of his miracle-packed ministry in Galilee, but he had already given grave offense. Earlier, he cured the pallet-borne paralytic in the house in Capernaum, uttering the blasphemy, “Your sins are forgiven,” to which, the Pharisees rightly objected, “Who can forgive sins but God?” Then, a Sabbath or two later, Jesus meets the man with a withered hand in the synagogue.

The Miracle Worker was now under the eyes of Pharisees from Jerusalem, checking him out – as was their duty. “They watched him, to see whether he would heal him on the Sabbath” (Mk 3:2-6). So Jesus asked them, “Is it lawful on the Sabbath to do good or to do harm, to save life or to kill?” They were silent, and Jesus looked at them with anger, “grieved at their hardness of heart” – one of the select few times we’re actually told his feelings. Jesus tells the man, “Stretch out your hand,” and “his hand was restored.” Here comes the shocking part. Having just seen the truly miraculous, the restoration of a withered hand, “the Pharisees went out, and immediately held counsel with the Herodians against [Jesus], how to destroy him.”

These Herodians were the ever-watchful secret police of Galilean King Herod Antipas, a younger son of blood-soaked Herod the Great. The father, crowned by the hated Romans, had been responsible for the wholesale massacre of tens of thousands of rebellious Jews (and incidentally ordered the Holy Innocents murdered – retail butchery.) Herod Antipas was not his father’s equal as a fun-loving executioner, but there was a revolt while Jesus was growing up in Galilee, which young Herod resolved by crucifying two thousand rebels – downwind of his capital at Zippori, but upwind of Nazareth, four miles away (Frank Sheed, To Know Christ Jesus). This is the Herod who married his niece and brother’s wife, Herodias, and later imprisoned and beheaded John the Baptist for criticizing this.

Herod Antipas was neither a pious Jew nor Righteous Gentile, so for the Pharisees to “hold counsel with the Herodians… how to destroy him,” seems almost beyond comprehension. These days, it would be like half-naked feminists holding counsel with hijabbed Sharia Muslim women on how to overthrow the patriarchal West… as happens increasingly at the Women’s Marches and UN conferences. There is a mystery here, recurring across 2,000 years.

Weeks earlier, Jesus uttered the appalling words, “Your sins are forgiven,” and no-one stoned him then. If they weren’t enraged by his claiming authority over sin, why the rage with his claiming authority over the Sabbath? The Sabbath was the issue.

The Mystery of the Sabbath

The mystery of the Sabbath has niggled at the back of my mind for forty years, ever since I first encountered Nietzsche, insisting on Europe’s great debt to the Jews for inventing it. The irony is, I got it wrong. That’s not what Nietzsche said. In Beyond Good and Evil no.189 (Kaufmann trans.), he actually says: “Industrious races find it very troublesome to endure leisure: it was a masterpiece of English instinct to make the Sabbath so holy and so boring that the English begin unconsciously to lust again for their work- and week-day. It is a kind of cleverly invented, cleverly inserted fast, the like of which is also encountered frequently in the ancient world…”

The topic is the Sabbath, yet the Jews don’t rate Nietzsche’s mention. He doesn’t refer to the Jews until aphorism no. 195, where he describes them as either “a people born for slavery, as Tacitus and the whole ancient world say,” or “the chosen people among peoples, as they themselves say and believe.” Contrary to my bad memory, Nietzsche doesn’t speak of “What Europe owes to the Jews?” until no. 250, where he answers his own question: “Many things, good and bad, and above all one thing that is both the best and the worst: the grand style in morality, the terribleness and majesty of infinite demands, infinite meanings, the whole romanticism and sublimity of moral questionabilities… the sky of our European culture.”

First, I must reassure the reader that this is not an exploration of Nietzschean philosophy, but rather wrestling with the meaning of the Sabbath. If there is an excuse for bad memory, it lies in Nietzsche’s all-too-typical habit of setting his premises in riddles. Why did he play this game, discussing the Sabbath without mentioning the “most industrious” Jews? But then, why did the Sabbath violation so enrage pious Pharisees that they allied with despicable Herodians? Let us rush to the “bottom line,” sketching a concluding formula (like the punch-line of an endless joke), before unpacking the process of discovery that may put flesh on its bones.

In conclusion: the Sabbath meant that ordinary Jews could not be drafted by their rulers into work gangs for at least one day each week. The humblest Jew had that nugget of personal autonomy. So they could not be truly enslaved as chattel by their own rulers. Their identity as members of the tribe therefore could not be mediated by their rulers (or “ummah”). On the Sabbath, confessing Jews were encouraged to contemplate personally and individually the God of Abraham, the “I AM” of Moses. This empowered Jewish peasants to stand in judgment of their rulers (as prophets), whenever their rulers fell short of the law. This meant the tribe could survive – and repeatedly did survive – the destruction of its ruling elite. Ironically, it also meant that the Jews could be enslaved “as a people” without dissolving into a conquered, deracinated mass. Hence Nietzsche’s joke: the Jews were both the chosen people and “a people born for slavery,” uniquely enslave-able as a people.

