A Catholic writer is a Catholic writing for other Catholics. … On another level, a Catholic writer is a Catholic writing for a wider audience, but still drawing upon the biblical, classical, and patristic heritage of Christendom.

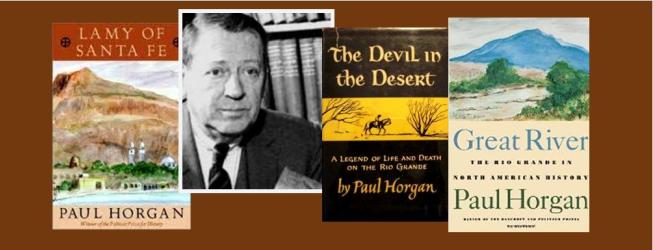

Soon twenty years will have passed since the death of Paul Horgan. In his heyday, Horgan (1903-1995) was an acclaimed historian and novelist, receiving the Bancroft and Pulitzer prizes (the latter twice), as well as several fellowships, medals, and honorary degrees. In 1957, Pope Pius XII made him a Knight of Saint Gregory, acknowledging Horgan’s contributions to Catholic literature; and in 1960, Horgan served as president of the American Catholic Historical Association. Now, however, Horgan seems to be known only to a few aficionados; most of his nearly forty books, once bestsellers, are out of print. This essay seeks to dust off Horgan’s name by focusing on his depiction of Catholic priests, in particular in two short stories. Since Horgan wrote history as well as fiction, this study will close by considering priests in some of his historical works.

Perhaps, Horgan’s disappearance from public, if not critical, appreciation derives from his identification as a regional, and a Catholic, author. He disliked such categorization, but Paul George Vincent O’Shaughnessy Horgan was Catholic and wrote mainly about one geographical area. As a regional writer, he ranks with his contemporaries Louis Auchincloss (1917-2010), Conrad Richter (1890-1968), and Eudora Welty (1909-2001). As does any serious writer, each had a variety of interests, but these three authors are best known for writing about their home regions. Auchincloss in his essays and stories brought to life the upper-crust society of New York City, and Richter and Welty conveyed the small-town and rural worlds of Pennsylvania and Mississippi, respectively. Just so, Horgan captured the stark lives of the settlers and natives of New Mexico. Nevertheless, despite their excellent prose and profound understanding of human nature, these authors all seem to fall into the second rank; somehow, Horgan has not survived in literary memory even to stand alongside another contemporary Catholic, regional author, Flannery O’Connor. A British literary critic, Sir Frank Kermode, surmised that although Horgan “wrote with care and precision,” he “was not much interested in the kind of formal experiment that helped elevate [William] Faulkner from the category of regional novelist.” 1

So, just as one must haunt used bookshops for copies of books by once ubiquitous authors such as John O’Hara and John P. Marquand, so, too, must one mount a bibliophile’s safari and hunt high and low for editions of works by Paul Horgan. Here we will look at two of Horgan’s tales that were once readily accessible but are now unfortunately quite obscure. “The Devil in the Desert” first appeared in 1950 in The Saturday Evening Post, and was then published as a slender hardback book with the same title (1952), and then along with two other stories in an Image Books paperback edition called Humble Powers (1955). That last volume also includes the other story to be considered here, “The Soldier Who Had No Gun,” which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1951, and reappeared in Humble Powers as “To the Castle.” Both stories feature Catholic priests, one a missionary along the Rio Grande, the other a chaplain during the Second World War.

Fr. Louis Bellefontaine, the main character in “The Devil in the Desert,” is from France and has been in the mission field for more than thirty years. 2 The story takes place in the late nineteenth century on the border between Texas and Mexico, where Fr. Louis, despite age and infirmity, insists on making one more sojourn into the desert to offer Mass for the Texas Mexicans. Once among them, he would also baptize, confirm, hear confessions, and bless marriages. He looks upon the poor families in the parched land by the mighty river as his special flock. For all his compassion and devotion, Fr. Louis is a proud and peevish man, with an ongoing struggle “to control a capacity for anger which could flare as quickly and as madly as a cat’s.” He is aware of this weakness and dislikes it; after each burst of temper, he does penance and prays “to be forgiven and to be granted strength once more to conquer himself.”

