I would like to propose what I believe is the solution to a major source of misunderstanding between Catholics and Protestants on the one hand, and theologians and exegetes on the other.

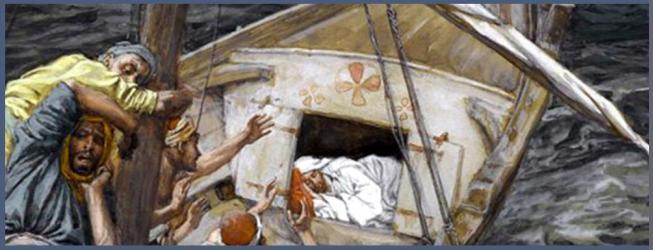

Christ Sleeping Through the Storm at Sea by Tissot

The three virtues of faith, hope, and charity constitute the core of the human response to the Incarnation. No one had ever brought them together before St. Paul made the famous declaration: “Faith, hope, love remain, these three. But the greatest of these is love” (1 Cor 13:13). Ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and Cicero had drawn up portraits of the virtuous man, but never even thought of including anything comparable to these three elements, which are distinctively characteristic of the Christian life. Faith is the fundamental act by which we recognize Jesus as the Christ or Messiah. Hope is our reliance on his saving power. The love of charity is at one and the same time our response to his love, which brought him to us, and our way of communicating his love to our brothers and sisters.

The third member of this triad, which St. Paul calls agape, is translated into English sometimes as love and sometimes as charity. There are advantages and disadvantages in both of these renderings. Here, it is enough to note that what our human language is seeking to express is undoubtedly a form of love, but one that needs to be distinguished from ordinary human love. A more difficult problem, which I wish to focus on here, has to do with the place of hope in this triad. Jesus speaks often of faith (“Your faith has saved you. . .”), and very emphatically about love (“. . . the first and the greatest commandment”), but never singles out hope. At first glance, it might seem as though hope were an addition made by St. Paul.

This matter is closely bound up with one of the famous problems about the nature of faith. In classical Catholic theology, faith has been understood as belief: an intellectual recognition that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, with all that that entails. Since the Reformation, however, Protestant scholars have tended to insist that faith is not merely an intellectual belief, but has much more the character of trust or reliance. Modern critical scholarship has led many Catholic exegetes to side with the Protestants on this point, leaving a few antiquated Thomists to defend the classical concept of faith as intellectual assent.

The two problems just indicated are closely linked; in fact, I believe that one is the solution to the other. Here, I would like to propose what I believe is the solution to a major source of misunderstanding between Catholics and Protestants on the one hand, and theologians and exegetes on the other. 1 To put the matter briefly and schematically, the language of St. Paul is explicating what is implied in that of Jesus. When the Lord summons people to have faith in him, he is calling for them to believe that he is the Messiah. St. John’s Gospel was written, “. . . that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through this belief you may have life in his name” (Jn 20:31).

However, believing that Jesus is the Christ, or Messiah, naturally leads people to trust in him as Savior. Those who regard him as the Messiah, and Son of God, rely on him to deliver them. Thus, when Jesus said to the synagogue ruler, “Don’t be afraid; just have faith” (Mk 5:36), the faith called for was obviously not just an intellectual recognition of his Messianic status, but trust in, and reliance on, his saving power. Likewise, when Jesus reprimanded the disciples for their terror over the storm on the lake, “Why are you terrified? Do you not yet have faith?” (Mk 4:40), he wasn’t referring directly to what they believed about him with their minds, but to their failure to trust in his help. This explains why the first edition of the New American Bible went so far as to replace the term faith with trust in many texts. (Fortunately, the revised edition has restored the term faith, which has a richness of connotation lacking from the term trust.)

Much fruitless squabbling could be avoided if we were to recognize that the real issue here is not between two possible translations of the Greek word, pistis, but between two levels of language: popular and theological. Jesus and his disciples spoke, not in the idiom of theologians, but in that of the people, in which things that usually go together are spoken of together. The faith that Jesus asked for meant, basically, the recognition of him as one sent by God (and ultimately as the Messiah and Son of God). However, it likewise connoted trust in his saving power, and the latter was often the point at issue, as when the disciples, who had just proclaimed him to be the Messiah, were unable to cast out a demon because of their “little faith” (Mt 17:20); or when Peter, stepping out upon the sea of Galilee, lost heart at the sight of the wind and the waves (Mt 14:22-33).

Theologians, however, have to analyze, and distinguish precisely, between attitudes that may be closely bound up together in human psychology. They need to differentiate between the intellectual recognition, which is called belief, and the consequent volitional reliance on Jesus’ saving power, which can be called trust. It was St. Paul himself who set them on this track by distinguishing between faith and hope. Paul was hardly a theoretician; much less was he concerned about niceties of language. But, a man of deep spiritual experience, he sensed that there is a difference, not only theoretical, but practical, between believing with the intellect, and experiencing the confidence which should normally rise out of that belief. The latter he called hope.

Note also that trust and hope designate substantially the same attitude, but from different perspectives. Both refer to the confidence of someone who relies on Christ to bring him salvation; however, trust focuses on his attitude towards Christ, and hope on anticipation of the salvation to come. A Christian trusts in Christ, and on that basis, hopes for salvation; his trust, in turn, is based on the belief that Jesus is indeed the Savior. Thus, there is no conflict between the bipolarity of Jesus’ teaching about faith and love, and the tripolarity of St. Paul’s “faith, hope, and love.” The hope which St. Paul designates explicitly is implied in the faith for which Jesus calls. Consequently, the question about whether New Testament faith should be interpreted as belief or trust is not an issue that needs to divide Catholics from Protestants, nor theologians from exegetes.

The question is rather whether we choose to use a refined psychological language that distinguishes the volitional attitude of hope from the intellectual belief that underlies it, or whether we prefer a holistic language that keeps them together, as they normally are in real life. But, there is no doctrinal or ideological conflict between the holistic language that keeps them together, and the theoretical language that distinguishes them; there is simply a choice between two different linguistic instruments, each suited for a different work.

Thus, when St. Thomas Aquinas treats faith as an intellectual assent, he does not mean that this accounts adequately for the way the word is used in the Gospels; he is simply delineating one of the factors, one may even say the fundamental and principal factor, in that religious attitude which the Scriptures designate as faith. And when the exegete insists that pistis in the New Testament often focuses more on trust than on belief, he is not combating St. Thomas, but just doing a different job.

The Christian response to Jesus involves, therefore, three main factors: belief that he is the Christ, the Son of God; trust in his saving power; and, a love that responds to his love. Whether we use the term faith to designate the first alone, or the first and second together, is not a matter of doctrinal disagreement, but of diverse vocabularies. Whichever one we opt for, let us do it, not only with faith, but also with ardent love!

- Years ago, I set out to treat this matter at length, by a thesis comparing the Thomistic notion of faith with that of the New Testament. What amounted to the first chapter appeared as a book entitled Faith in the Synoptic Gospels (University of Notre Dame Press, 1961), but I have never been able to go back and complete the project. ↩

Thank you for this article. Your point is well made and an encouragement. David Stern in his Complete Jewish Bible (CJB) makes the same point and translates pistis as trust – in one footnote he cites Buber who makes the same distinction as you have pointing out that the Hebrew emunah carries the sense of trusting that you talk about. Reading Hebrews 11 in the CJB with Trust substituted for Faith makes it a passage about living rather than a ‘heady’ assent of the faith of the ancients.

Thank you for your insight. I will keep this article for reflection.

I have had a hard time dealing with “Love” , and I think that perhaps this all is a part of problem, That my understanding of these three words is too shallow.

Thanks again,

LM