Liturgical Hermeneutics of Sacred Scripture. By Marco Benini. Reviewed by Fr. Vien V. Nguyen, SCJ. (skip to review)

Theology as an Ecclesial Discipline: Ressourcement and Dialogue. By Archbishop J. Augustine Di Noia, O.P. Reviewed by Rev. Ryan Connors. (skip to review)

Beauty and Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts. By Daniel McInerny. Reviewed by Daniel B. Gallagher. (skip to review)

Ceremonial for Priests. By Msgr. Marc B. Caron. Reviewed by Rev. Lucas LaRoche. (skip to review)

Dominican Brothers: Conversi, Lay, and Cooperator Friars. By Fr. Augustine Thompson, O.P. Reviewed by Aaron Martin. (skip to review)

Liturgical Hermeneutics of Sacred Scripture – Marco Benini

Benini, Marco. Liturgical Hermeneutics of Sacred Scripture. Translated by Brian McNeil. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2024. 379 pages.

Reviewed by Fr. Vien V. Nguyen, SCJ.

The book, translated from German, offers an in-depth investigation of the relationship between liturgy and Sacred Scripture, specifically examining how Scripture is used in the liturgy and how its use influences our interpretation (hermeneutics) of Scripture. As noted succinctly by Marco Benini, “Scripture influences the liturgy and that, on the other hand, the liturgy contributes to the understanding of Scripture” (p. 7). He further asserts that “the two ‘directions’ — from Scripture to liturgy and from liturgy to Scripture — permeate each other” (p. 7). For Benini, a liturgical biblical hermeneutics addresses “the question of how the Bible is received in the celebration of the liturgy and understood by those who take part in worship” (p. 9).

The book, translated from German, offers an in-depth investigation of the relationship between liturgy and Sacred Scripture, specifically examining how Scripture is used in the liturgy and how its use influences our interpretation (hermeneutics) of Scripture. As noted succinctly by Marco Benini, “Scripture influences the liturgy and that, on the other hand, the liturgy contributes to the understanding of Scripture” (p. 7). He further asserts that “the two ‘directions’ — from Scripture to liturgy and from liturgy to Scripture — permeate each other” (p. 7). For Benini, a liturgical biblical hermeneutics addresses “the question of how the Bible is received in the celebration of the liturgy and understood by those who take part in worship” (p. 9).

The investigation is presented in three parts. In Part A, Benini analyzes and compares scriptural readings used in the Western and Eastern liturgical traditions. He focuses on the use of Scripture in various liturgical celebrations (e.g., the Mass, the sacraments, the Liturgy of the Hours). He also discusses references and allusions to Scripture found in prayers, orations, and songs, as well as the connection of Scripture to actions and signs of the liturgy (e.g., the Washing of the Feet on Holy Thursday, the Clothing with the White Baptismal Garment). In Part B, Benini offers a systematic overview of the dimensions of a liturgical hermeneutics of Sacred Scripture, focusing on the various approaches to understanding Scripture that the celebration of the liturgy opens up access to God, the liturgical context as a hermeneutical key, the theological aspects of the liturgical hermeneutics of the Bible, and the reception of Scripture in the celebration of the liturgy. In Part C, the author offers insights and perspectives on the liturgical approach to Scripture.

Benini employs a comparative method to analyze the use of Scripture in the liturgical rites of the West (Roman and Milanese or Ambrosian) and the East (Byzantine). He engages with the magisterium of the Catholic Church (Sacrosanctum Concilium, Verbum Domini, and Dei Verbum) and patristic writers (e.g., Ambrose, Augustine, Origen). Additionally, with the interdisciplinary approach, i.e., liturgy and Scripture, he contributes to the dialogue between the two theological disciplines, biblical studies and liturgical studies, effectively bridging the two fields of scholarship.