On this particular journey, Fr. Louis encounters a demon, something common to the Desert Fathers of the third and fourth centuries. The priest and the devil spar with deadly courtesy. Their battle of wits hinges upon the meaning of life and death, good and evil. Fr. Louis acknowledges that he is “an old man full of pride and sin and vanity and all the rest of it,” and yet, he declares, “I, and all creatures, draw our share of time in this life from God, our Father in heaven.” He is amazed at the crystal clarity with which he can array his argument, for he is sharply aware of his increasing fatigue and besetting vices. “Horgan’s is a powerful moral imagination,” observed Ralph McInerny, “and his characters disturb by their simple verisimilitude and what they tell us about ourselves.” 3 Fr. Louis of the desert, prickly and stubborn, is nevertheless deemed worthy to contend with the dark limits of this world; if we are honest with ourselves, we must admit that as fallen-but-redeemed creatures, we are also as unheroic and yet can be as noble.

The chaplain, never named, in “The Soldier Who Had No Gun” is from New Mexico but had studied theology in Rome. 4 His ancestry is Mexican, and the lieutenant narrating the story guesses that the chaplain, a major, is “probably a Franciscan.” The chaplain is a short, wiry man with short, black hair and bright, black eyes. The setting of the story is in March, 1944, and the American advance on Rome; an Army platoon must take a medieval castle near Vitri held by German troops. The occupied castle is blocking the American progress north and cannot be bypassed.

When the chaplain drives up in his jeep, and meets up with the platoon, the soldiers are exhausted and scared, and their lieutenant is not certain they will obey orders to move on the castle. The chaplain subtly addresses their weakening morale by building a small fire and asking them to explain to him a newfangled invention he has heard about, something called “television.” The primeval focus of people telling stories around the fire contrasts with what will soon become the modern replacement, a flickering box telling stories to people. The diversion of attention from themselves, and their fears, to teaching something to an unwelcome, otherworldly little man has the desired effect. The chaplain, a quietly wily man of unassuming grit, then joins the newly emboldened men on their mission to capture the old castle—hence the story’s title, the chaplain being the soldier without a gun.

What George Weigel said of Horgan’s novel, A Distant Trumpet (1960), that it presents a “compelling portrait of manly virtue, marriage, and mature patriotism,” 5 pertains to all his fiction. Even when his main subject is a Catholic priest, one learns something about the commitment and sacrifice one may first associate with married life. Without divulging the end of the story, it can be said that Horgan’s World War II chaplain personifies manly virtue and becomes for that platoon a Christ figure. Something of Horgan’s own faith and patriotism may be seen in a statement made by the narrator: “I shall always see the rosy clay of the Rio Grande and the vista of the buildings of Rome as the same color.”

The priests in these two stories have in common courage that does not call attention to itself, what another of Horgan’s fictional priests, Fr. Koch (but pronounced Coach), calls “the heart of a soldier, and the will of an athlete, who thinks he could serve Our Lord however hard it might be.” 6 They also have in common the spiritual and cultural inheritance of Western Christianity. Both Fr. Louis and the Army chaplain, sixty or seventy years later, experienced and shared the continuity of the Christian centuries. For all their foibles and quirks, Horgan’s priests are missionaries, emissaries, of two messages, bringing not only the Gospel and the sacraments to the poor, but also bringing what John Lukacs calls “the remembered past” of the Old World to the New.

The chaplain from New Mexico stirred in the young lieutenant a longing to see Rome, and when in early June, 1944, the platoon approaches the Eternal City, the narrator describes the scene. “I could see the dome of St. Peter’s,” he recalls, “like a soft cloud in the filtering dust above the city.” It conjured an optical illusion. “It looked immense from a distance and seemed to retain its size without increasing as we neared it, though all other buildings about it grew with diminished distance.” It was where the chaplain had studied, at the Franciscan college, taking memories of Rome back to the desert of New Mexico. The chaplain tells the lieutenant that he wants to return to Rome to see the places in St. Peter’s where he had prayed, saying that “probably the most enduring of all things is an act of the spirit.”

Likewise, Fr. Louis brought with him, from France to America, the legacy of Catholic civilization. He would regale his Mexican flock with newspaper reports and personal recollections of “the cool green fields, the ancient stone farmhouses, the lanes of poplar trees, the clear rivers; or the proud old towns, or the glorious towering cathedrals.” Such evocative scenes the indigenous peasants of southwest Texas could not quite imagine. Fr. Louis also has an idea about the enduring qualities of life and goodness. He tells the devil, “the fact is that evil must be done to death, over and over again, with every act of life.” Thus, “only by acts of growth can more life be made, and if all evil, all acts of death, were ended once and for all, there would be nothing left for the soul to triumph over in repeated acts of growth.”