The Democratization of Contemplation

How could a “statutory holiday” have such profound effects? In his majestic little study, Leisure: the Basis of Culture, philosopher Josef Pieper argues that all real holidays are not merely breaks from “the world of total work,” but rather holy-days. Our so-called “civic holidays” may be intended for “sleeping in,” resting for tomorrow’s work. But real holidays are necessarily religious festivals, uniting a community with its animating divinity. Contrast “Earth Day” or “Labor Day” with Christmas, Easter or even Halloween. The market has worked tirelessly to convert our real holidays into quarterly clearance sales, but even this proves the expectation of worship – “sacrifice” – that comes with even decayed communal festivals. We worship in the church of our choice, even if it’s the mall.

In criticizing Modernity’s “World of Total Work,” Pieper argues that “Worship is to time, as the Temple is to space.” The Latin or Greek “templum” indicates “cutting off” sacred ground from practical use. The community reserves a plot of land, sacrificed to common worship, and the fanum or temple precinct insulates everything more important – higher than us, already created before us – from the profane, profanum, everything else that is merely subject to use.

Likewise, the religious festival cuts off a span of time from workaday brambles, chattering necessity and prodding utility. When work is forbidden, then comes space for meditation, the contemplative intellect. In the face of its constant struggle with practical deliberation – “thorns that spring up and choke the seed,” the Gospel says – apparently useless contemplation claims its rights as a citizen against impatient utility. In the Parable of the Sower, “practicality” is one of the three definitive challenges to the fertility of the Word of Salvation. And this is truly ironic, since citizenship – sharing life in a common good – real citizenship exists only as shared contemplation of a concrete culture, defining the nature of the Cosmos and therefore what is truly practical for the next generation.

Post-Enlightenment ideological scientism – not science – has tried to disenfranchise “metaphysical” contemplation in favor of “practical” mathematics. But ideological modernity has only been able to impoverish our vocabulary – as if painting only in black-and-white. To the degree we still have a culture, it exists only as a shared object in the contemplation of each citizen. Humanity remains “condemned to metaphysics,” as Max Scheler said. Every culture exists in its calendar of festivals, its contemplation of its God or gods.

However (pace Pieper), not all festivals are Sabbaths. For example, the calendar of the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli obliged every temple town to celebrate a thousand human sacrifices yearly, 50,000 beating hearts torn from human chests (including one-in-five children, almost matching our abortion rate). At the dedication of the new temple of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) in 1487, 30 years before Cortes, over 80,000 people had their hearts removed by hundreds of priests, working in shifts for four days and nights (Warren Carroll, Our Lady of Guadalupe).

Hard work, that, and certainly not a Sabbath. It was not even what Nietzsche calls “the terribleness and majesty of infinite demands,” because all that it required of its victims was nor more than docile fatalism, herded by Aztec soldiers, and fifteen seconds of agony at the hands of their priests. Tellingly, Aztec culture did not survive destruction of its military and theocratic elite, though Mexico’s ruling elite still strangely celebrates Montezuma on its colorful currency.

The Sabbath is different, because on the seventh day, “thou shalt not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant nor thy maidservant, nor they cattle, nor the stranger within they gates” (Ex 20:10). This applies to everyone. However, again pace Pieper, sacred time is not simply the same as sacred space, at least not in the practicalities of “cutting it off” from mundane use. It is easy to enforce the fanum, the sacred precinct, with armed guards, but how precisely does one police someone not working? Where does one draw the line? Harvesting was work, of course, but could a pious Jew rescue a sheep from a well? Conversely, while one can hardly imagine a zealous Aztec victim – any zeal would be absurdly irrelevant – the Sabbath was an injunction almost designed to encourage debate and zealotry among the scrupulous, like the Essenes who refused to void their bladders before sunset.

The point is, the Sabbath can, practically speaking, oblige only free personal observance. This is the law that defined its tribe, but not a law capable of regimentation. So the Pharisees argued to enforce the Sabbath, but in the end, they could only witness bitterly to the varying degrees of observance – varying degrees of piety and faithfulness. They could dish the dirt on the non-observant, but there remained something intractably voluntary in tribal membership.

The Citizenship of Labor Gangs

Repentant former Marxist Karl Wittfogel argued that the natural trajectory of economically developed civilizations (ancient and modern) is Oriental Despotism: the metastasis of a sacerdotal public bureaucracy that gradually absorbs all available surplus labor, seven days a week. Egyptian or Babylonian astronomer-priests saw a great mass of peasantry standing idle betwixt planting and harvesting, so they could and did enlisted them in work levies, constructing canals and pyramids, serving the gods and keeping them out of mischief. Chinese Mandarins, schooled in public administration, enlisted their peasantry in the maintenance of their irrigation systems. Wittfogel describes these regimes as “hydraulic societies,” defined by sacred calendars of unpaid levy labor on irrigation and other public works. These societies work because they are seen to work – like the modern Public Service, and they are sacred, because their working testifies to the Order of the Cosmos.