Given the plurality of interpretive approaches and methods in contemporary biblical studies that do not pay attention to the liturgy, the liturgical hermeneutics of Sacred Scripture is a welcoming addition, not only in liturgical scholarship but also from the perspective of biblical theology (p. 313). It helps readers understand how Scripture is used in different liturgical contexts and forms and how it is received and understood by those who participate in worship (p. 9). Moreover, liturgy is the celebration, articulation, and actualization of the Church’s life, and Scripture is God’s self-communication to humanity (p. 168). Liturgy draws people into the realms of Scripture (p. 264).

Benini offers several insights regarding the liturgical hermeneutics of Scriptures: 1) In the liturgy, Scripture is not merely a historical document but is the living Word of God — a testimony to God’s salvific action in the present; 2) Scripture in the liturgy functions as a medium through which participants can encounter God in the here and now, with Christ as the protagonist; 3) The liturgy functions as an interpreter of Scripture by means of the order of readings of the Mass, highlighting the intertextual relatedness among the individual texts and the unity of the two Testaments; 4) The liturgy presupposes the unity between Old and New Testaments, with a Christological orientation; 5) A liturgical hermeneutics of Scripture contains both enduring elements and those that are influenced by time; and 6) A liturgical hermeneutics of Scripture contributes to the formation of a Christian identity that is nourished by both Scripture and liturgy (pp. 314-316). For Benini, “a liturgical approach to Scripture deserves a place in the wider academic discussion” (p. 15).

What can readers expect to gain from it? They will find comprehensive explanations of some significant questions, including: “What are the hermeneutical consequences for the understanding of Sacred Scripture when it is employed in the liturgy?” “How does the liturgical celebration influence the interpretation of Scripture or of the specific pericope?” “What theological aspects can be discerned behind the phenomenon of the liturgical reception of Scripture?” “What relation between the Old Testament and New is mediated by the Liturgy?” “What is the reciprocal relationship between Bible and celebration?” “What accents do the liturgical year and the liturgical setting, or the selection and combination of scriptural passages in readings, prayers, and hymns, introduce into the understanding of Scripture and of individual pericopes, and what accents are thereby blurred?” (p. 10).

The book is a valuable resource for readers interested in understanding the use and connection of Scripture and liturgy. It offers a comprehensive study that enhances readers’ understanding and appreciation of pertinent questions regarding Sacred Scripture within the liturgical context. This book is a must-read for liturgists and biblical scholars alike.

Fr. Vien V. Nguyen, SCJ, is a priest and provincial superior of the Priests of the Sacred Heart (Dehonians or SCJs) in the United States. Holding a doctorate in Sacred Scripture from Santa Clara University, Fr. Vien was an assistant professor of Sacred Scripture at Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology in Hales Corners, Wisconsin, before his election to provincial leadership in 2022.

Theology as an Ecclesial Discipline – J. Augustine Di Noia

Di Noia, J. Augustine, OP. Theology as an Ecclesial Discipline: Ressourcement and Dialogue. Edited by James Le Grys. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2024. 343 + ix pages.

Reviewed by Rev. Ryan Connors.

Archbishop J. Augustine Di Noia takes his place as one of the most significant American prelates of the early part of the twenty-first century. His service to the Dominican order, to the bishops of the United States, and to the Holy See merits the gratitude of Catholics in the United States and everywhere. This volume, meticulously edited, brings together the Archbishop’s essays from the last several decades. Scholars and other interested believers will welcome this volume and find in it theological reflection from the heart of the Church.

Archbishop J. Augustine Di Noia takes his place as one of the most significant American prelates of the early part of the twenty-first century. His service to the Dominican order, to the bishops of the United States, and to the Holy See merits the gratitude of Catholics in the United States and everywhere. This volume, meticulously edited, brings together the Archbishop’s essays from the last several decades. Scholars and other interested believers will welcome this volume and find in it theological reflection from the heart of the Church.

The text unfolds in eighteen chapters. Editor James Le Grys brings together largely — but not entirely — previously published essays in a delightful collection. Some of the essays date from Di Noia’s service to the Holy See, first at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (2002–2009, and again, 2013–present), and also at the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (2009–2012).

