Though there has yet to be published a history of the formation of priests, the historic concern for good priests assumes that the Church has needed, and continues to need, effective seminaries and programs of formation

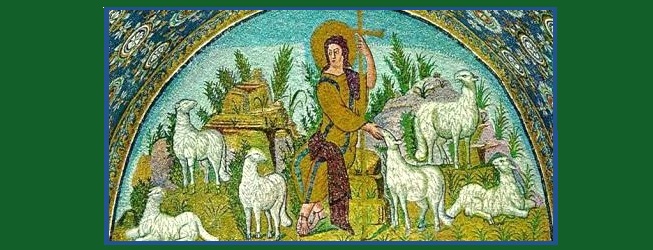

Christ, the Good Shepherd, mosaic at entrance to the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, 430 AD.

Introduction

There is little in common, at least in the perception of the American people, and perhaps justifiably so, between Capt. Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, and Capt. Francesco Schettino. Both were captains of a ship: The first, captain of an airship, now famously knows as U.S. Airways flight No, 1549, and the latter, a captain of a sea-going ship, now well known in the international news as the Coast Concordia. Both vessels and their well-trained captains experienced disasters in the water. In an heroic and dangerous feat, Captain Sullenberger had to unexpectedly land his passenger laden airship into the Hudson River on January 15, 2009. Only 728 days later, on January 13, 2012, in an unnecessary and intentionally dangerous move, Captain Schettino diverted his passenger laden cruise ship into perilously shallow waters near the shores of the Isola Giglia, just off the Italian Tuscan coast; in doing so he created his own disaster, the major details of which are already quite well known.

All the world watched as every one of the passengers from flight #1549 were rescued from the Hudson River. The captain of this airship remained on board until he was sure all of his charges and his crew were safe. Then, and only then, did he abandon the sinking airplane. The captain of the cruise ship, it has been alleged and widely reported, apparently abandoned his passengers and his boat almost at the first sight of danger. In mid-September, the ship was finally righted and sent on its way to the scrapyard. But tragically, 30 passengers on the Costa Concordia lost their lives, and two passengers are still missing. The captain of the Costa Concordia had apparently abandoned ship and, in an act of blatant self-preservation fled, as the gravity of the damage became ever more apparent. They are now famous, the recorded conversations from Captain Schettino’s superiors on dry land, commanding him to return to his ship; insistent commands. that fell on deaf ears. Both men can be referred to as captains of their respective “ships”, but that might be the singular trait the two have in common.

In a captivating way, there may be an analogy here. These two captains were called to be shepherds for the flocks entrusted to their care, not unlike priests who are called to be shepherds for the flocks that the Church entrusts to their pastoral care. Jesus makes a clear distinction between a good and an evil shepherd, the difference between one who will lay down his life for his sheep, and one who sees a wolf coming and runs away (Jn. 10:11-15).

All through the ages, the Church has given testimony to the need for good priests. Good priests presume solid preparation–that is, responsible, rigorous and competent formation. In the paragraphs that follow, we will examine some of the writings of significant persons in the history of the Church regarding the priesthood. Though there has yet to be published a history of the formation of priests, the historic concern for good priests assumes that the Church has needed, and continues to need, effective seminaries and programs of formation.

The priests of the Church have answered God’s call to care for his flock. The church, throughout history, has provided for those who have answered the call, programs of formation to prepare them to be good shepherds, stewards who genuinely care for their flocks. We hope to offer historical evidence here of the Church’s consistently (and justifiably) high expectations for priestly formation. In order to be faithful disciples, future priests need to be screened, molded, and prepared for such a graced, if pressing, and sometimes daunting, task. This is true in the Church universal, and is so as well in the Roman Catholic Church in the United States of America, especially in light of the recent challenges it has experienced, and of which much has been made in the media.

Persistent Priority

The Church has continually, if unevenly, been concerned with priestly preparation. Prospects for the priesthood enter the seminary, (from the Latin for “seed”), in order that the seeds of a vocation that only God can sow, might be nourished to come to full fruition as the Sower has intended.

In seminary formation, men are called to be formed, molded, and trained that they might be good shepherds. At times, formation initiatives have been very successful, as in the reforms called for by St. Charles Borromeo, and others, in response to the Protestant Reformation, and the concerns of the Council of Trent. Unfortunately, as history has shown, not all of those who have been trained to be so have, in fact, been “good shepherds.”