Although this essay has chosen to focus, first, on two fictional priests depicted by Paul Horgan, a well-rounded view must consider some priests in Horgan’s historical writing. He wrote in the grand tradition of narrative history, thus standing in a long and distinguished line, beginning in English, with Edward Gibbon. Like Gibbon, Horgan was not an academic historian, but unlike Gibbon, his histories are not studded with superscript numerals, and thus buttressed by ponderous footnotes. Instead, Horgan’s research is indicated by his extensive bibliographies, citing sources in four languages. In addition, Horgan avoids Gibbon’s sharp irony.

Over the years, Horgan worked as a librarian at the New Mexico Military Institute, and taught at Yale and Wesleyan universities in Connecticut. He held these posts without any of the usual credentials. Horgan’s formal education was from only one year at the Eastman School of Music, in Rochester, New York. Yet, his eye for historical scenes, and the flaws and merits of human character, were informed by his pitch-perfect ear for themes and movements in music. When looking for help while practicing the craft of writing, one can learn a lot from the spare, yet elegant, prose of Paul Horgan. “His portraits of the principals,” wrote David McCullough of Horgan’s epic history, Great River, “are invariably deft, often spectacular, in what they convey with a minimum of strokes.” 7 Here should be noted the not surprising fact that Horgan was also a skilled watercolorist and pen-and-ink artist.

In Conquistadors in North American History (1963), Horgan addressed the religious basis for the Spanish conquest of Mexico. “Jesus Christ instituted the papacy in the person of St. Peter and his successors,” Horgan explained, “through whom the Catholic kings of Spain renewed the authority of the crown with the death of each king, and the coronation of each heir to the throne.” He added: “It was an authority unquestioned, because to any Christian it was unquestionable.” 8 One need not agree with such a worldview, but the historian must first understand it before trying to reassemble the often brutal facts that flow from it. It is a perspective alien to the American mind, where authority lies in each individual. But, Horgan had grappled with it, and could put it in plain terms for his readers. The blood-soaked pages of the Spanish conquest’s chronicle could seem abhorrent to anyone with a trace of Christian sensibility. “To the priest,” Horgan concluded, “the conquest promised that throng of souls, whose salvation in Christ, he was born to achieve.” 9

In Great River (1955), and in The Centuries of Santa Fe (1956), Horgan related the role of Franciscan friars from Spain in the European settling of the desert Southwest. Horgan admired those pioneers, men of strong faith and hard work, simple, in the best sense. In time, their missionary foundations were built upon by diocesan priests from France. Here was the historical setting for the fictional Fr. Louis Bellefontaine, as well as for the factual Archbishop Jean Baptiste Lamy (1814-1888), subject of Willa Cather’s novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927). In 1957, in American Heritage magazine, Horgan published an article on Lamy; in 1975, he completed a five-hundred-page book about him, Lamy of Santa Fe. If not exactly his life’s work, it was certainly the work of decades, as well as a labor of love.

In Part 3, Chapter 3, of The Seven Storey Mountain, Thomas Merton says that “it is a wonderful experience to discover a new saint.” Horgan’s monumental biography of Lamy is an act of reverence, almost a work of hagiography. Saints, though, are sinners who always repent and never quit searching for God. To underscore his sustained implication of Lamy’s sanctity, Horgan quoted John Henry Newman’s description of St. John Chrysostom, applying it to Lamy. It is a lengthy assessment, Newman’s Victorian prose having a leisured pace, among which are these words: “I speak of the discriminating affectionateness with which he accepts every one for what is personal in him, and unlike others.” 10 It is a goal for all Christians, especially all priests.

One cannot come away from Horgan’s studies of Lamy without a sense of awe at such a brave and holy man. Yet, Horgan’s clear eye never wavers from the fact that Lamy was a man, marked by weaknesses, as well as strengths. A reticent, formal man, he seems to have come across as rather dull: “In repose, Lamy was like a medieval sculpture of a bishop, whose eyes saw beyond time.” 11 Quiet men, however, can get on as well as jolly extroverts. Lamy was well-received by the local Jewish community, and by Protestants, such as Gen. Lew Wallace, governor of New Mexico, and author of the novel, Ben-Hur.

Of course, when a Catholic writes about priests and saints, he becomes liable to being labeled, or dismissed, by critics as merely a “Catholic” writer. As noted at the beginning of this essay, Horgan saw his writing in broader terms. He did not appreciate being pigeon-holed or written off, as a religious or regional writer. Since most of his writing, whether fiction or nonfiction, was set in New Mexico, it is hard not to place Horgan as a regional author. Since he was a practicing Catholic, and often wrote about Catholic themes, both in fiction and in nonfiction, it is worth considering what makes a Catholic writer.