The book is divided into three sections: one on the nature and mission of Catholic theology, a second offering a corrective to certain modern and postmodern errors through a retrieval of the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, and a third on dialogue, especially related to baptized non-Catholics as well as to non-Christians. In each chapter Archbishop Di Noia shows himself a man of the Church. His thinking eschews a hermeneutic of rupture and calmly demonstrates both a continuity of Catholic teaching through the ages and an openness to all that is true.

In the essay, “Not Born Bad: The Catholic Truth about Original Sin in a Thomistic Perspective,” Di Noia corrects the common misunderstanding that, as a result of original sin, people are “born bad.” Instead, he reminds us that original sin refers in the first place to the loss of original justice. The lack of sanctifying grace and the preternatural gifts constitutes a privation of what was and should be. However, sinful man retains the goods of human nature. Di Noia explains: “Original sin is not an inclination to evil, but a lack of facility in choosing the good. Its character is essentially privative not positive” (252–53).

Another chapter, what began as a 2005 address, “The Dominican Charism in Catholic Higher Education: Providence College on the Eve of Its Second Century,” has borne fruit in recent years. Some two decades ago, Di Noia explained: “I shall argue that among the concrete measures that need to be taken at present should be . . . to strengthen the Dominican identity of the College as the key to securing and fostering its Catholic identity” (105). Indeed, one of the happy fruits of a certain renewal in Catholic higher education in the last two decades has been a strengthened Dominican identity at Providence College. This renewal has come about, not without difficulty, thanks to the commitment of a cadre of both Dominican and lay faculty. A related essay recounts the history of the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, DC. These chapters will be of interest to those who chronicle Catholic higher education, and especially religious formation, in the United States.

In the same vein, the essay, “Taking the Cure at Yale: From Aquinas to Rahner and Back (by Way of Wittgenstein and Barth)” chronicles Di Noia’s own intellectual path during doctoral studies in New Haven. This chapter includes some delightful anecdotes about the influence of his dissertation director, the Lutheran theologian and progenitor of postliberal theology, George Lindbeck (1923–2018).

Some chapters (not yet previously available) of the book under review will be of particular interest to those who follow closely magisterial pronouncements. A 2017 essay on recent magisterial statements on “Catholic theology of religions” as well as a chapter on “Christian universalism” will garner interest especially with those familiar with Di Noia’s previous important contributions to that field of research.

Readers will note with pleasure the Archbishop’s prose. Careful, erudite, and subtle describe these chapters. The cover image of the fifteenth century Gozzoli, The Life of St. Augustine: St. Augustine teaching in Rome, reminds readers of Di Noia’s own ecclesial service. This great theologian was taken up into the service of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishop and later of the Holy See. In this respect, like his religious namesake, Di Noia the theologian has offered himself in service to the Church.

At his episcopal consecration in 2009, Archbishop Di Noia chose as his episcopal motto “In oboedientia Veritatis” — “In obedience to the Truth.” Indeed, these essays demonstrate that Catholic theology unfolds in obedience to the Truth, always as an ecclesial discipline.

Rev. Ryan Connors is a priest of the Diocese of Providence and Rector of the Seminary of Our Lady of Providence (Rhode Island). He is the author of Rethinking Cooperation with Evil: A Virtue-Based Approach (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2024) and co-author with J. Brian Benestad of Church, State, and Society: An Introduction to Catholic Social Doctrine, Second Edition (Washington, DC, The Catholic University of America Press, forthcoming).

Beauty and Imitation – Daniel McInerny

McInerny, Daniel. Beauty and Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts. Elk Grove Village, IL: Word on Fire Academic, 2024. 448 pages.

Reviewed by Daniel B. Gallagher.

When Aristotle described the arts as “mimetic,” he hardly could have imagined the direction academia would take it. Mimesis simply means “imitation,” though not merely in the sense of “copying.” Correctly understood, mimesis has enormous potential to explain what happens in music and painting, let alone in narrative and literary arts such as fiction, poetry, and drama.