At times, seminary formation has fallen short of its lofty goals. Blessed Antonio Rosmini-Serbati (1797-1855) was critical of priestly preparation in his day, especially “in the seminaries where the candidates were educated by ‘petty men’ from ‘petty books’ and where ‘knowledge and sanctity’ were separated.” 1 In some instances, history has shown, those who have been well trained have not behaved as they had been taught. An instance may be found in a sermon by St. Augustine who employs a text from the book of the prophet Ezekiel in which he excoriates some selfish priests of his day, in the same manner the prophet criticized the leaders of his day, who were concerned solely with feeding themselves rather than the sheep. 2

Priestly Formation Today

As it has been in the past, the formation (and continuing formation) of priests remains a grave responsibility and a high priority for the American Catholic bishops who authored and who now implement the fifth edition of their “Program for Priestly Formation” (PPF). 3 That it has been continually revised betrays a sense of constant vigilance that it might address the changing needs and demands of preparing future ministers. This document “stems from its reliance on John Paul II’s Post-Synodal Exhortation, Pastores dabo vobis.” 4 Besides this exhortation, this fifth edition (of the PPF), has been informed by previous documents and sources which address the priesthood and seminary formation, including the recent seminary visitations with episcopal oversight mandated by John Paul II. 5

One of the prominent ways that Almighty God has been present to his people throughout the Judaeo-Christian tradition is through the provision of leaders. From Abraham and Moses, down to the present day successors of the Apostles, the Lord has given his people direction and guidance. In providing leaders, to this day, Jesus has kept his promise to be with his Church always. Through his grace, almighty God has seen fit to continue this gift of divine leadership through the Sacrament of Holy Orders. From Apostolic times to the present, through the invocation of the Holy Spirit, and by the episcopal “laying on of hands,” by the anointing with Holy Chrism, and with the support and the prayers of the faithful, men who have been prepared and are deemed worthy, become God’s gift of leadership for the Church. In Holy Orders, the priest receives a differentiation, a sacramental specification of his baptism, for particular service to the Church in Persona Christi. This gift, from the beginning of the Church to the present, has presumed discernment, preparation, formation and episcopal approbation of a candidate before he is received into the priesthood.

The Four Pillars

The four unique pillars of formation, which John Paul II outlines in Pastores dabo vobis are, of course, to be integrated in the life of each candidate. Those pillars include: Pastoral Formation—whose aim is to see that the priest’s ministerial activity, in imitation of Jesus, is carried out with grace and charity, i.e. the priest’s call is to discern, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, people’s real needs, and to meet them, as he is able, in a most suitable manner; 6 Intellectual Formation—intended to enable the priest, through a long esteemed adherence in the Church to the marriage of faith and reason, to be a teacher of truth; he is to reveal Jesus to others, the real face of God, in the ministry of the word and to give an account for their hope in Jesus, and to appreciate the genuine richness of authentic Church Tradition; 7 Spiritual Formation—addresses the ontological and psychological bond between Jesus and the priest. Prayer constitutes a sacramental and moral bond between Jesus and his minster. The proper spiritual life presumes meditation before and, after pastoral activity; it presumes a full prayer life drawing upon the rich spiritual tradition and forms of prayer in the Church, primarily of course, the Eucharist, and it assumes a personal encounter with the Trinity, from whom all graces flow; 8 Human Formation—which, according to Pope John Paul II, has a sort of “priority” among the pillars of formation—a priority that is not so much in gravity as in function. He refers to the human dimension of the minister as a sort of “bridge” to other persons, and one that has to be firmly in place for ministry in the name of Jesus to be effective. 9 This pillar insists on no small modicum of human sensitivity on the part of the priest. In other words, the priest, the good shepherd, must be able to compassionately respond to the hopes and expectations, the burdens, sufferings and joys of his flock. The icon (window) through which he must look to see how this is done most effectively is the most genuine expression of what it means to be human, Jesus, the one whom the priest is to imitate in all he says and does. 10

In compliance with the PPF, American seminaries have in place rigorous, demanding and responsible programs and activities affecting and effecting all four pillars. These include, but are not limited to careful and professional discernment and admission programs, personal external and internal (spiritual) advisors for each seminarian, a comprehensive pastoral works program with oversight and integrated reflection, an intellectually demanding course of studies, regularly scheduled conferences on formation issues, mandatory spiritual exercises, peer evaluations and regularly scheduled evaluations of each seminarian by the entire seminary faculty. All of these exercises are intended to provide for future priests opportunities to mold themselves as shepherds modeled on The Good Shepherd, Jesus Christ, in whose name they will one day care for his flock, the Church.