Bureaucratic despotisms (so dreaded by de Toqueville) enjoy enormous stability, given universal and perennial dedication to their common good: visible public works. So when the Roman Empire absorbed pharaonic Egypt, Augustus Caesar was obliged to “put on the Horns of Horus,” simply to keep Egypt’s peasantry filling its granaries (and feeding idle Rome). When Mao Zedong replaced the “spindle of heaven,” rotating through Beijing’s Imperial Palace, with an equally “metaphysical” Marxism, the Great Leap Forward was an almost inevitable result of Confucian obedience. However, the piety of such tribes, though docile, is expressed solely in customary labor, obedient to a faceless, unquestionable public administration.

Such clerical public administrations remain a perennial possibility. Today, for example (at the risk of becoming topical), we have mandatory recycling programs, enlisting thousands of hours of unpaid labor in a public work of doubtful economy, “serving the Earth.” We apply the “precautionary principle” to such public works, just as the Aztecs assumed sacrificial inferences of their genuinely scientific astronomy. Our clerks or clerics again mediate our collective piety.

Humankind is indeed condemned to metaphysics. As Wittfogel outlines, the “public work” of the despotic Aztecs was fighting mock Flower Wars, in order to provide docile prisoners for insatiable temple sacrifices. This testifies indeed to the contemplative intellect’s power over the practical intellect, defining what is truly practical and nurturing the next generation. It also testifies to the contemplative intellect’s plasticity in constructing a Platonic Cave of terrifying outlines. It testifies to Fallen Humanity’s natural expectation of Divine Retribution. However, it is certainly not the piety of the Sabbath, establishing voluntary and personal contemplation of a paternal divinity, “the Lord.” It is not a personal piety.

Free Membership versus Pious Authority

We can now put some flesh on the Pharisees rage, confronted by Jesus’ cavalier attitude toward the Sabbath. As “animals with reasoned speech,” we must find meaning in otherwise empty lives, and we generally find meaning in belonging to our tribe. For most of human history, that belonging has been simple submission – even when coerced (as witnessed by the pathetically few Aztec soldiers needed to herd their victims). With the Jews and their Sabbath, however, that belonging became free, voluntary and perforce subject to deliberation and degrees of commitment. For the Jews, that meant being a priestly tribe among other tribes.

Now imagine the frustration of those truly longing for the “redemption of Israel” – the Pharisees. Were one truly longing for the Messiah, one might well expect the advent of this redemption to depend somehow on the righteousness of Israel – particularly the observance of the Sabbath and all the great feasts. Yet for most, this observance is more-or-less relaxed. Then this Miracle Worker comes along, touted as the Anointed One, and he blatantly threatens the Law of the Sabbath – which means he threatens the very existence of the tribe he is meant to save. He cannot be the Savior of the tribe that he threatens to destroy.

For a fervent lover of the tribe, there is one thing worse than the member of another tribe, even of an inveterately hostile tribe. The one thing worse is a traitor within one’s own tribe. In response to a traitor, the Pharisees might justly ally with the despicable Herodians. Likewise, today, when feminists ally with Sharia Muslim women, against traditional family women, they are not asserting greater tolerance. Their obvious “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” reflex is actually expressing the priority of tribal membership over principles and even shared, foundational interests. It is a rejection of the primacy of principle in favor of tribal membership. This is not a good thing.

We should not underestimate the pull of the tribe and its pagan gods. However, the Sabbath instituted a membership transcending servile labor, warrior obedience or priestly asceticism. The Judeo-Christian dispensation gradually elevated personal piety over tribal membership, as seen in the Righteous Gentiles or “unwalled” City of God. It permitted us to see virtue in our foes – like Churchill’s praise of the German General Rommel or American statues to Robert E. Lee – despite their adherence to an evil cause. It permitted civil political debate, since policy and piety remained open to public deliberation. However, this civility began to vanish 60 years ago, with legal challenges to Sunday “Blue Laws.” Their repeal in the name of the Freedom to Shop edged us further into the servile World of Total Work and tribal submission.

Walker Percy poses the question (The Message in the Bottle): “When one meets a Jew in New York or New Orleans or Paris or Melbourne, it is remarkable that no one considers the event remarkable. What are they doing here? But it is even more remarkable to wonder, if there are Jews here, why are there not Hittites here? Where are the Hittites?” Within a political and sociological framework, the answer is: the Hittites had no Sabbath. Within our poor, battered Western “Civilization,” it has been our malnutrition, that we no longer have a Sabbath, merely docile service in the mall of our choice.

Recent Comments