When Aristotle described the arts as “mimetic,” he hardly could have imagined the direction academia would take it. Mimesis simply means “imitation,” though not merely in the sense of “copying.” Correctly understood, mimesis has enormous potential to explain what happens in music and painting, let alone in narrative and literary arts such as fiction, poetry, and drama.

McInerny does a superb job of unpacking mimesis. Without getting caught up in academic jargon and controversy, he helps the reader to reason through what really happens in art. Mimesis consists in the “re-presentation of an object in the alien matter of a particular artistic medium for the sake of making the object delightfully intelligible to an audience” (xiv). That kind of down-to-earth, accessible prose allows McInerny to handle an otherwise maddeningly obscure topic.

The object of art, Aristotle explains, is “human beings in action.” The key to understanding what Aristotle means is to first acknowledge that human beings undertake any action for the sake of eudaimonia (“blessedness” or “happiness”). If this is the case, and if all mimetic arts have some kind of narrative dimension, then they all present some kind of moral argument. McInerny is well aware how bold this claim is, but he doesn’t back down from brilliantly defending it. His defense sets the stage for the clearest explanation I have yet read of what the “Catholic imagination” is, another term that has been spaghettified, even by well-intentioned authors. The Catholic imagination describes an artist who “takes in the world through images” formed by Catholic belief (xvi). McInerny’s Aristotelian-Thomistic approach to mimetic art requires, therefore, a “theological horizon” (xiv), but one he lucidly illustrates with the help of Willa Cather, Flannery O’Connor, Fyodor Dostoevsky, William Shakespeare, Dante Alighieri, and others. In fact, McInerny’s constant use of literary texts allows us to read several perennial works in a new light or encounter them for the first time. More importantly, he interweaves these primary works into his own discussion rather than arrange them in a sort of survey, which is precisely the weakness of many modern anthologies on “aesthetics.”

The argument at the core of the book is that “the function of art is to move its audience by beauty’s peculiarly cognitive or intelligible delight and, in so doing, incline the sensible and rational appetite of its audience to moral transformation” (xvii). To explain this, McInerny discusses the cognitive or intellectual aspect of the experience of art, as well as the effect beautiful art has upon our sensible and rational appetites.

If imitation is not primarily about copying or resemblance, what is it about? McInerny asserts that it is about the “re-presentation of form,” by which he means that the artist, rather than slavishly copying his subject, re-presents it for the audience’s delight, well aware that the audience takes it as a “picture” rather than as a deceptive copy of the original. Cézanne, for example, does not try to copy the fruit or even its appearance in his still lifes. Rather, he “self-consciously abandons traditional rules of perspective that would allow his paintings to closely mimic the three-dimensionality of nature,” knowing that we should “attend” to the way in which he “uses color and design in his still lifes, quite apart from what his still lifes tell me about the human habitat” (18).

Perhaps the locus of mimesis audiences have the most difficulty accepting as “imitation” is story-telling, since, on face value, much story-telling seems to want to embellish or even fabricate reality. Yet there is a universal way of defining story-telling that greatly aids our understanding of its essence. According to McInerny, a story is (1) “an ordered sequence of events with a beginning, middle, and end that pictures the human pursuit of some goal or good”; (2) “in this pursuit, the protagonist encounters conflict keeping him from the goal, conflict that the protagonist resolves or fails to resolve by his own choices, not by chance”; (3) “these choices ultimately reverse the protagonist’s fortunes in a way that is both probable and marvelous and so offer the reader or audience an understanding of the meaning of the protagonist’s adventure”; (4) “an understanding that manifests the adequacy or inadequacy of the protagonist’s purposes to the human end” (53).