Through the Ages

Let us now turn to see how the expectations of priests (and, thus, of their formation), have generally been consistent and demanding throughout Christian history. In this essay, we intend to reflect upon the demands and obligations that the Church has rightly expected of its priests in years past. These expectations, of course, could never be met without presuming the importance of, and having in place, competent programs of priestly formation.

As early as the sub-apostolic era, St. Clement of Rome (d. ca. 101), wrote of the special dignity of priests as leaders of the worshipping community. Clement, a successor of St. Peter, wrote a letter to the Christian community of Corinth which was then experiencing a schism. Some members of the community had questioned the authority of the Corinthian priests. He wrote urging humility and obedience, and reminding them that the priesthood is a source of unity. Clement wrote that the Lord . . .

…commanded that the sacrificial offerings and liturgical rites be performed not in a random or haphazard way, but according to set times and hours. In his superior plan he set forth both where and through whom he wished them to be performed, so that everything done in a holy way and according to his good pleasure might be acceptable to his will. Thus those who make their sacrificial offerings at the arranged times are acceptable and blessed. And since they follow the ordinances of the master, they commit no sin. For special liturgical rites have been assigned to the high priest, and a special place has been designated for the regulars priests, and special ministries are established for the Levites. 11

Not long after Clement, St. Ignatius of Antioch (ca. 40-115) around 110 AD, while imprisoned in Rome and awaiting martyrdom, wrote to the Ephesians encouraging unity and harmony in the Church. For Ignatius, one key to church harmony is to recognize and obey the authority of the bishops and priests who are called to model the virtuous life. Among other things, their formation must prepare them to be model shepherds – to avoid the vainglories of this passing life. He writes:

For this reason, the Lord received perfumed ointment on his head, that he might breathe immortality into the church. Do not be anointed with the stench of the teaching of the ruler of this age, lest he take you captive from the life set before you. Why do we all not become wise by receiving the knowledge of God, which is Jesus Christ? Why do we foolishly perish, remaining ignorant of the gracious gift the Lord has truly sent? 12

St. Polycarp (ca. 69-155) died a martyr at Symnra. About the year 110, writing to the Christian community at Philippi, he shows concern that priests live virtuous lives. He criticizes Valens, a priest who, with his wife, had sinned. Polycarp assumes that a commitment to selflessness must be foundational in the preparation for, and the life of, a priest. Polycarp writes:

The presbyters should also be compassionate, merciful to all, turning back those who have gone astray, caring for all who are sick, not neglecting the widow, the orphan, or the poor, but always taking thought of what is good before both God and others, abstaining from all anger, prejudice, and unfair judgment, avoiding all love of money, not quick to believe a rumor against anyone, not severe in judgment, knowing that we are all in debt because of sin. 13

St. John Chrysostom (347-407) authored The Six Books on the Priesthood between the years 380-390, a work structured as a dialogue between himself and a colleague named Basil. He seems to presume that in aspiring to the priesthood, candidates must rid themselves of any hint of self promotion or ambition. St. John writes:

There are many other qualities, Basil, in addition to those I have mentioned which a priest ought to have, and which I lack. And the first of all is that he must purify his soul entirely of ambition for the office. For if he is strongly attracted to this office, when he gets it, he will add fuel to the fire and, being mastered by ambition, he will tolerate all kinds of evil to secure his hold upon it, even resorting to flattery, or submitting to mean or unworthy treatment, or spending lavishly.” (He continues…) I think a man must rid his mind of this ambition with all possible care and, not for a moment, be governed by it, in order that he may always act with freedom. For if he does not want to achieve fame in this position of authority, he will not dread its loss, either. (He then writes…) The priest’s shortcomings simply cannot be concealed. On the contrary, even the most trivial soon get known. (He continues…) The sins of ordinary men are committed in the dark, so to speak, and ruin only those who commit them. But when a man becomes famous and is known to many, his misdeeds inflict a common injury on all. 14

St. Ambrose (340-397), in his role as a mentor of Augustine, presumes his concern for proper priestly formation. Ambrose authored a number of works, among them a treatise on the priesthood (ca. 391). To those who would minister in the name of Jesus, he encourages humility and warns against self-promotion. He writes:

I think, then, that one should strive to win preferment, in the Church, only by good actions with a right aim; so that there may be no proud conceit, no idle carelessness, no shameful disposition of mind, no unseemly ambition. A plain simplicity of mind is enough for everything, and commends itself quite sufficiently. (He later continues:) But if anyone is disobedient to his bishop, and wishes to exalt and upraise himself, and to overshadow his bishop’s merits by a feigned appearance of learning or humility or mercy, he is wandering from the truth in his pride; for the rule of truth is, to do nothing to advance one’s own cause whereby another loses ground, nor to use whatever good one has to the disgrace or blame of another. 15

St. Gregory the Great (540-604), had been an abbot in Rome before being elected Pope in the year 590. Because of his concern for proper pastoral care of God’s flock, he penned thoughts on the responsibilities and obligations of those who shepherd God’s flock. Gregory, speaking of priests in this instance as “rulers,” noting that just because a “ruler” has surpassed another in power does not mean he has done so in merit as well. He writes:

The ruler should be, through humility, a companion of good livers, and through the zeal of righteousness, rigid against the vices of evil-doers; so that in nothing he prefer himself to the good, and yet, when the fault of the bad requires it, he be at once conscious of the power of his priority; to the end that, while among his subordinates who live well he waives his rank and accounts them as his equals, he may not fear to execute the laws of rectitude toward the perverse. (He later continues…) But commonly a ruler, from the very fact of his being pre-eminent over others, is puffed up with elation of thought, and while all things serve his need, while his commands are quickly executed after his desire, while all his subjects extol with praise what he has done well, but have no authority to speak against what he has done amiss, and while they commonly praise even what they ought to have reproved, his mind, seduced by what is offered in abundance from below is lifted above itself; and, while outwardly surrounded by unbounded favor, he loses his inward sense of truth; and, forgetful of himself, he scatters himself on the voices of other men, and believes himself to be such as outwardly he hears himself called rather than such as he ought inwardly to have judged himself to be. 16

Although St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) does not address the formation of priests directly, his commitment to the Order of Preachers is a tacit testimony to the importance of preparation for religious life. He does address, in an ancillary way, the need for virtuous leaders in his Commentary on the Gospel of John. Referring to chapter 2, wherein Jesus drives the moneychangers out of the temple, he interprets the passage mystically in three ways, warning priests to cherish, and handle carefully, the spiritual goods entrusted to their care:

First of all, the merchants signify those who sell or buy the things of the Church. These goods have been consecrated and authenticated by the teachings of the apostles and doctors, signified by the oxen . . . Therefore, those who presume to sell the spiritual goods of the Church, and the goods connected with them, are selling the teachings of the apostles, the blood of the martyrs, and the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Secondly, it happens that certain prelates, or heads of churches, sell these oxen, sheep, and doves, not overtly by simony, but covertly by negligence; that is, when they are so eager for, and occupied with temporal gain, that they neglect the spiritual welfare of their subjects. Thirdly, by the temple of God we can understand the spiritual soul, as it says: “The temple of God is holy, and that is what you are” (1 Cor 3:17). Thus, a man sells oxen, sheep, and doves in the temple when he harbors bestial movements in his soul, for which he sells himself to the devil. 17

St. Catherine of Siena (1347-1389), a Doctor of the Church, was not unfamiliar with ecclesiastical politics. She understood how attraction to the fleeting promises of this world could distract a priest from his vocation. In her famous “Dialogue,” she discusses with God the priest’s call to purity. Priests are reminded that even if they had given their bodies to be burned, they could never repay the Almighty for the grace and blessing they have received, a dignity, as God describes it, beyond which cannot be imagined this side of the Kingdom. St. Catherine writes of the priests, the words coming to her as if from the mouth of God:

Just as these ministers want the chalice in which they offer this sacrifice to be pure, so I demand that they themselves be clean. And I want them to keep their bodies as instrument of the soul, in perfect purity. I do not want them feeding and wallowing in the mire of impurity, not bloated in pride in their hankering after high office, not cruel to themselves and their neighbors—for they cannot abuse themselves without abusing their neighbors. If they abuse themselves by sinning, they are abusing the souls of their neighbors, for they are not giving them an example of good living, nor are they concerned about rescuing souls from the devil’s hands, nor about administering to them the body and blood of my only-begotten Son, and myself, the true Light in the other sacraments of holy Church. So by abusing them, they are abusing others. I want them to be generous, not avariciously selling the grace of my Holy Spirit to feed their own greed. 18

