Where in any classical literature do men rejoice over wounds? In the ancients, injuries and lacerations bring about sorrow, if not revenge. But in the Gospel reading for Divine Mercy Sunday (Jn 20:19–31), we see a new understanding of vulnerability, forgiveness, and mercy. “‘Peace be with you.’ When he had said this, he showed them his hands and his side. The disciples rejoiced when they saw the Lord” (Jn 20:19–20). In rejoicing over Christ’s wounds, the Church invites us to see that there is no place that God’s love refuses to penetrate and redeem.

One wonders how many modern-day Christians still have the mentality of the ancient Gnostics, a theology wherein there are two coequally powerful deities, one good and the other malicious. To the one good god we bring all of our accomplishments and small spiritual successes throughout the week; to the other, we reserve all of our embarrassments and sins, our addictions and painful trials. Such a mind tends to equate the God of Jesus with the God who is wholly good and with whom we can share our brighter moments, but a sovereign who is often displeased with who I am and disappointed in many of the things I have done. Accordingly, there is this other “god,” this shadowy place where I put all the things I hate, the situations and experiences I don’t understand, and where I tend to store all that disappoints and brings desolation.

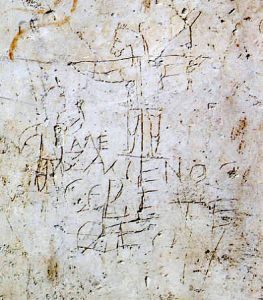

Ancient Roman anti-Christian graffito, reading, “Alexamenos worships his god.”

But the Son of God took on human flesh and embraced mortality. At her “yes,” Our Lady could give the Infinite only finitude, grant the Immortal only mortality, offer Life himself only death, and in this convergence of contraries, the Lord of All shows us his power through weakness, his judgment through mercy, and his presence as only love. This is an embrace of competing opposites that no other religion knows. It is therefore not insignificant that the first piece of material anti-Christian propaganda we know about is the famous “Alexamenos Worships His God” graffito from Rome’s Palatine Hill, dating most likely to the second century.

Here we see a simpleton named Alexamenos praying before a crucified donkey. This is a telling representation of how the ancients thought of this newly found creed following Christ: unsophisticated, unadorned, gullible, and — quite honestly — asinine. Neither Greek nor Roman could imagine how a God would draw so near to his people that he would literally take on the human condition, be reliant upon the permission of a young virgin to carry out his plan of redemption, to become so one with mortals that he could actually die an ignominious death, even death on a cross.

Nothing God Won’t Redeem

Divine Mercy Sunday gathers all of these themes together in order to remind us how there is nothing in our life our God won’t touch and redeem if we simply surrender those moments and places to him. Celebrated since 2001 on the first Sunday of the Easter Octave, Divine Mercy Sunday was robustly promulgated by Saint Pope John Paul II, no doubt inspired by his love of Saint Faustina Kowalska and her encounters with the divinely merciful Heart of Jesus in the 1930s. As such, on May 5, 2000, Saint John Paul II asked the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments to proclaim this relatively new feast as such:

Merciful and gracious is the Lord (Ps. 111:4), who, out of great love with which He loved us (Eph. 2:4) and [out of] unspeakable goodness, gave us his Only-begotten Son as our Redeemer, so that through the Death and Resurrection of this Son He might open the way to eternal life for the human race, and that the adopted children who received his mercy within his temple might lift up his praise to the ends of the earth. In our times, the Christian faithful in many parts of the world wish to praise the divine mercy in divine worship, particularly in the celebration of the Paschal Mystery, in which God’s loving kindness especially shines forth. Acceding to these wishes, the Supreme Pontiff John Paul II has graciously determined that in the Roman Missal, after the title “Second Sunday of Easter,” there shall henceforth be added the appellation “(or Divine Mercy Sunday),” and has prescribed that the texts assigned for that day in the same Missal and the Liturgy of the Hours of the Roman Rite are always to be used for the liturgical celebration of this Sunday.

Saint John Paul II’s promulgation of Divine Mercy was first expressed in his 1980 encyclical Dives in misericordia, while, closer to our day, Pope Francis announced a Year of Mercy with his 2015 Misericordiae vultus. As different as these two papal documents are, in both depth as well as in discussion, both emphasize the same theme of mercy as coming from Christ’s pitying or lamenting (miserere in Latin) heart (cor in Latin).

Note the irony: Christ can have mercy for sinners because his heart too is pitiful, it too has known misery, it too has died. The paradox of the Cross thus emerges on this Sunday in particular: we rejoice not despite our wounds but because of them. “Go and learn the meaning of the words, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ I did not come to call the righteous but sinners” (Mt 9:13). It is paradoxically freeing to be able to admit need for a Savior. But only then do we give Christ the needed permission to enter into our lives. “The truth, revealed in Christ, about God the ‘Father of mercies,’ enables us to ‘see’ Him as particularly close to man especially when man is suffering, when he is under threat at the very heart of his existence and dignity” (Dives in misericordia, 2).

Divine Mercy Properly Understood

How many of us have ever said something like this: “Would you please pray for me? I’m having a really, really . . . good day!”? Our reaching out and request for prayers does not usually follow this pattern. The opposite is true: where we too are hurting and where we too are in doubt — waiting for the results of that medical test, thinking about that perhaps painful conversation with a coworker — these are the places where we finally stop for a second and ask for the Lord’s grace and mercy.

This is why the pharisaical among us do not really know how to celebrate Divine Mercy Sunday. Like the religiously professional of Jesus’s day, they act only out of their self-righteousness, out of their own supposed superiority. They would rather condemn the impiety of others, find suspicion everywhere, and judge actions their hubris simply cannot interpret rightly.

Pope Francis writes in Misericordiae vultus:

Jesus is bent on revealing the great gift of mercy that searches out sinners and offers them pardon and salvation. One can see why, on the basis of such a liberating vision of mercy as a source of new life, Jesus was rejected by the Pharisees and the other teachers of the law. In an attempt to remain faithful to the law, they merely placed burdens on the shoulders of others and undermined the Father’s mercy. The appeal to a faithful observance of the law must not prevent attention from being given to matters that touch upon the dignity of the person.

That the Pharisees strive to keep the law is to their credit, but the fact that they think this is what makes them loveable is to their damnation.

The Gospel this Divine Mercy Sunday teaches how the Father sends his Son in “the likeness of sinful flesh” (Rom 8:20) for no other reason than to show his love for us, as one of us. This is true mercy: when a great lover not only draws near to his beloved, but also becomes one with his beloved. For only in this divine exchange, God’s humanity for our godliness, can divine mercy be properly understood. For only here does wounded humanity become a place for rejoicing, a place where the elect can finally gather, not despite their being wounded, but precisely because they are.

This first appeared in Teaching the Faith, a publication of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars. It has been slightly modified for publication in HPR.

i do not think anything more be said than what you have conveyed in this work on trusting in God and His mercy for us sinners. You captured the problem of our difficulty in not being able to surrender to the mercy of God and trust in His love to redeem us in spite of our failings perfectly. It was truly life giving.

May God be praised when his priests truly reflect His heart. May God sustain your holiness.

Thank you for expressing the Heart of Christ to us. May we now express it to others through our words and actions.

Blessings and prayers,

(served with you at The Cloisters)