The marvelous art of storytelling, therefore, involves an interplay of purpose and end: i.e., the intentions characters have when they act and the very reason(s) for which they act in the first place. Drama fills the space between their intentions and their ultimate end or telos (i.e., happiness) in a way that the audience cannot help but evaluate or judge the extent to which intentions accord or fail to accord with ends. “Stories show us their moral truths by way of dramatization,” McInerny writes. “They dramatize a debate between the habits and attitudes of the protagonist and the counter-habits and counter-attitudes or even just the counter-energies of whatever force of antagonism the protagonist faces” (92).

I cannot overstate how helpful this book is in clarifying the end and nature of art. The principles upon which McInerny discusses select literary works can easily be applied to biblical narratives. With due regard for the spiritual senses of scripture, the mimetic power of Old Testament stories and New Testament parables come to life if we approach them as mimetic in their own unique way. Preachers may even understand better why they use stories themselves by gaining a greater insight into why audiences take delight in mimesis and arrive at moral insights and transformations that cannot be achieved otherwise.

If one wants to read only one accessible, coherent book on art theory, McInerny’s is it.

Daniel B. Gallagher is a Lecturer in Literature and Philosophy at Ralston College.

Ceremonial for Priests – Msgr. Marc B. Caron

Caron, Msgr. Marc B. Ceremonial for Priests. Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2023. 450 pages.

Reviewed by Rev. Lucas LaRoche.

The Church in the United States has been amid a Eucharistic revival for two years now, with still more than six months to go. The fruits of this revival have already been palpable. The revival itself has focused on Eucharistic Adoration; this is a noble cause and one worth encouraging. Nonetheless, we ought to remember that for many Catholics (and, indeed, non-Catholic inquirers and visitors at parishes) the primary encounter with the person of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist happens not in Eucharistic Adoration, but during the celebration of the Mass, be it on weekdays, Sundays, or Holy Days in parishes, or occasional Masses like weddings and funerals. To improve reverence toward the Eucharist and belief in the Real Presence, priests, then, ought not to just focus on preaching about and adding times for Eucharistic Adoration, but also to seriously look at how they celebrate Mass in their parishes and chaplaincies.

The Church in the United States has been amid a Eucharistic revival for two years now, with still more than six months to go. The fruits of this revival have already been palpable. The revival itself has focused on Eucharistic Adoration; this is a noble cause and one worth encouraging. Nonetheless, we ought to remember that for many Catholics (and, indeed, non-Catholic inquirers and visitors at parishes) the primary encounter with the person of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist happens not in Eucharistic Adoration, but during the celebration of the Mass, be it on weekdays, Sundays, or Holy Days in parishes, or occasional Masses like weddings and funerals. To improve reverence toward the Eucharist and belief in the Real Presence, priests, then, ought not to just focus on preaching about and adding times for Eucharistic Adoration, but also to seriously look at how they celebrate Mass in their parishes and chaplaincies.

To this effect, Monsignor Marc Caron’s book, Ceremonial for Priests, is invaluable. The book is the most exhaustive compilation of the contemporary norms and rubrics governing the celebration of the Mass, beginning with basic gestures ranging to comprehensive treatments of the ceremonies of the Triduum. Additionally, he treats occasional ceremonies, as well as adaptations for smaller churches, and for episcopal ceremonies in parish settings. The overall style functions, in some way, as a successor to Bishop Peter Elliot’s Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite and the related works by the same author, but Caron manages a wider-ranging work with a more cohesive rationale.

Whereas the ars celebrandi of many individual priests are more formed by a variety of opinions (varying in quality), one of the author’s greatest contributions is his thorough footnotes throughout the work. He provides references from all authoritative liturgical texts in currently in use. Additionally, Caron’s use of several commentaries, especially French commentaries unavailable in English, provides a more exhaustive foundation for his description of the ceremonies than available in other texts.

Most valuably, Caron’s work provides what may serve as a way forward for improving the quality of liturgies in most parishes. While many commentators had stated that, in current liturgical debates, the “reform of the reform” camp is dead, the publication of Traditionis custodes has dealt a blow (or at least a delay) for those who have championed the reintroduction of the Roman Missal of 1962. Nonetheless, growing numbers of clergy and the lay faithful are calling for an improvement in the quality of the liturgy at their local parish.

