The revised translation of the Roman Missal will show if attitudes and integration with daily life receive new inspiration, serving as a “sign of the times,” a litmus test of the spirit of this generation.

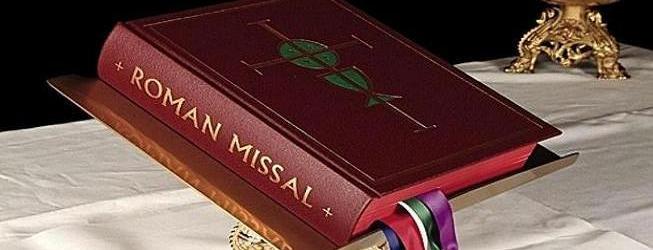

The new English translation of the Roman Missal is one of the most significant liturgical reforms in the life of the Church since the Second Vatican Council. Its effect is immediate and broad. This revision of liturgical language, likewise, intimately affects the religious experience of English speaking Catholics. And yet it is precisely this impact that affords the Church an unparalleled opportunity for authentic renewal.

One particular dimension deserving attention is the manner by which the Church receives the sacred words of the Liturgy. To simply enact the new legislation, to explain the principles guiding the method of translation, or to explain its correspondence to Christian dogma fails to exhaust the full potential of this liturgical change. This reform must be accompanied by a type of examination of conscience. Whether attitudes and integration with daily life receive new inspiration from the revised translation of the Roman Missal will serve as a “sign of the times,” a litmus test of the spirit of this generation.

The sacramentality of language

The celebration of the sacred liturgy in the vernacular was seen by the Second Vatican Council as an organic component of ecclesial renewal. While neither abrogating Latin, nor sanctioning unfettered use of the vernacular, the Council Fathers foresaw pastoral value behind wider application of the vernacular. It was noted that this “may frequently be of great advantage to the people” (Sacrosanctum Concilium §36). One aspect of this advantage is a fresh attention given to the sacramentality of language, by which I mean the capacity of language to communicate something about the mystery of God that is true, real, and meaningful.

Indeed, the revitalization of this sense of sacramentality has animated the diverse translations of the Roman Missal (and other liturgical books) since the Second Vatican Council. When language is employed in the service of revelation, it renders divine realities accessible, investing language with the power to accomplish the very redemption to which they bear witness. They enable the individual Christian, and the Church as a whole, to “speak salvation” for the sake of the world. Thus, the sacramentality of liturgical language, and the Church’s missionary mandate, are strictly related to one another.

The mission of evangelization does not mean that the Church proclaims the Kingdom of God in an impersonal way. Rather, she is sent to speak from a heart and mind that have been shaped by the mystery of Jesus Christ. This loving encounter with Christ allows her to address the deepest needs, desires, and aspirations of the individual person and society at-large. As the Church listens in faith to the proclamation of the Scriptures, and the spoken words of the Sacred Liturgy, she hears the Lord lovingly addressing himself toward these very realities. The Church confesses that, in the last analysis, they are expressive of a capacity for the sacred which only Christ can definitively satiate.

The alienation of words

By contrast, the advance of secularism has evacuated a sense of the sacred from society. It has divested language of transcendental meaning, and has labeled any search, thereafter, as escapist.

The supreme value worth living for, then, is that which can be constructed by willing it. In a globalized world, this creates an ethos of competition. If people and nations want to have a meaningful place in the world, they must market their vision as indicative of happiness. Unless one is competing and asserting his opinion, he will suffer the fate of marginalization. Thus, the horizon of society is marked by a looming sense of alienation.

The proliferation of words on the internet, T.V., and in print media, inundates the mind today, functioning as a tourniquet for the soul. Headlines and scrollbars are reduced to a minimum, so that a person may feel like he is up-to-date and can participate in society. The use of text messaging, tweeting, and instant messaging have amplified this shift. As a result, a whole new language has developed.

This evolution has led to a reversal of its aims. Language has become so casual, that it no longer arouses the soul. Wholesale conversations have become superficial. When the soul is no longer lifted up, words become a weight too heavy to bear. They tax the mind and become the bane of existence. The consequence is isolation and contempt. One is left feeling more alone than ever.