Jean Jacques Olier (1608-1657) recognized the need for solid seminary formation if the Church was to be provided with good, holy, and adequately prepared ministers. To that end, he founded the Sulpicians, a community of diocesan priests guiding, teaching, and supporting future priests. Jean Jaques Olier advocated for priests a simple lifestyle based on a selfless devotion to God. His fellow Sulpicians carry on formational work to this day. In his Introduction to the Christian Life and Virtues, we find the following:

(For priests) There will be no lack of (selfless) opportunities in this life, for he must suffer: first, the attacks of the world through scorn, calumny, and persecution; second, the violent onslaughts of the flesh in its uprisings and revolts; third, the battle with the devil in the temptations he sends us; finally the ordeals from God through dryness, desolation, abandonment, and other interior difficulties, which he inflicts on him in order to initiate him into the perfect crucifixion of the faith. 19

Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890) was an Anglican priest become Catholic priest. In his time as an Anglican and a don at Oxford, he initiated, with others, the Tractarian and subsequent Oxford Movements which attempted to restore the Church of England to its traditional principles. He was a voluminous writer, reflecting often on the priesthood. He insists on the dual nature of the priesthood: an admixture of the human and the divine. He writes:

And yet, my brethren, so it is, he has sent forth for the ministry of reconciliation, not Angels, but men; he has sent forth your brethren to you, not beings of some unknown nature and some strange blood; but of your own bone and your own flesh, to preach to you. “Ye Men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven. (He continues… ) . . . for it is your brethren he has appointed and none else—sons of Adam, sons of your nature, the same by nature, differing only in grace—men like you, exposed to temptations, to the same temptations, to warfare within and without; with the same three deadly enemies—the world, the flesh, and the devil; with the same human, the same wayward heart: differing only as the power of God has changed and rules it. So it is; we are not Angels from Heaven that speak to you, but men, whom grace, and grace alone, has made to differ from you. 20

Blessed Pope John Paul II, it is well known, held the priesthood in general, and his own priesthood, near and dear to his heart. There is presently a whole generation of seminarians who have recently completed, or are in the process of completing, their seminary studies, who credit their vocational calling to Blessed John Paul II, and have often been referred to as “John Paul II Priests.” He has written much on the subject of the priesthood and the importance of proper formation. Perhaps, the following might be a fitting conclusion as the Pope writes of the gravity and the necessity of a solid seminary foundation:

In the Church and on behalf of the Church, priests are a sacramental representation of Jesus Christ – the head and shepherd – authoritatively proclaiming his word, repeating his acts of forgiveness and his offer of salvation – particularly in baptism, penance and the Eucharist, showing his loving concern to the point of a total gift of self for the flock, which they gather into unity and lead to the Father through Christ and in the Spirit. In a word, priests exist and act in order to proclaim the Gospel to the world and to build up the Church in the name and person of Christ the head and shepherd. (He then continues…) Christ gives the dignity of a royal priesthood to the people he has made his own. From these, with a brother’s love, he chooses men to share his sacred ministry by the laying on of hands. He appointed them to renew in his name the sacrifice of redemption as they set before your family his paschal meal. He calls them to lead your holy people in love, nourish them by your word and strengthen them through the sacraments. Father, they are to give their lives in your service and for the salvation of your people as they strive to grow in the likeness of Christ and honor you by their courageous witness of faith and love.21

Conclusion

Both Captain Francesco Schettino and Captain Chesley Sullenberger were trained for their particular crafts. Both were called to be good shepherds. Maybe, the former had inadequate training in either knowledge or compassion; or, perhaps, his training was lacking in both. Or, perhaps, he was well-schooled in both, and paid little heed to what he had been taught. Throughout the history of the Church, it is fair to say, that most of the priests who have served as shepherds have reflected the values of Captain Sullenberger rather than those of Captain Schettino. This does not diminish the gravity of insisting upon competent and holy formation for future shepherds in the Church. Each priest is called, with his limitations and idiosyncrasies, as well as with his gifts and talents, infused by God’s grace, to be a good shepherd. As we have seen, throughout the ages, the Church continues to trust in God’s unconditional faithfulness to his promise to provide laborers for the harvest. But this call must be accompanied by the Church’s grave responsibility to cooperate in the action of God who calls men to formation. The Church creates and preserves the conditions in which the good seed, sown by God, can take root and, thus, bring forth abundant fruit, by providing competent, rigorous and demanding seminaries and programs of formation. The Church has historically fostered, prayed for, and guided those called forth to ordained ministry. And she continues to do so, by holding before them, in their seminary training, all the obligations and graces, the gravity and beauty, of Holy Orders in the in Persona Christi ministry of the priesthood to which they aspire.