Caron admits that the current liturgy may suffer from as wide a variety of artes celebrandi as there are priestly celebrants. As a result, Caron begins with the admission that many priests incorporate and combine many sources in how they celebrate Mass, including their own liturgical formation, improvisation, and occasional (often uncritical) loans from other liturgical traditions. Caron proposes a remedy to the overabundance of styles through his reading of GIRM no. 42, which states that “the traditional practice of the Roman Rite” should serve as an interpretive key, in combination with the General Instruction, in understanding how the priest ought to celebrate the liturgy. Caron’s work provides a schema, through his combination of the current authoritative texts and his knowledge of the historical Roman Rite, by which he suggests a way in which one may celebrate the post-Conciliar liturgy in an authentic, dignified manner.

The result is, in some ways, a return to idea of the reform of the reform, but one more critical and better-researched than many of the sources which populated that camp before its proponents abandoned it a decade ago. Caron’s book provides a fresh breath into this camp: one that the clergy ought to revisit, if the Eucharistic Revival is to bear lasting fruits in this country. Pastors and chaplains of any age who are willing to take a serious look at how they celebrate Mass and recognize that their own inculcation of the spirit of the Liturgy plays the largest role in how most parishioners experience the Eucharist. Additionally, seminarians may find the book particularly helpful as they prepare to celebrate the liturgy in parish settings.

While the intended audience of the book is admittedly smaller than many publications, if contemporary clergy take the book seriously, its publication may prove to be a major step forward in the liturgical reform that has followed the Council and a definitive step towards the “mutual enrichment” of (what sources previously referred to as) the two “forms” of the liturgy that the late Pope Benedict XVI spoke of.

Rev. Lucas LaRoche is a priest of the Diocese of Worcester. He received an S.T.L. in Patristic Theology and the History of Theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. He currently serves as administrator of Sacred Heart Parish in Webster (Massachusetts), associate archivist of the Diocese of Worcester, and adjunct lecturer in Theology and Pastoral Ministry at Anna Maria College.

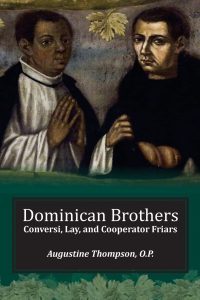

Dominican Brothers – Fr. Augustine Thompson, O.P.

Thompson, O.P., Fr. Augustine. Dominican Brothers: Conversi, Lay, and Cooperator Friars. Chicago, IL: New Priory Press, 2017. 286 pages.

Reviewed by Aaron Martin.

When reading or writing about history, one often thinks of the alleged debate between historians about whether Herodotus or Thucydides was better. Both men recorded and retold stories of important events, but the styles were different. This is an oversimplification, but one could say that Thucydides focused on the major events and the broad arc of history while Herodotus focused on the individuals who participated in and shaped the events. Thucydides may talk about a group of important men; Herodotus would give you their names and explain a bit about them as people. Fr. Augustine Thompson is firmly in the Herodotus camp. And it’s fascinating.

When reading or writing about history, one often thinks of the alleged debate between historians about whether Herodotus or Thucydides was better. Both men recorded and retold stories of important events, but the styles were different. This is an oversimplification, but one could say that Thucydides focused on the major events and the broad arc of history while Herodotus focused on the individuals who participated in and shaped the events. Thucydides may talk about a group of important men; Herodotus would give you their names and explain a bit about them as people. Fr. Augustine Thompson is firmly in the Herodotus camp. And it’s fascinating.

It is rare that one hears of a man entering a religious order today with the explicit intention to be a brother. The vast majority of men entering feel called to be priests and the formation programs in religious orders are geared toward ordination to the priesthood. So Fr. Thompson’s book is a welcome explanation of the history behind and the key role played by lay Dominican brothers in the last 800 years.

