… what if God, who also wills to perfect his own mercy, made death itself a means by which we reach him? What if something crushed, something broken, became at the same time a path to life?

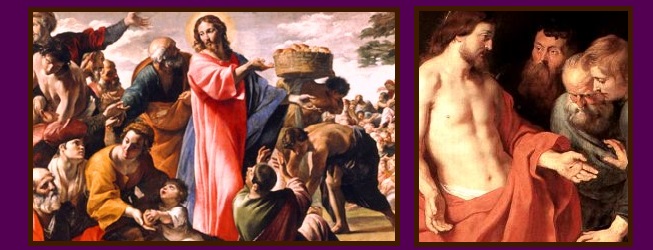

The multiplication of loaves and fishes. Christ shows his wounds to the Apostles.

In the Gospel of John we hear Jesus make an intriguing, but somewhat mystifying, promise: ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, he who believes in me will also do the works that I do; and greater works than these will he do…’ (14:12). I’ve always wondered why I haven’t heard more commentary on this passage. After all, the works that Jesus did, to say the least, were rather impressive—especially that business of raising the dead. His promise, though, is that those who believe in him are to do, not only the same, but greater. Healing the blind and the lame, raising the dead—these works, apparently, are supposed to be common provenance. Since we know that physical infirmity is a relic of original sin and, therefore, in the gospels an image of death; and, furthermore, since we are aware that as a Church we are embroiled in a combat with the culture of death; then obviously the source and nature of this life-giving power should be of interest to us.

According to Jesus’ words, as found in John’s Gospel, his works will be done by those who believe in him. This might indicate that any professing Christian is promised the power of Christ’s works. The act of belief, however, is not understood so broadly in John’s Gospel. In John, belief is not merely intellectual assent—or, so it seems from a reading of John 6, where we find a sequence of thought focused on the connected ideas of belief and work.

After the miracle of the multiplication of loaves and fishes, those who witnessed that miracle pursue Jesus across the Sea of Galilee. When they find him, there begins a question and answer dialogue between Jesus and his pursuers. Almost immediately, the topic of work appears: Jesus, noting all the effort they put forth in following him so far, and knowing that they did so for the sake of plentiful food, warns them “not to labor for the food which perishes.” Consequently, the crowd wants to know for what they should work in order to please God. Jesus answers, “This is the work of God, that you believe in him whom he has sent”(29)—a response which anticipates, through its association of work and belief, John 14:12 (“he who believes in me will also do the works that I do”). In both verses, then, Jesus establishes a clear association: work = belief. It’s not a fuzzy, scented candle type of belief, though. It is specific: “believe in him whom he has sent.”

Jesus might have ended there, and everyone would have gone home as happy Protestants. However, he did not end there. Instead, he continued to narrow the nature of work, and the particular object of belief. The “one whom he has sent,” he adds, is “the bread of God …which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world” (33). Finally, in terms that Catholic apologists know to be very, very clear, Jesus insists on the necessity of eating this bread—bread which, he’s said, is him, himself. Reviewing the steps of the argument, then, we have this: work=belief in the Son = bread = eating bread = life.

The testimony of the Gospels is that Jesus was a worker. Indeed, he stirred the ire of the establishment for his refusal to stop working on the Sabbath. His justification for doing so was simple: “My father is working still, and I am working” (5, 17). According to his own testimony, then, his work is the Father’s work. The Father’s work, for its part, is the ancient one, the work of creation itself, of being fruitful and multiplying, of bringing light from dark.

The Father’s work is his work; and, returning to the promise of John 14, his work is our work. We are told to heal; we are told to teach; we are told to raise the dead. However, we can’t forget the chilling words of John 15: “apart from me you can do nothing” (5). Apart from Jesus, we go back to the void. No matter what powers of state, of arms, of finance; no matter what amount of good intentions we provide to the work—nothing done by our own power is going to add up to anything. As Jesus tells Nicodemus, in John 3, what is flesh is flesh. Considered strictly as a matter of logic, the mortal nature of man can beget only that which is mortal. Here, one might soberly nod and agree that “you’ve got to have Jesus in your life;” the distinct, corporal person, though, usually loses himself in vague resolutions. Christ, therefore, and his body on earth—the Church—has given us a particular, tangible means of: (1) connecting to Jesus; and, (2) of working. The Church calls this means “the liturgy”—specifically, as articulated in John 6, the liturgy (work) of his body, the Eucharist.