The challenge of the new missal translation

The retranslation of the Roman Missal assembles these challenges under the tutelage and function of language by boldly re-imaging the place of sacred language in post-modern culture. It stands in clear contrast to the adverse influences not only affecting language, but also in the domain of human relationships. It proposes a new cultural paradigm by subtly shaping the way many approach God. It calls for thoughtful depth in prayer, and does not permit an overt focus upon the self.

The new translation appears, from this vantage point, as an ostensible threat to the relative stability of the present translation. The advances that many lauded in the Church for a generation seem as if they will be encroached upon. The Sacred Liturgy, in this view, will become once again obfuscated. Is it any wonder that there is a fear, among some, of being separated from their past, and being pushed to the periphery of the Church? To the contrary, the new edition of the Missal is neither a rupture from the former translation, nor its sacramentality. Rather, it utilizes the former text as an organic starting point for all developments. In some cases, there is no notable change between the editions, as with the Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God…”). In other cases, new layers of reflection are added which build upon the literal meaning of the present text, such as “The Lord be with you…. And with your spirit.” These relative changes in the Missal are a capitalization upon the faith of previous generations. They provide it with a renewed sense of ineffable mystery.

In this light, the changes are an invitation for everyone to make their home, once again, in the perennial freshness of the sacred words. They endow the fragility and limitations of human language with a renewed sense of God’s “salvific speech” to mankind. Consequently, all forms of alienation, especially that arising from the transition between the Missals, find their resolution in this proclamation and epiphany of the Divine Word.

The Theocentric Nature of Liturgy

The Sacred Liturgy discloses the incommensurable “place” where the Church listens in faith to the Word become flesh. The humanity of Christ accommodates the ineffability of God’s mystery so that it might be rendered intelligible to the Church. In other words, in the Sacred Liturgy, Jesus announces the nearness of the Kingdom of God by communicating the life of the Father to the faithful. As God came close to humanity in the humanity of Christ, he continues to speak to his Church the divine word of salvation vested, as it were, in human words.

This means that the language of the Sacred Liturgy, which the Church employs, is ultimately and unequivocally the prayer of Jesus at the right hand of the Father. By uniting it to his filial perspective, through the efficacy of the Holy Spirit, Jesus orients the Church-at-prayer toward the Father. The Church, then, must always remember how blessed and privileged she is to enjoy the prayer of the Son.

This grace whereby a person is joined to the perspective of the Son, makes use of the capacity for the sacred within each person. Christ reveals this capacity for God (capax Dei) to be a capacity for the Trinity (capax Trinitatis). Such a capacity is predicated upon the heart of Trinitarian life, namely dialogue and communion.

The sacramentality of language, in this light, means that man is given the capacity and power to listen to God, and speak meaningfully with him. From this divine dialogue, emerges the desire for a new community that has a sense of the sacred at its foundation. I would suggest that the retranslation of the Roman Missal is a renewal of the fundamental call to communion. How the Church receives the new English edition of the Missal will be indicative of the end she is pursuing.

The Sacred Liturgy, in this view, will become once again obfuscated. Is it any wonder that there is a fear, among some, of being separated from their past, and being pushed to the periphery of the Church?

This idea is, of course, ridiculous. It was the post-Vatican II changes in the liturgy, and especially the English translation, we have just abolished (and to which, as I recall, nobody was given any opportunity to object), that separated us from our past, from at least fifteen hundred or so years of it. It is so silly to hear people speak of a couple of generations of tradition as though that were a significant amount of time. Of course, the objectors aren’t really concerned with liturgical appropriateness at all, but with exactly the matter that they claim to oppose. Their whole point is that they WANT to separate us from our past.

Where is the mention of the sacrifice?

Where is the mention of redemption from sin?

What about the fifty generations before this last one that, that we are no longer in continuity with?

Very frustrating. Do you really believe that this mass would win the approval of St. Alphonsus Liguori or St. Bernard?

Still the man, Fr. Schamber! Tallahassee misses you!

AMEN!!! Thank you for the eloquent way you evoke reverence for the written and spoken word…for acknowledging its power to mysteriously speak to our humanity through its divinity. As the seemingly archaic vestments of the priest signify and evoke a reverence for the mass he leads us into, so, too, does the seemingly antiquated language of the liturgy awaken our awareness to a reverence for the timelessness of the mystery it vests within words.