- Quoted from Gallaro, George Dmitry. “The Seminary: A brief history of the place of formation.” The Priest. October, 2010, vol. 66, no. 10. pp. 36-38, 40, 52. Fr. Gallaro writes: “The Italian Blessed Antonio Rosmini-Serbati (1797-1855), in the second chapter of his work, The Five Wounds of Christ, severely criticizes the insufficient education of clergy. He continues to quote Rosmini–Serbati regarding the seminary: “The purpose is not simply to form good human beings, but Christians and priest enlightened and sanctified in Christ.” p. 40. ↩

- See Sermon 46 in SERMONS II, on the Old Testament. The Works of St. Augustine (A Translation for the 21st Century), Hill, Edmund, O.P., trans. and notes. Brooklyn, N.Y.: New City Press, 1990. pp. 263-270. ↩

- Program for Priestly Formation (fifth edition), Washington, D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2006. Copyright USCCB, Washington, D.C.. ↩

- Pope John Paul II. Pastores dabo vobis (“I Will Give You Shepherds: On the Formation of Priests in the Circumstances of the Present Day). Copyright Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1992. ↩

- “Report on (the) Vatican Visitation of U. S. Seminaries.” (Report published on Dec. 15, 2008 by the Congregation for Catholic Education). ORIGINS (CNS Documentary Service). Vol. 38, no. 33, January 29, 2009, pp. 520-529. ↩

- See: PDV #57-59. ↩

- See: PDV #51-56. ↩

- See: PDV #45-50. ↩

- This is somewhat parallel to Marshall McLuhan’s conviction that often “the medium is the message,” found in: McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1964. ↩

- See: PDV #43-44. ↩

- Clement of Rome. “Letter to the Corinthians.” Ed. and trans. Bart D. Ehrman. Loeb Classic Library. In The Apostolic Fathers I (LCL 24). Cambridge MA.: Harvard University Press, par. 40, pg. 107. “Since these matters have been clarified for us in advance and we have gazed into the depths of divine knowledge, we should do everything the Master has commanded us to perform in an orderly way and at appointed times.” ↩

- Ignatius of Antioch. “Letter to the Ephesians”. Ed and trans. Bart D. Ehrman. Loeb Classic Library. In The Apostolic Fathers I (LCL 24). Cambridge MA.: Harvard University Press, par. 17, pg. 237. ↩

- St. Polycarp of Smynra. “To the Philippians.” Ed. and trans. Bart D. Ehrman. Loeb Classic Library. In The Apostolic Fathers I (LCL 24). Cambridge MA.: Harvard University Press, par. 3, pg. 339, 341. ↩

- St. John Chrysostom. On the Priesthood. Trans. and Intro. Graham Neville. Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Press, 2002, pp. 80, 81. ↩

- St. Ambrose. Three Books on the Duties of the Clergy. The Principal Works of St. Ambrose. Eds. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace.Trans. Rev. H. de Romestin. Vol. 10. Peabody, MA.: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 1999. Book II, Chap. 24, pp. 61-62. ↩

- St. Gregory the Great. The Book of Pastoral Rule. Trans., Intro., notes and indices, Rev. James Barmby. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Leo the Great, Gregory the Great). Eds. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Peabody, MA.: Hendrickson Publishers, 1999. Second Series, Vol. 12. Part II. Ch.6, pg. 14. ↩

- St. Thomas Aquinas. Commentary on the Gospel of John. Trans. James A Weisheipl, O.P. Albany, N.Y.: Magi Books, Part I, Chapter 2, Lecture 1 (# 383). http://dhspriory.org/Thomas/SSJohn.htm ↩

- Catherine of Siena. The Dialogue. Trans. and intro., Suzanne Noffke, O.P. Classics of Western Spirituality Series. Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1980. (The Mystic Body of Holy Church, par. 113-114), pg. 213. ↩