Telling the history of these brothers — Marcos de Mena, Pedro de la Magdalena, Jacques Grou, and others — is also a useful way of telling the history of the Church and its spread to all parts of the world. The brothers taught and evangelized throughout the world. Even though they did not have the faculties to preach in public or in their religious houses, they were still preachers in their actions and their lives of prayer and penance.

Early “conversi,” those who had converted from secular life to religious life, made up the initial group of brothers. The conversi dedicated themselves to a life of penance and performed work on behalf of the community. Early in the Order’s existence, conversi made up approximately 20% of each religious house. They were integral to the inner workings of each house and, over time, began to extend their services outside the houses as well.

One such story is of Marcos de Mena, a Spanish brother “born in Villar del Pedro near Talavera, Spain.” (142) Headed for Mexico, he was shipwrecked with others near the Mississippi River. “Almost immediately, the stranded party was attacked by Indians.” (142) Then, after Brother Marcos escaped, he and two companions caught up with the rest of their party. “After twenty exhausting days on foot, they reached a river, probably the Trinity River in what is today eastern Texas.” (142) And “[w]hile camped on the banks of the river, they were again attacked by Indians.” (142) This time he escaped, but he was found by the Indians later and “took seven arrows, one in the face, and fell to the ground.” (143) His brothers buried him in the sand.

But, miraculously, Brother Marcos survived. “Marcos dug himself out” of his grave. “He found himself bloody, naked, and riddled with arrows.” (143) “In an unbelievable trek, not even considering his physical condition, Brother Marcos made his way overland, some seven hundred miles, to the Pánuco River in central Mexico.” (143) After collapsing on the riverbank and being transported another twenty miles by caring Indians, Marcos was able to return to Mexico City where he “underwent painful surgery to remove the arrows. The whole adventure had taken between twelve and eighteen months.” (143)

These men suffered tremendously for the sake of the Gospel. They devoted all their energies to the people served by their communities and some, like Brother Marcos, did so heroically.

But over time, the role of the brother has changed quite a bit. After the initial conversi — who were mainly focused inwardly on the religious house — many brothers were sent to evangelize in the missions where there were fewer priests and where they could take on a more prominent role. Over time, due to the requirements that priests have certain academic training (including Latin), ranks of brothers were often made up of those who did not have much formal education, or who at least lacked the more classical education required of a candidate for Holy Orders.

That idea that brothers were those who had less education stuck until the requirements for priests were lessened after the World Wars and the Second Vatican Council. “During the vocations boom [in the 1950s], the spread of mass education, as well as lesser standards for clerical Latinity, meant that the percentage who sought a priestly vocation could and did go up. And this meant the percentage of brother vocations went down.” (203)

Today, cooperator brothers play a vital role in Dominican houses and provinces. And there are signs that vocations for brothers are increasing. Fr. Thompson notes that even with a significant increase in vocations, the numbers are far below a replacement rate given the age of the brothers today. And it is slow growth. Although there are signs of life, as of the end of “2015, there were, worldwide, 21 brothers in formation, of whom all but one were in Vietnam, Poland, or English-speaking entities.” (267)

Fr. Thompson seems hopeful about new vocations as cooperator brothers. It may not be a new springtime, but there are many signs of new life. Despite the Dominican Order’s clerical focus, many young men today feel the call to serve the Lord as brothers in whatever form that takes. And their decision to become brothers rather than priests in a primarily clerical order is notable. These contemporary brothers are following upon the great example of so many brothers before them. The brothers Fr. Thompson profiles in the book give a human face to many historical events and time periods. They help enliven Church history, and it is encouraging to see a new generation of brothers enlivening the Church in our own age.

Aaron Martin, JD, PhL, and his wife live in Phoenix, AZ with their four children. Aaron owns his own law practice and serves in various ways in the Diocese of Phoenix. He also is a member of the USCCB’s National Review Board. He writes at martinlawandmediation.substack.com.

Recent Comments