We return to Jesus’ warning that, disconnected from him, we accomplish nothing. This is one of those blatantly obvious facts of life that we generally fail to see—no matter how many times a day we might trip on it. Yesterday, I began making repairs to my screened porch. Last summer, I made extensive repairs to the same porch; as I did the summer before that; and, the summer before that. Time erodes all things, whether a screened porch, firm abs, or an empire. Truly, how does one create? How does one overcome the effects of time, the eroding influence of sin, the destruction of death? “If a man does not abide in me, he is cast forth as a branch and withers …”(15:6). We have no power over death, unless we attach ourselves to him who passed through it.

What Jesus told his pursuers about work, and bread, and life, is starting to come together, then. Man is everywhere confronted by the menacing visages of decay and death. Justice for mortal man determines that they are his end. Justice is an attribute of God himself, for the cosmos demonstrates that he holds all things in balance. Being an attribute of God, justice cannot be circumvented; and, so it remains that our end is death. But what if God, who also wills to perfect his own mercy, made death itself a means by which we reach him? What if something crushed, something broken, became at the same time a path to life?

The range of belief—at least, as discussed in the Gospel of John—is very specific. We are told we must believe in the One whom the Father sent—Bread—in order to have eternal life. There is no other way to achieve life except through connection to him, who passes through death. And, what part of us is to be so connected? Mind? Desire? Body? Are not all three, and not just an isolated one or two, the fullness of who each of us is? Our connection to him, accordingly, must be complete—mind, desire, and body.

This, then, is the Eucharist: the means by which our endeavors become real. So, is that why the catechism makes deliberate use of the word “work” when defining liturgy—work just in the sense of a human act? No, more than this. The Eucharist is work in the same sense that Jesus spoke of work after healing the cripple in John 5: “My Father is working still, and I am working.” He heals, he forgives, he converts: he works. Something that wasn’t there before is brought into being. Of course, it is! We enter the Liturgy of the Eucharist in order to assemble around an altar of sacrifice. We go in order to hear words of self-gift: this is My Body; this is My Blood. What point to any of this could there be, unless we ourselves are supposed to join ourselves to this action, to this sacrifice. He who became sin, who became the curse, takes the sins and curses carried by us all. He takes them where, by their nature, they must go: to death. And then, they must go: to resurrection—to life. The nature of what we do, and of what we are, isn’t changed. It is transformed. Jesus’s resurrected body is the same that was crucified, died, and was buried. The same; but different:

Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, “Peace be with you.”

When he had said this, he showed them his hands and his side.

Then, the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord.

The juxtaposition here is telling: after the greeting of peace, he shows his wounds. Mindful of everything the disciples might have been just contemplating and fearing, why does he immediately show his wounds? Why not cover them until the disciples are a bit more reassured, more comfortable with his presence? There was something about those wounds that was, itself, reassuring. They were wounds, but wounds transformed. The wounds told them that death itself could be a path to beauty.

Jesus understood the Eucharist as work. The Catechism understands it as such; as does the Second Vatican Council… So what has happened to the idea? Why is the greatest power that we hold, so widely misunderstood, neglected, ignored, abused. This is what we have to do: take our work and make it creative.

If we abide in the vine, it’s as though, whatever we do, is done by the hands of Christ—the same hands that were nailed to the cross, but also the same hands that neatly rolled up the head wraps at the time of the resurrection. While those hands, with their wounds, carry the marks of sin, they are yet transformed into a beauty—the kind of beauty, apparently, that was able to bring peace to a room of fearing disciples.

Recent Comments