- From Introduction to the Christian Life and Virtues, ed. William Thompson. Bérulle and the French School. trans. Lowell M. Glendon. Classics of Western Spirituality Series copyright, 1989, 244-247. As cited in On the Priesthood: Classic and Contemporary Texts, ed. Matthew Levering. Lanham, MD.: Rowman and Littlefield, Pub., 2003, Ch. 12, pg. 99. ↩

- Newman, John Henry Cardinal. Discourses to Mixed Congregations. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1899. Discourse III: “Men, not Angels, the Priests of the Gospel,” pp. 44-45. ↩

- Pope John Paul II. Pastores dabo vobis (“I Will Give You Shepherds: On the Formation of Priests in the Circumstances of the Present Day”). Copyright Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1992. Chapter II, par. 15 ff. ↩

As a lay man, I am particularly sensitive to the essential ecclesial communion that the Church sees uniting priest and lay people in their respective vocations. Describing the priestly ministry of governance, John Paul II wrote: “Above all it is necessary that he be able to teach and support the laity in their vocation to be present in and to transform the world with the light of the Gospel, by recognizing this task of theirs and showing respect for it.” (Pastores Dabo Vobis #59)

I find the lay vocation itself, with its implicit call to holiness, to “be present in and to transform the world with the light of the Gospel” is not well recognized or appreciated by priests or by laity. And if the Christian maturity of the laity is not a priority of the clergy, how are the laity to be directed toward it, or even cognizant of it? True priestly servanthood and fatherhood is needed, that the laity be rightly nourished, taught and led to the fulfillment and perfection of their vocation, and that the whole world might through them hear of and see the living Gospel of the Lord.

HPR recently published an excellent article on this very point, “The ‘Munus Regendi’ of the Priest and the Vocation of the Laity,” by (now Fr.) Gaurav Shroff. He included in his conclusion:

“This brief survey of Magisterial teaching on the munus regendi underscores that the priesthood as a whole, but especially in its exercise of the office of governance, is exercised with the full flowering of the vocation of the laity in mind. The goal of the priesthood is a mature and well-formed laity that embraces its own vocation. The formation of the laity, thus, is the unifying aim of pastoral governance, one that ought to be among the top priorities of a diocese, according to Pope John Paul II (cf., Christifideles Laici §57).”

This vision is, in my thought, absolutely crucial to the formation of a priest. This must be in his heart, a motivating force in his pastoral governance and a foundational concern in his preaching and his prayer. The father seeks to see his spiritual children come to full maturity in Christ, to the glory of God. Without this vision, we too easily see example after example of parishes of grown men and women still far short of Christian maturity, with only an institutional bond and not a living one with mother Church. We see grown men and women well sacramentalized but not catechized, attending Mass but not living the holy Liturgy in the secular world with the wholeness their lives, contributing merely to the maintenance of the church but not living members alive to the mission of the Church.

Paul VI said it so well, the Church exists to evangelize. That mission requires a mature laity, which requires well-formed priests with hearts on fire for the Gospel and its mission to the world. He wrote:

“Priests therefore, as educators in the faith, must see to it either by themselves or through others that the faithful are led individually in the Holy Spirit to a development of their own vocation according to the Gospel, to a sincere and practical charity, and to that freedom with which Christ has made us free. Ceremonies however beautiful, or associations however flourishing, will be of little value if they are not directed toward the education of men to Christian maturity.” (Paul VI, Presbyterorum Ordinis §6).

These concerns were with me as I wrote the article recently published in HPR, “What Happens to a Church When the Members Won’t Grow Up?” I am grateful for this article on the formation of priests – a subject of great general importance for the Church, and of particular relevance to the matter of my article.

Recently I wrote an email responding to a “John Paul II” priest’s homily. I asked him some questions about assumptions he made in his Sunday homily about the human experience of suffering people. His email response to me did not address my questions, but assured me of his prayers for me. Wow! Herein lies a serious problem that probably cannot be dealt with just in formation.

The priest as Gregory the Great indicated is a ruler. The self concept of a ruler makes it very difficult if not impossible to practice all the great virtues Gregory the Great and the many other saints mentioned in the article encourage in the priest.

How do people encounter a ruler? In the case of the priest when he speaks his word is taken as law unless he has broken down that subject ruler relationship. Francis, Bishop of Rome, is doing some historically significant things to take away the symbols of autocratic leadership and become more like Christ in his actions and words. Hopefully this will lead to a change in the way Catholics encounter their priests.