On one level, a Catholic writer is a Catholic writing for other Catholics. Among novelists, Louis de Wohl (1903-1961) comes to mind: his pious, page-turning novels about popular saints are meant to entertain and edify faithful Catholics. On another level, a Catholic writer is a Catholic writing for a wider audience, but still drawing upon the biblical, classical, and patristic heritage of Christendom. An example of this approach is Graham Greene (1904-1991), whose exquisitely crafted novels often explored ethical problems relevant to Catholics and others, and whose two novels about priests—The Power and the Glory (1940) and Monsignor Quixote (1982)—showed the inner struggles of priests conflicted by secular, 20th century society.

If we accept this outline, Paul Horgan would also appear under the second designation. In either case, a Catholic writer must let the reader see how the character—either fictional or historical—grew under his or her own experience of the cross of Christ. For the Catholic writer must have an awareness of, and gift for, portraying a fellow Christian being part of the body of Christ. (This principle of charity is true, also, for Protestant writers, such as C. S. Lewis, and Jan Karon.) The writer’s presentation may be direct and didactic, or oblique and ambiguous, but, assuming the protagonists are Christians, the personal adventure—in the novel, or history, or biography—must partake of the saving work of the Cross. Whether Paul Horgan was writing about Fr. Louis Bellefontaine, or Archbishop Jean Baptiste Lamy, he was showing the reader—even a possibly nonbelieving subscriber to The Saturday Evening Post or American Heritage—the way in which those figures tried, and tried again, to follow Christ, bringing Christ into the lives of others.

- Frank Kermode, “Discreet Southwestern Charm,” The Guardian (20 March, 1995), p. T-12.; cf. Richard Bernstein, “Paul Horgan, 91, Historian and Novelist of the Southwest,” The New York Times (9 March, 1995), p. B-13: Critics who admired Horgan’s writing believed he was excluded from the front rank because “his writing was too traditional and old-fashioned to compete with the likes of Faulkner or Hemingway.” ↩

- Paul Horgan, “The Devil in the Desert,” The Saturday Evening Post (6 May, 1950), pp. 24-25 and 86-88 , 90, 93-95, 97-98, 101-103. All quotations are from this version of the story. ↩

- Ralph McInerny, “Paul Horgan: Literary Master of the Southwest,” The National Catholic Register (22 January, 1995), p. 10. ↩

- Paul Horgan, “The Soldier Who Had No Gun,” The Saturday Evening Post (13 October, 1951), pp. 22-23, 140, 142, 145, 147-150, 154, 156-163. All quotations are from this version of the story. ↩

- George Weigel, “What to Give a First Things Reader,” First Things, 188 (December, 2008), p. 17. In 2006 Weigel wrote the foreword to a new edition of Horgan’s novel of 1964, Things As They Are. ↩

- Paul Horgan, Things As They Are (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Co., 1964), p. 167. ↩

- David McCullough, “Historian, Novelist, and Much, Much More,” The New York Times Book Review (8 April, 1984), p. 3; cf. John Lukacs, “Last of a Breed,” National Review (25 November, 1988), p. 48: “Horgan’s vision is a triumph of discernment.” ↩

- Paul Horgan, Conquistadors in North American History (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Co., 1963), p. 112. ↩

- Ibid., p. 288. ↩

- Paul Horgan, Lamy of Santa Fe: His Life and Times (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1975), p. 440; cf. Paul Horgan, “Churchman of the Desert,” American Heritage, 8 (October, 1957), pp. 30-35 and 99-101. ↩

- Horgan, Lamy of Sante Fe, p. 416. For the history informing Cather’s novel, see Maria Stella Ceplecha, “Willa Cather’s Archbishop,” Crisis magazine, 19 (March, 2001), pp. 24-29. ↩

Thank you, Brother Bruno, for this wonderful introduction to Paul Horgan’s work!

As one of the readers whose copies of Paul Horgan’s works virtually all have come from the used bookshops Brother Bruno refers to, I think it is wonderful to see Paul Horgan receiving after his death greater recognition. He is a very, very underrated writer. I’ve read To the Castle — the story originally published as The Soldier Who Had No Gun – more than five times now and can honestly say that each time I’ve seen things there I’d missed before. Regional writer or not, Horgan is a great writer.

THank you BrotherBruno for reminding us about Horgan who with his traditional manner of writing gave accuracy in his works. As regards the stories of priests there is a biography ” Parish Priest ” by Douglas Brinkley about Venerable Father Michael McGivney the founder of the Knights of Columbus of which I am seeking writers for a full length screen play Martin Drew Dallas